Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney's Davos speech dramatically amplifies the political risk embedded in Australian housing policy and accelerates the timeline for when those chickens come home to roost.

His central thesis, that we are witnessing "a rupture, not a transition" in the global order, means the comfortable policy assumptions that have underpinned Australian household wealth accumulation for three decades are now exposed as contingent, not permanent. And for Australia as a middle power, the fiscal and strategic implications directly threaten the sustainability of generous housing subsidies.

The fiscal capacity problem

Carney explicitly called for middle powers to build strategic autonomy in energy, food, critical minerals, finance and supply chains, emphasising the need to rely not just on values but on strength. He noted Canada is doubling defence spending by decade's end.

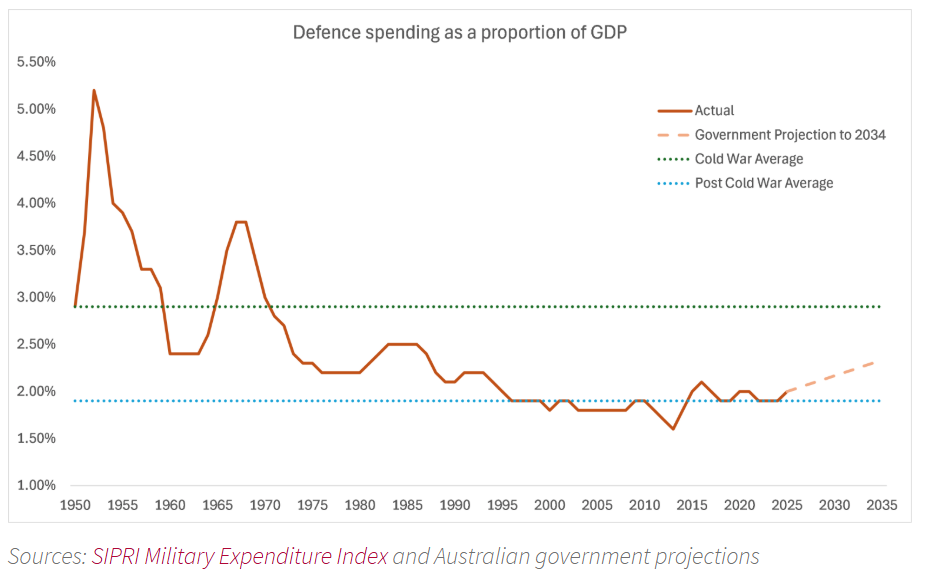

Australia is on a parallel track. Defence spending is projected to grow from $44.6 billion in 2026 to $56.2 billion by 2030—a compound annual growth rate of 5.9%. As a percentage of GDP, this rises from 2.05% currently to 2.34% by 2032-33 under current government plans, with the opposition Coalition committed to reaching 3% of GDP within a decade. The US is pushing allies toward 3.5% of GDP.

This is not optional. Carney's framing makes clear that in a world where great powers use economic integration as weapons and supply chains as vulnerabilities to exploit, middle powers that cannot feed, fuel, or defend themselves have few options.

Now overlay Australia's fiscal position: a budget deficit of $36.8 billion in 2025/26, net debt at 20.1% of GDP ($587.5 billion), and structural spending pressures from aged care and the NDIS. While the treasurer has reduced projected deficits, gross debt is expected to remain at $1.16 trillion through 2027-28, with savings not materially improving the balance sheet.

Here's the collision: Australia needs to find an additional $10-15 billion per year in defence spending over the next decade while managing structural deficits and rising debt. At the same time, it is foregoing an estimated $50-70 billion annually in CGT revenue by exempting principal residences from capital gains tax, and subsidising Age Pension eligibility for homeowners with millions of dollars in exempt housing wealth.

In Carney's framework, that arithmetic no longer adds up. When a middle power must build domestic resilience, invest in critical infrastructure, and double defence spending, subsidising tax-free capital accumulation in oversized family homes becomes a luxury it can't afford.

But why would subsidies actually end?

The political economy cuts both ways. Homeowners still outnumber renters electorally. Housing wealth effects support consumption and confidence. And governments facing economic uncertainty might hesitate to crystallise paper losses for millions of households.

The answer lies in relative priority, not absolute necessity, and in a fundamental shift in the electoral coalition that opposes housing subsidies.

