Paying attention to the current settings of fiscal and monetary policy, as well as the prospects for inflation, gives a reasonable explanation of current market valuations. This allows investors to better understand how bonds, especially long bonds, might strategically act to temper disappointment when stockmarket expectations are elevated.

Context of fiscal and monetary stimulus

At present, global governments and central banks have set a highly stimulatory setting for equity markets, as a way of offsetting the depressing impact of the pandemic, both in terms of fiscal and monetary policy.

Let's check the context for each.

a) Fiscal policy

The Australian Government has increased spending substantially, with Federal net debt expected to grow to around 43% of gross domestic product (GDP), peaking in the period 2023-24. Large stimulus measures, such as JobKeeper, which will stay in place until March 2021, a programme that alone will cost around $90 billion.

In terms of US fiscal policy, there was the initial US$8.3 billion Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriation Act, a second US$3.4 billion stimulus package and two other packages of US$2.3 trillion and US$900 million. Currently, President Biden is seeking to provide another US$1.9 trillion of stimulus. Similar fiscal stimulation measures are in place in Europe.

These fiscal stimulus packages are about as large as they possibly could be.

b) Monetary policy

Domestic monetary policy has been eased to completely unprecedented levels, with the RBA expecting to leave rates low for the next three to four years. Bond buying aims to keep the three-year rate at 0.1%. Similar low rate commitments have been made in the US and Europe.

What does this context mean for equity valuations?

Fiscal stimulation is generally aimed at improving the growth at an economy, and the equity markets have come to a consensus view: the vaccine effectively builds a bridge from the current situation of high unemployment and low growth, to a higher level of economic growth and lower unemployment.

As this consensus view has gradually been adopted, a higher level of growth has gradually been built into the pricing of equities, especially the S&P500. One measure of the long-term valuation of the S&P500 is the Schiller PE, where price is divided by the average of 10 years of earnings, adjusted for inflation.

In the past, prior to all the monetary easing of the last decade, a good rule of thumb was to buy the S&P500 around levels of 5 on the Schiller PE and then to sell equities as the level exceeded 25. However, the Schiller PE is so elevated that the old range of 5 to 25 seems to have been skewed upwards to a new range between 15 and 35.

The current Schiller PE is at the top of this adjusted range. In addition, if the current stimulation is withdrawn, and interest rates revert to longer-term averages, then the Schiller PE could then adjust back towards the older range.

Will stretched valuations lead to volatility?

Given this elevation, markets should magnify even trivial issues, and possibly decline more than they would, in the absence of such an elevation. Some issues could inspire this decline by questioning the validity of the ‘bridge-building’ view of economic growth.

A list of the possible issues is:

Antitrust and technology: Regulation of the large technology companies in the US, especially regarding anti-trust regulation. This debate has been developing for some considerable period of time.

Pandemic variants: The efficacy of certain vaccines may come under increasing scrutiny, as variations of the pandemic become more apparent, and as those variants resist the existing suite of vaccines.

Default acceleration: Business defaults may begin to accelerate, much more than currently expected, once existing relief measures are eventually withdrawn.

Inflation rises: Recent increases in commodity prices are significant, and these have been largely absent over the last decade. The rise of commodity prices might be more about the declining US dollar, but higher commodity prices tend to support higher inflation, all else being equal. If inflation does break out substantially, then rates will rise, meaning current equity valuations will be revised downwards.

Underestimation of virus impact: In general, markets may be underestimating the impact of the virus on the economy, and a recent series of jobless claims releases, where the market has underestimated the size of the jobless claim numbers, is indicative of a complacent attitude.

This is not an exhaustive list and I am not maintaining that any of these triggers will occur in the short term. Rather, the strategic point here is that current valuations should elevate volatility due to stretched valuations.

Role of bonds to cushion equity volatility

The typical institutional portfolio includes a dedicated allocation to long-dated bonds. However, the low level of bond yields has presented the idea that the defensive power of bonds might have collapsed.

To explain, if bonds are already low in yield, then expecting large declines, possibly in reaction to an equity market decline, was seen as not feasible. Even put more simply, if 10-year rates are at 5%, then they can fall a lot, but if they are at 0.5%, then they can still fall, just a lot less.

However, following recent rises, long bond yields are now back to where they were just before the pandemic started. Among other things, this reflects optimism and the deflation of that optimism should enable yields to fall substantially again from current levels in the event of a decline in equity pricing.

For the sceptics out there, I am not saying that bond yields have peaked and that they will not rise for years. Rather, bond yields now reflect the optimism in equity markets, and that optimism is increasingly ephemeral, given the elevation in the Schiller PE.

More importantly, and from a strategic perspective, bonds now provide a feasible equity volatility cushion. If equity pricing comes under pressure, a small retail portfolio should benefit from what every institutional portfolio has: a long bond allocation.

If you have a long bond with a 10-year modified duration, then for every 100 basis points that the bond moves in yield, the capital price of bond will vary by roughly 10%. Equally, if the modified duration is 20 years, then the impact on bond prices if yields decline 1%, is roughly 20%.

Of course, the reverse is true as well.

An example of how long bonds helped the portfolio last year

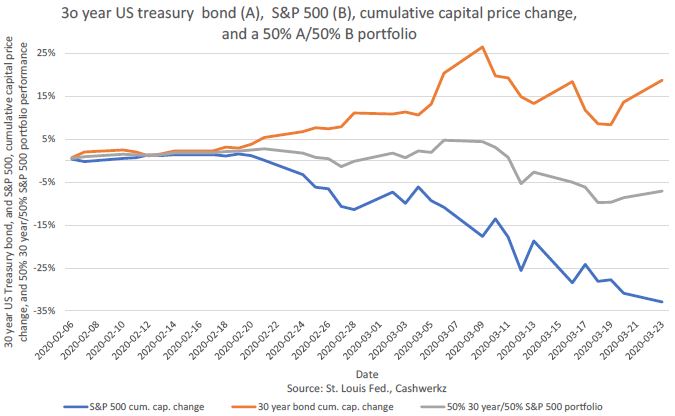

Now, if equity pricing declined by, say 20%, it is likely that long bond yields will decline in yield, which means that capital prices will rise. A decline of 0.5% in the long bond yield might a reasonable estimate of how far a bond yield might decline in a 20% equity decline, although estimates of bond yield declines in situations of economic stress are usually unreliable.

In this situation, where the long bond declines by 0.5%, the capital price on the 10-year modified duration bond would rise 5%. It helps to partly offset, to cushion, the loss from equities to some extent.

The following chart indicates in the crisis period of February 2020, 30-year bonds went up strongly in price, as shown by the orange line, and that price increase assisted portfolios which were experiencing losses form equity positions. A 50/50 portfolio of 30-year US Treasury bonds and S&P500 equities would still experience losses but significantly less as shown by the grey line, relative to a portfolio without long bonds, as shown by the blue line.

Conclusion for your portfolio

Equity valuations are currently lofty, but long bond rates have now returned to where they were before the pandemic crisis of March 2020. Generally, this confluence of events means that while you hold equity in your portfolio, the bond market has recently provided an opportunity to cushion the volatility of equities, by buying longer dated bonds. If equities continue to rise, then you can focus on the overall growth in your portfolio.

Dr. Stephen J. Nash is a member of the FTSE Asia Pacific Fixed Income Index Advisory panel, the author of an extensive list of published journals, and an independent specialist partner of BondIncome, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Please consider financial advice for your personal circumstances.

For more articles and papers from BondIncome, please click here.