In no other country do shareholders love dividends as much as in Australia. Here are 10 key facts on dividends and franking, including one concluding piece of trivia.

1. Over the long haul, dividends have generated about half of the total return – capital gains plus dividends – investors have earned from Australian shares.

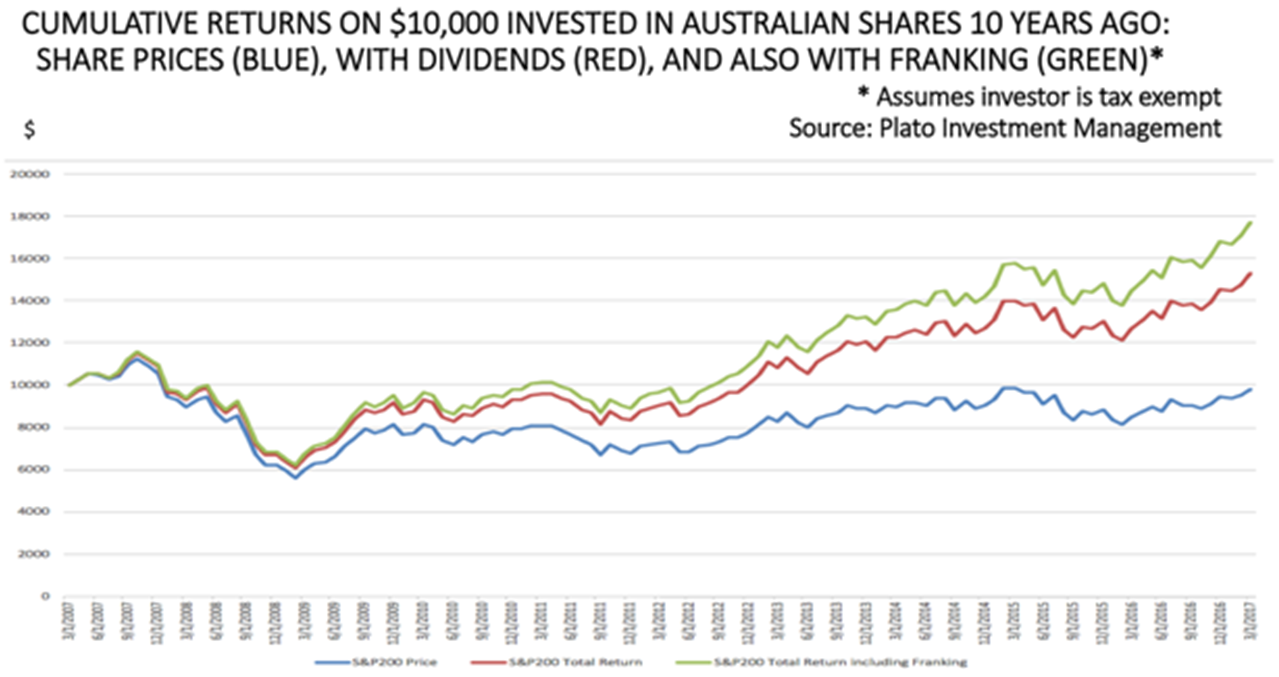

2. Dividends have more than pulled their weight in the last 10 years. Despite the collapse of share prices in 2008, the average investor who entered the share market a decade ago has achieved positive total returns, mainly due to the combination of good dividends and franking credits. The S&P/ASX200 Price Index (excluding dividends) is currently around 5,900, still well below its October 2007 level of 6,754.

The importance of dividends and franking credits to investor returns is illustrated in this chart from Don Hamson of Plato Investment Management. For many years, Plato has successfully run a managed fund specialising in franked dividends, and is currently launching a similar listed investment company.

3. Dividend franking particularly benefits investors on low tax rates. To a tax-free investor, including superannuation funds in pension mode, each dollar of a fully franked dividend is worth $1.43. That dollar of fully franked dividends would be worth $1.21 to an investor paying tax at 15%, including superannuation funds in accumulation mode. (From 1 July, tax at 15% will also apply to income paid into a retiree’s superannuation balance on assets exceeding $1.6 million).

4. For eight years, the average dividend yield on Australian shares has consistently been between 4% and 4.5% a year. With interest rates at low levels, and many investors on the hunt for yield, shares with good dividend prospects have had additional appeal.

5. Of course, it’s sustainable dividends that matter in stock selection. Among other things, investors need to avoid holding shares on which dividends are ‘paid’ from asset revaluations and capital raisings, and to be alert for ‘dividend traps’ (where the high dividend yield on a share may simply reflect the low share price because of an expected cut dividend).

6. Over the investment cycle, dividends are more stable than either company earnings or share prices. At times, however, dividends vary suddenly and unexpectedly, such as the dividend cuts announced by banks in 2009 and resource companies in 2016. The usual sequence in the investment cycle is for share prices to go through their cyclical turning point (maybe after one or more ‘false dawns’), followed by the turning points in company earnings and (later) in dividends.

7. On average, dividends account for about 80% of the after-tax earnings of Australian companies. That’s more than double the proportion paid in the US, where dividends are taxed twice and capital gains are taxed at lower rates than in Australia. Often in the US, total share buybacks exceed dividends. Even then, however, US companies finance a higher proportion of their future growth from retained earnings than Australian businesses.

8. Over the long haul, the average dividends per share in Australia has risen by about 7% a year – or slightly above the long-term increase we’ve experienced in nominal GDP. Looking ahead, trend growth in average dividend per share is likely to be a more modest 5% a year.

9. Dividend franking will lose some appeal from the recent legislation to cut the rate of company tax on businesses with revenues of less than $50 million.

10. Finally, let’s look at a dividend yield that shows this year’s dividend as a per cent of the share price an investor would have paid when purchasing the share many years ago. When the Commonwealth Bank was floated in 1991, its shares each cost $5.40. In the last 12 months, the dividend per share has been $4.21. Thus, the dividend yield is 5% on the current share price, but 78% when calculated on the share’s original cost. A zero-taxed investor would also have benefited by $1.80 a share in the past year from the franking credit, giving a dividend plus franking yield of 111% on the price many (patient) investors would have paid.

Don Stammer has been involved with investments since the early 1960s including senior executive positions in Deutsche Bank and ING. These days, in his semi-retirement, he’s an adviser to Altius Asset Management and Stanford Brown Financial Advisers and he contributes a fortnightly column on investments for The Australian. The views expressed in this article are his own.