In Part 1 on business model disruption, I examined how the advertising and retailing world is changing, driven by new technologies and especially how much Facebook, Google and Amazon know about their clients.

Let’s look at the world’s largest consumer products company, Procter and Gamble. The goods they sell like Gillette, Olay, Pantene and many of their other products are in our daily lives. P&G is the largest television advertiser in the world, and this is a part of their business model. There are huge barriers to entry into television advertising and you can own a share of mind of consumers. Tide is the largest laundry detergent in the US. P&G needs to convince consumers that when they stain a shirt, Tide is the one that’s going to take the stain out, and that’s the role of traditional advertising.

Wonderful businesses for 50 years

When you walk into a Walmart store, there are 25 metres of an aisle with the Tide laundry detergents seen on television. It’s a massive visual of those products and it receives huge turnover for the supermarket. They win because they are getting the velocity, the advertising businesses get their advertising revenues, and P&G has a business with the most dominant brands in its categories in the US.

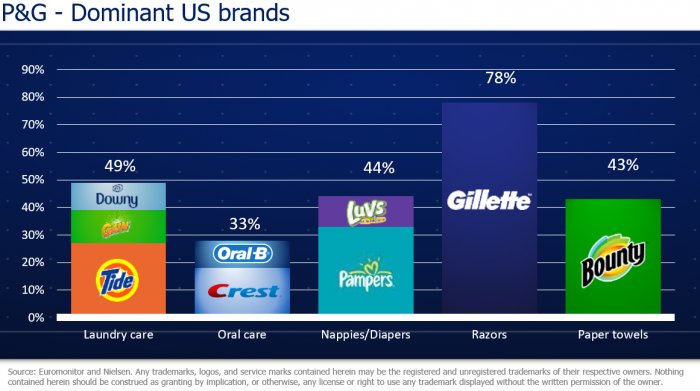

In laundry detergents, adding all P&G’s brands, they have 49% of the US market. In oral care, they’ve got 33%, but it’s a duopoly. The other is Colgate, and between the two, they have 80% of the market. We could go through nappies, razors, paper towels, shampoos and other things where dominant companies use traditional forms of advertising and traditional forms of retailing to create high market shares. These businesses have been wonderful businesses to invest in for the last 50 years. Think of Nestle and other big brand-owning companies over the world. And Magellan has owned a lot of these companies in the past as well.

Now let’s think about a weekly shop that Amazon’s Jeff Bezos has in mind using the Alexa digital assistant. It can order regular items that are running low, but whereas it knows you previously bought Tide washing detergent, Fairy dishwashing tablets and Charmin toilet paper, it can suggest Amazon products to replace these brands. The Alexa platform is already operating in the US. If you ask Alexa to order a battery for your torch, the only batteries it will offer you are Amazon-branded batteries.

It’s hugely disruptive when these new technologies affect the brand-owning companies. A company like P&G is not about to go bankrupt, but the future is much less rosy. Their rate of growth will dramatically slow down as they lose volume, and there will be more price competition because the home products will be sold at lower prices and at great quality.

A serious challenge to mean reversion

I’m a quality and value investor, and P&G on average over time has traded at around 20 times earnings. So when P&G trades at 15 times earnings or less, in the past I would have thought, “Well I know they’ve got dominant brands, I know their business model is robust” and I would probably have bought P&G and then patiently held it. I expected its multiple would probably go back to its long-term average, and I’d earn excess returns. If it was trading at 24 times earnings, I’d know it’s probably going to come back to 20 times earnings so I’m probably not going to own it at that point in time.

The mean reversion process of looking at past behaviour which meant buying at 15 times earnings as it is likely to trade at 20 times earnings in the future and deliver excess returns. Now, I seriously challenge whether that’s going to work into the future, even when investing in something that’s high quality with a robust business.

We’re talking about disrupting some of the world’s highest quality companies. I’d probably add something like a Bitcoin and other fintechs into the threats that banks need to be thinking about.

So what are some of the experts saying about what’s going on with big consumer companies?

