The recent $1 billion investment in the Commonwealth Bank (CBA) by the Texas based fund manager - Fisher Investments (Fisher) – suggests that US-based capital is beginning to move in anticipation of a substantial Trump directed quantitative easing (QE) program.

In my view, Fisher’s investment is not a strong vote of confidence in either the quality or value of CBA. Fisher manages over US$500 billion, so this is not necessarily a major position for the group. Rather, it is an investment that expresses concern for the outlook of the USD by large active US based investors. It is part of a significant hedging strategy, and it will be interesting to see how it plays out.

Speculating on the full range of reasons behind the investment by Fisher, the Australian Financial Review reported that: “Sources said Fisher was buying on behalf of clients who wanted to increase the exposure of their share portfolios beyond volatile markets in the United States”.

I would suggest that active US-based asset managers, their consultants, and advisors, are urgently reviewing their investment portfolios. With Trump unleashing a continuous tirade at the Chair (Jerome Powell) of the Federal Reserve (Fed), they have concluded that a QE policy will occur at some point.

Further, whilst a general rise in tariffs will lead to an elevated inflation rate, a direction to the Fed to decrease interest rates will result in “negative real rates” - where cash rates and bond yields are driven below inflation by the Fed. This can only occur if QE is undertaken as part of a coordinated monetary program that includes an aggressive reduction in US cash rates.

The confusing outlook – higher inflation but with lower interest rates – flows directly from a strategy of monetary policy interference by the Trump Administration.

Based on statements of both President Trump and Treasury Secretary Bessent, they have a probable target of 2.5% (cash rate), about 3% for ten-year Treasury bonds and 4% for 30-year Treasuries. At those levels, the Trump Administration may hold the US government’s interest bill to about 15% of US budget outlays. An uncomfortable level that is the upper limit of what is manageable.

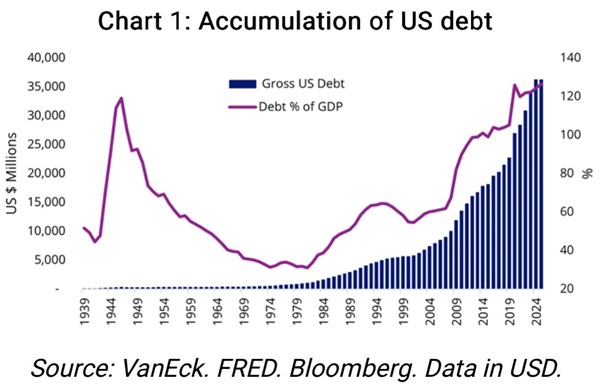

Considering all factors in the US fiscal outlook following the passing of Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill, the need to stabilise the US budget and debt is clear - especially with the US debt ceiling to be breached again in August. Both US government debt (110% of GDP) and its interest bill (rising above 3% of GDP) will be confronting for the bond market. Without central bank intervention, the bond market could falter, driving yields higher and bond prices lower.

Active managers must respond and a growing allocation to liquid non-USD assets comes into focus, particularly for US domiciled funds. Therefore, a tactical allocation towards AUD assets (inside an expanded non-USD allocation) is justified.

When targeting Australia, the choices are liquid AUS government bonds, corporate debt, and equities.

CBA, with no USD currency exposure, fits the bill perfectly. It is a pure AUD play and has a massive market capitalisation (about $300 billion). It is also the largest and best-performing bank in Australia, and one of its most valuable brands. Of note, unlike our major resource companies, neither its operations nor revenues will be affected by USD gyrations.

Obviously, this investment will unwind at some point in the future. But on the day, it created a rare liquidity event for Australian funds to sell down CBA shares at an extraordinary valuation. I will cover the CBA valuation below.

But first I will consider QE in a little more detail.

Will QE drive economic growth in the US?

To answer this question, we need not look too far into the past. QE has been a feature of monetary policy and economic management by major central banks since the GFC. It has been labelled as part of ‘Modern Monetary Theory’.