Defence spending increases are non-negotiable treaty commitments and strategic imperatives. Aged care and NDIS are legally mandated programs. When fiscal space is finite, discretionary tax expenditures, which are what housing concessions are, structurally become the release valve. The question isn't whether housing subsidies are politically popular (they are), but whether they're defensible when the alternative is cutting defence capability or breaking international commitments. Carney's rupture framing shifts that trade-off from theoretical to immediate.

But there's a second, equally important dynamic: the electoral math on housing subsidies has already shifted, and most politicians haven't noticed yet. Gen Z and Millennials, who are locked out of homeownership, obviously oppose subsidies that inflate prices. But they're now joined by Gen X and Boomers with adult children who see the direct cost of these policies in their kids' lives. A 58-year-old homeowner in Western Sydney who owns their home outright may personally benefit from CGT exemptions, but when their 28-year-old daughter is paying $650/week in rent with no path to ownership, the political calculus changes.

This coalition, renters, prospective first-home buyers, and homeowners with children struggling to enter the market, now represents the majority in nearly all electorates except wealthy inner-city enclaves and retirement-heavy areas. The beneficiaries of maximum housing subsidies are increasingly concentrated in a narrow band: older homeowners in premium suburbs without children affected by affordability, and property investors. That's not a winning electoral coalition nationally, even if it's overrepresented in safe seats and marginal electorates that happen to be wealthy.

When you combine this shifted electoral math with fiscal necessity and strategic imperative, the political path to reform becomes clearer. A government can credibly argue: "We're not punishing homeowners; we're redirecting resources from untargeted subsidies that hurt your children toward defence spending that protects your grandchildren." That narrative threads the needle in a way that pure fiscal sustainability arguments never could.

The rupture framing amplifies this by adding urgency. It's not "we should reform housing subsidies eventually", it's "we must choose between subsidising $2 million tax-free homes for empty-nesters and funding the submarines that ensure our sovereignty."

The capital flow question

Carney emphasised that middle powers must pursue international diversification as both economic prudence and the material foundation for principled foreign policy, since countries earn the right to principle by reducing vulnerability to retaliation.

For Australia, this means reducing dependence on any single trade or capital partner. Recent research notes that while China remains Australia's largest trading partner, efforts have diversified trade relations with India, Japan, and ASEAN. But it also warns that reliance on foreign investment increases susceptibility to external shocks and that real estate-driven growth poses financial stability concerns.

Would fortress economics actually involve capital controls? The mechanism deserves scrutiny. Research on capital controls shows they can be effective during crises for preventing destabilising outflows, but they impose costs: reduced growth during expansions and implementation challenges.

The more plausible pathway is selective restriction rather than comprehensive controls. Australia has already implemented targeted foreign investment restrictions on residential property through FIRB. In a rupture environment, these would likely tighten further—not through capital controls per se, but through:

- Stricter FIRB approval criteria prioritising strategic sectors over residential property

- Tax disincentives for foreign residential investment (building on existing surcharges)

- Regulatory preference for capital flows into defence-related industries, critical minerals, and energy infrastructure

- Reduced tolerance for property speculation that doesn't build productive capacity

The effect is similar to controls without the implementation complexity: foreign capital inflows into residential property face higher barriers, while domestic capital is incentivised (through tax settings and regulatory signals) toward strategic sectors rather than housing speculation. A government mobilising investment for national resilience has little reason to maintain tax settings that channel household savings into ever-larger homes rather than productive infrastructure.

This is policy redirection, not financial autarky. But the directional pressure on housing demand is the same.

The intergenerational equity accelerant

Carney's thesis makes intergenerational equity, already a political flashpoint in Australian housing, an issue of national strategic importance, not just domestic fairness.

Younger Australians are, to put it mildly, noticing housing unaffordability, with record numbers abandoning major parties and housing policy as a primary driver. Australia is projected to fall 50,000 homes short of annual targets in 2026, with established house prices rising 9% in 2025. The generational wealth gap is widening.

In Carney's framework, this is not just a social policy problem, it's a strategic vulnerability. A middle power facing an uncertain, competitive international environment cannot afford a generation locked out of wealth accumulation and therefore less financially resilient to shocks, or declining social cohesion when a foundational element like shelter is unavailable to median households.