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger on disruption

At the 2016 AGM of Berkshire Hathaway, there was a fascinating interaction between Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett:

Munger: “A lot of great businesses aren’t quite so great as they used to be. The packaged good business of the P&G and the company General Mills, they’re all weaker than they used to be at their peak, and the auto companies, I mean, when I think of the power of General Motors when I was young and what happened, they wiped out all the shareholders. I would not have predicted that. When I was young, General Motors loomed over the economy like a Colossus. It looked totally invincible. Torrents of cash, torrents of everything and it learned to hold down market share because they were afraid they’d be too monopolistic. Yes, the world changes and we can’t make the portfolio change every time something is a little less advantaged than it used to be.”

Buffett: “But you have to be alert, thinking all time to whether there’s been something that really changes the game in a big way and that’s not only true for American Express, that’s true for other things we own, including things we own 100% of. And we’ll be wrong sometimes. We’ll be right sometimes, we’ll be wrong sometimes, but we’ll be right sometimes too. But it’s not that we’re not cognisant of threats but assessing the probabilities of those threats being a minor problem or a major problem or a life-threatening problem. You know, it’s a tough game but that’s what makes our job interesting.”

These two are absolutely incredible. Warren’s just turned 87 and Charlie’s 93. I’d love to be doing this when I’m 87. Warren was saying that assessing the probabilities of these threats is key and you need to then ascertain whether the threat is minor, major or life-threatening, and I think that is really our job. It’s easy to get caught up with these changes but you have to think about the probability of some of these changes and over what time frame. A technology like a driverless car, which I think is a very high probability over a 10-15-year period, it’s going to have a life-threatening impact on a lot of automotive manufacturers. People will start sharing car fleets so they don’t need to own their own cars.

Portfolio positioning in the face of change

P&G will not go completely out of business but new technology will change the value of P&G. The stuff that’s starting to happen will have modest impact on a business like that, and I need to reflect that into the valuation.

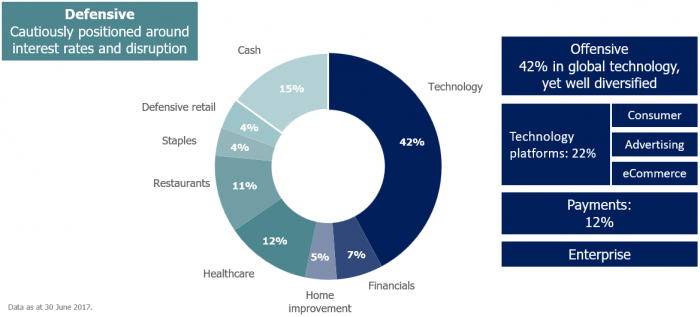

With technology, we’ll have more deflationary effects in the world. If I took a 10-15-year view, I expect a lower long-term interest rate view. Technologies such as AI, new forms of manufacturing, 3D printing, driverless cars – I won’t go through them all - could be massively disruptive to the inflation curve. In the next few years, we’ll probably have a headwind of rising interest rates, but in the long term, we could have interest rates coming down again. That’s exercising a lot of our thinking.

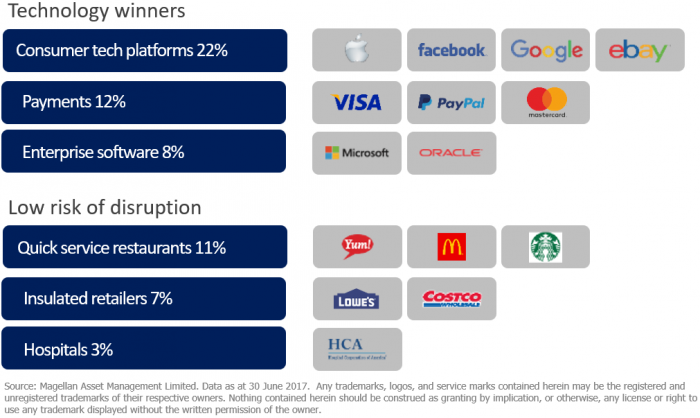

I’ll finish with a couple of slides showing how we have positioned the portfolio to meet these challenges, and the particular companies we believe are best-placed.

How are we positioned?

Navigating disruption

This is an edited version of a presentation by Hamish Douglass, CEO, CIO and Lead Portfolio Manager at Magellan Asset Management, at the Morningstar Individual Investor Conference 2017 on 6 October 2017. Graham Hand attended the event courtesy of Morningstar.