Over recent macro-economic history, we have seen from Japanese (since 2000), European and US QE programs (post GFC), that an excessive use of QE does not necessarily lead to either a lift or recovery in economic activity.

Indeed, zero or negative real yields can inhibit economic activity, whilst allowing highly indebted governments to manage a potential debt servicing crisis.

There is abundant evidence (Japanese and European ‘negative’ bond yields) that excessively low interest rates stall the flow of both risk and investment capital. Banks reduce their lending as interest margins decline and the confidence of companies to borrow is challenged by a low-rate environment. Business sentiment is not uplifted by excessively low interest rates because such rates normally suggest an outlook for weak economic activity.

QE and negative real yields in the US

The US government bureaucracy, the Trump Administration, the US Congress and the US Senate are staring at a government debt servicing crisis. The exponential growth in US government debt is well captured in the chart below.

Similarly, large US investment funds are facing an uncertain and potentially volatile USD outlook that may include:

- The premature replacement of the Fed Chair by a Trump appointee. This process may well be chaotic if Trump pushes aggressively and Powell refuses to resign. What will Congress do if this happens? How will the US bond market react?

- A Trump Fed appointee will likely move the Fed monetary policy guidance towards lower US bond yields - across the yield curve. The Fed, with Trump friendly appointees, will then be coerced to undertake QE.

- Cash rates would be aggressively cut followed by a QE program designed to lower the US government interest bill. To achieve this, both cash rates and bond yields would need to fall (as noted above) to between 2.5% and 3%.

- As rates fall, equity PER expansion is possible. However, with high PERs already in place (the S&P 500 index companies are trading at around 22x forecast earnings versus a 10 year average of 18x), an equity market rerating would still be dependent on ‘real’ earnings growth that will be confronted by rising tariffs, higher costs of doing business and fiscal policy adjustment – Bessent target of rebalancing the deficit from 6% to 3% of GDP; and

- Domestic focused US companies (importers) are disadvantaged compared to multinationals. The US equity index (measured by high weightings to 7 or 8 mega tech companies) will need those companies to continue to perform, whilst many others face pressure. The high PERs of some stocks may be supported by their international earnings that are magnified by a weakening USD: around 30-35% of the revenues of S&P 500 companies are obtained from outside the US.

Given the above, the reduction of exposure to the issues confronting US based assets seems a logical response. Indeed, after a sustained period of US exceptionalism, US asset managers will need to think carefully and hedge against the risk of USD depreciation. The USD has fallen 10% over the last 6 months against a basket of other currencies. However, initially they may ride a US bond market rally and stay exposed to potential PER expansion when (or if) QE rolls.

A Trump induced QE, with aggressive cash rate adjustment, will take markets into a period of heightened volatility, featuring more asset price inflation, that will be likely followed by a period lower investment returns, as the US debt bubble is navigated.

CBA – buy, sell or hold

Fisher Investments has made their buy call and it seems that they picked up $1 billion of CBA shares around $180 per share.

As I suggested above, two of the connected reasons for them buying CBA may be to gain an exposure to a rising AUD, via utilising a highly liquid and yielding equity.

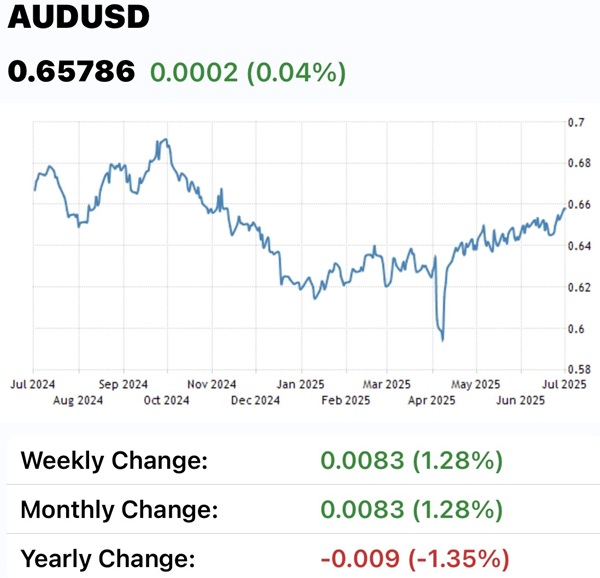

The call on the AUD is very much a call on the value of the USD. Is the USD likely to depreciate with a QE policy and interest rate manipulation?