The strategic argument is strongest when focused narrowly: generational lockout weakens the institutional trust and financial resilience needed for national cohesion during a crisis. When young professionals see no path to housing security, they optimise for individual survival, emigrating to more affordable allied countries or withdrawing from civic participation. This matters because middle powers facing great power competition need maximum social solidarity and minimal brain drain.

Carney's language about middle powers needing to build something stronger and more just, with emphasis on reducing vulnerability, reads almost like a direct rebuke to current Australian housing policy settings. You cannot build national resilience on a foundation of intergenerational inequity, extreme household leverage, and fiscal subsidies that channel resources away from strategic priorities.

The Three Political Risk Amplifiers

Carney's speech doesn't just add to political risk; it acts as a catalyst that makes previously gradual pressures acute:

1. Fiscal urgency

What was a slow-burn sustainability problem (how long can we afford housing CGT exemptions?) becomes an immediate trade-off. Every dollar of foregone CGT revenue is now a dollar not spent on defence, critical infrastructure, or strategic autonomy. The NSW Government's submission arguing that the CGT discount on investment properties places pressure on house prices upward will now be joined by the Treasury arguing that all housing tax concessions are unaffordable in a rupture environment.

The fiscal math creates a forcing function: when defence spending must rise from 2.05% to 3% of GDP, that's roughly $25 billion annually in additional spending by 2030. Housing tax expenditures of $50-70 billion per year represent the single largest pool of discretionary fiscal capacity available without cutting essential services or raising broad-based taxes.

2. Policy legitimacy

Carney emphasised that when middle powers negotiate bilaterally with hegemons, they negotiate from weakness and accept what's offered. The same logic applies domestically: when a government negotiates with entrenched interests defending their subsidies, it negotiates from weakness unless it has a compelling national narrative.

Carney's rupture framing provides that narrative: "We can no longer afford policies designed for a stable, rules-based world that no longer exists." This makes previously politically untouchable reforms, partial inclusion of the home in the Age Pension assets test, CGT exemption caps, and aged care means-testing integration suddenly defensible as necessary for national security.

This isn't about whether such reforms are actually required for security in a technical sense. It's about whether a government can construct a politically sustainable narrative for unwinding popular subsidies. The rupture frame provides that narrative in a way that "fiscal sustainability" or "intergenerational equity" alone do not.

3. International precedent

Carney called for middle powers to form coalitions on a topic-by-topic basis. Could housing subsidy reform become one such topic?

The precedent for coordinated domestic tax policy reform is admittedly thin. The OECD's BEPS framework on corporate taxation shows it's possible, but housing subsidies are far more politically sensitive than corporate tax avoidance. Free-rider problems loom: each country might prefer others to reform while keeping its own subsidies to attract capital and talent.

But the politics shift if the reform is framed as a strategic necessity rather than economic optimisation. If Canada, Australia, and comparable middle powers face similar fiscal pressures, defence increases, aging populations, infrastructure needs, then near-simultaneous housing policy reforms become more politically feasible. Not because of formal coordination, but because each country can point to others facing identical constraints and making similar choices.

The fact that Mark Carney has signalled this shift makes near-term action more plausible. If Canada moves first on housing subsidy reform explicitly tied to defence funding, it provides political cover for Australia to follow. This isn't a 2028 treaty commitment, but rather a demonstration that such reforms are both possible and defensible.

The portfolio implication

For investors: the Carney thesis reinforces that Australian households holding $1.8 million in their home and $700,000 in super are now explicitly long two massive, correlated risks:

- Property market risk (double-digit volatility, concentration, and liquidity constraints)

- Policy rupture risk (fundamental reordering of national priorities in response to geopolitical change)

The scenarios previously modelled as edge cases, partial assets test inclusion, CGT exemption caps, aged care integration, are no longer speculative. They are probable policy responses to the fiscal and strategic imperatives Carney described. And because the rupture framing delegitimizes old assumptions, these reforms could happen faster and with less warning than traditional political cycles would suggest.

The correlation matters. In a scenario where housing subsidies are curtailed to fund defense:

- Property prices face downward pressure (reduced tax advantage)

- Household balance sheets weaken (lower home values, possible CGT on future gains)

- Retirement plans built on downsizing or equity release become less viable

- Aged care funding strategies assuming exempt housing wealth fail

This isn't two independent risks that might offset. It's a single regime shift that amplifies both simultaneously.

Ben Walsh is Principal Consultant at WealthVantage Partners.