The AUD has been weak against the USD since 2014 when it peaked at USD$1.10. Over FY25 it finished the year at 1.35% lower than where it started. However, since Trump’s inauguration in January, it has appreciated by 5%, punctured short term by the April tariff declarations.

I have long believed that the AUD has persistently traded below its fair value. A consistent trade surplus, a couple of fiscal surpluses, relatively low government debt and massive superannuation savings have failed to support the AUD – when basic economic theory suggested they should.

One explanation is the connection between our large superannuation savings and their growing flow towards offshore investments. Our super pool of $4.25 trillion is about 50% larger than both our economy and the capitalisation of the ASX. As funds have been increasingly allocated outside Australia, the AUD is sold to acquire foreign currency (mainly USD).

Our relatively small Commonwealth government bond market, 25% of superannuation assets, also acts to push our savings offshore and towards larger companies – both in and outside Australia.

That results in an increasing flow into ‘default index investing’. It may also explain why the Australian ASX 200 index has behaved similarly to the US indices – an excessive weighting of market performance explained by just a few stocks – and in the case of the ASX, by CBA.

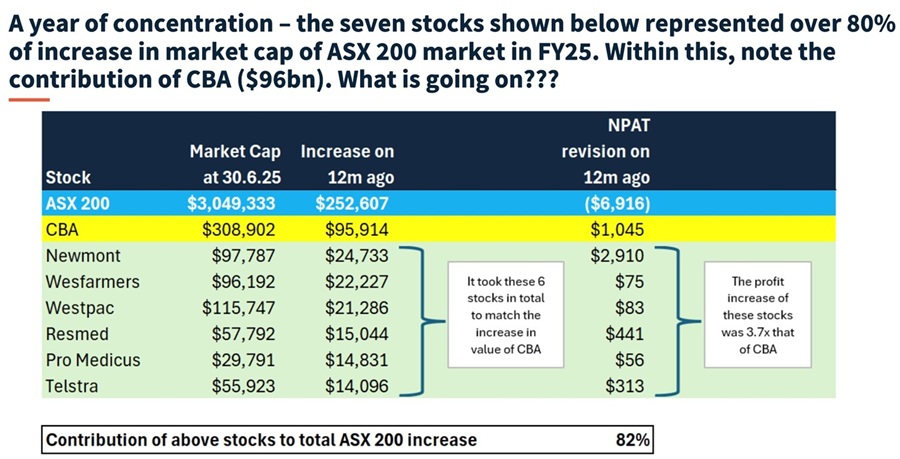

From the following table we note:

- CBA represents about 12% of the ASX 200

- The ASX 200 lifted by about 8% (price) in FY25 against earnings revisions of minus $6.9 billion from initial forecasts over 12 months ago

- Just 7 companies accounted for 82% of the index increase

- CBA alone accounted for 38% of the increase in the index

- CBA’s earnings revision of $1 billion for FY25 (from FY24 forecasts) resulted in a revaluation of 90 times that incremental profit performance.

To suggest that the CBA share price is confronting is obvious. Compare the forward price earnings ratio (fPE) of CBA at 29 or 30x with some of the largest US banks like JP Morgan Chase (fPE of 14x), Bank of America (fPE of 15x) or Wells Fargo (fPE of 15x). European banks are priced similarly, with HSBC on fPE of 15x, UBS on fPE of 17x and BNP Paribas at about fPE of 9x. Smaller European banks are far cheaper, and most of them trade at fPEs in the single digits. Of course, we acknowledge that forward price earnings ratios are just one simple metric for assessing a bank’s valuation.

We know that the share price on any day gives little indication of where its price will go in the next week, month or indeed year. Ultimately, market theory suggests that a company’s share will eventually trade at or around fair value. However, fair value is opinion based and is naturally biased by qualitative assessments and observations of market price behaviour.

This second point emphasises why CBA shares are highly sought by international investors. Its price has performed and that suggests it is more likely to continue to perform (i.e. momentum) as QE floods the US and world capital markets with liquidity.

In other words, the weight of money and default investing will support the CBA. But could a headwind appear to push against the relentless inflows towards CBA? Of course they could – financial history is full of such tales.

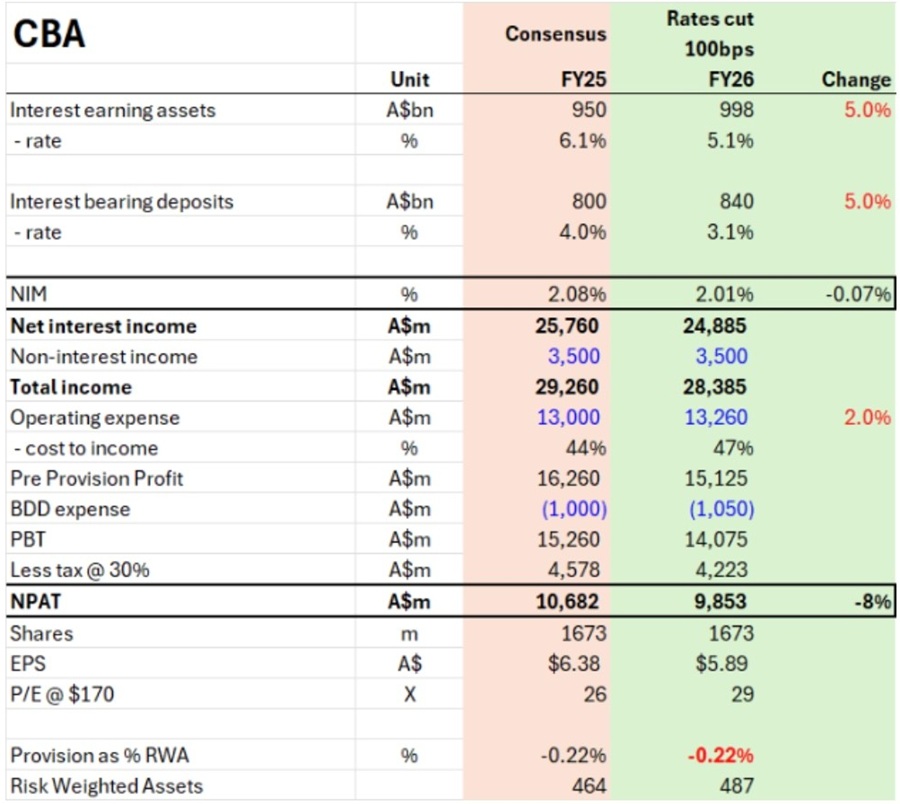

My final table, created by Clime analysts and drawn from bank analysts across the market paints a difficult outlook for banks generally and CBA specifically as (and if) the RBA cuts cash rates.

A projected reduction of cash rates by 1% over an operating year is tracked in the following table.

A reduction in cash rates, given a highly competitive mortgage market with regulatory and political oversight, will lead to a reduction net interest margins and profits.

CBA, more than its competitors, has done well to deal directly with its borrowers (with less reliance on brokers and intermediaries) and has a traditionally strong direct connection with retail deposit providers. That holds it in good stead, but it won’t stop an earnings decline, or a flat profit outlook that will challenge the 30x PER rating (at $180).

Also, alarming is that the market capitalisation is 12 times its ‘net interest revenue’. That multiple is more suitable for earnings, not for revenue.

Good luck to Fisher Investments. It will be interesting to see if they make money on their trade – and whether their hoped-for profit comes from currency movements or from the CBA’s share price – or both or neither.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.