More Australians are investing in offshore equity and bond markets, but they may underappreciate how currency fluctuations either cushion or exacerbate gains and losses in their portfolio.

For many investors, the decision to hedge the currency exposure on offshore investment portfolios is often seen as a binary choice akin to a coin toss – heads or tails, hedged or unhedged.

Investors spend much of their effort deciding which asset class to allocate to, but often devote less consideration to how decisions around currency exposure can dramatically improve the risk-adjusted returns of their portfolio.

The hedging decision and avoiding regret

When investors buy foreign assets, they obtain exposure not only to the underlying securities but also to foreign currency. Movements in exchange rates play a significant role in determining the performance of a foreign investment. A second-order decision is whether to hedge this foreign-currency exposure. Many investors implicitly weigh up their outlooks for the respective currency and their appetite for losses due to adverse currency movement (the so-called ‘regret tolerance’).

Regret theory assumes that investors are rational but base their decisions not only on expected payoffs (‘value’) but also on expected regret. Sebastien Michenaud and Bruno Solnik (2008) found that risk-averse investors dislike volatility, whereas regret-averse investors may prefer volatility to avoid regret for giving up on the large gains that may materialise.

They found that many investors, when considering both volatility and regret, tend to err towards regret avoidance, and under-hedge even when fully hedging is the optimal decision based on all available information and traditional risk-return optimisation.

It is little wonder then, according to their research, that approximately 39% of currency investors do not hedge, 34% adopt a 50% hedging strategy, 14% adopt of a 100% hedging strategy, and the remaining 13% adopt some other hedge ratio.

The impact of currency on global portfolios

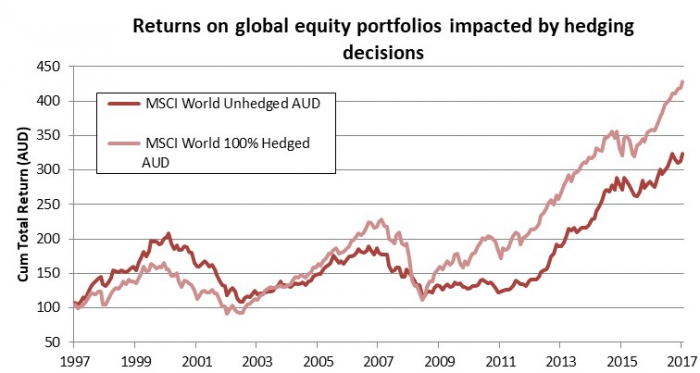

Whilst many investors make a binary choice to hedge 100% or not, our own research indicates that the optimal hedging decision varies considerably over time.

For Australian investors:

- If the AUD is appreciating, a hedged global equity portfolio outperforms an unhedged one.

- If the AUD is depreciating, an unhedged global equity portfolio outperforms a hedged one.

This can be seen from the graphs and table below.

| MSCI World Annual Return |

| To Sept 2017 | Unhedged | 100% Hedged |

| 1 Year | 15.9% | 19.6% |

| 3 Years | 12.3% | 10.7% |

| 5 Years | 18.1% | 15.0% |

| 10 Years | 6.1% | 6.7% |

| 20 Years | 5.7% | 7.3% |

Source: Bloomberg, MSCI

The outperformance can be substantial and persistent. In the table above, the unhedged global equity portfolio has outperformed the hedged by 3% annually for the last five years. That is, the AUD has strengthened and it was better to be hedged than exposed to the ‘weaker’ global currencies in an unhedged position.

So then, what is the ‘best’ hedging ratio that both captures good returns and prevents extremes of underperformance?

The optimal hedge ratio over the (very) long term

The AUD is often characterised as a commodity currency, meaning that its movements are correlated to commodity price cycles. This means that the AUD appreciates during economic booms when commodity prices are higher and depreciates when the cycle turns.

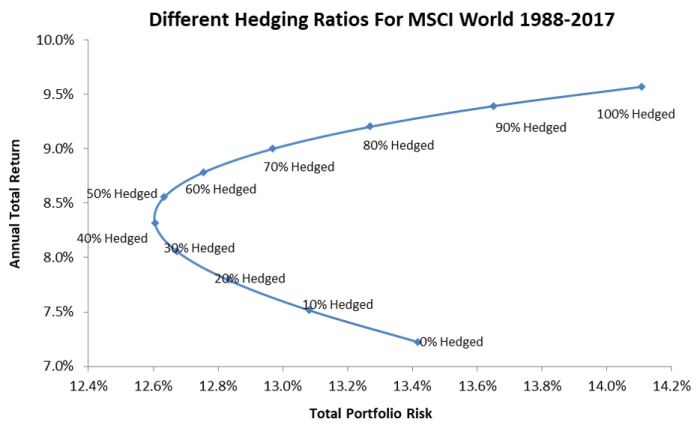

To figure out the optimal hedge ratio, a set of different portfolios were created using different hedging assumptions. Their returns vs. risk were then plotted over time, essentially creating an efficient frontier (series of possible return outcomes for a given level of risk) for different hedging solutions, as illustrated below.

| MSCI World |

| | Unhedged | 100% Hedged to AUD |

| Annual Return | 7.2% | 9.6% |

| Annual Risk | 13.4% | 14.1% |

| Return/Risk | 0.5 | 0.7 |

Source: Bloomberg, MSCI, Tempo AM

The graph above illustrates that, over this long run (about 30 years), the hedged equity portfolio generally outperforms the unhedged one. Unfortunately, while this analysis is interesting, it is not very useful for investors.

The difficulty in figuring out an optimal hedge ratio is that this ratio changes over time. Certain hedge ratios are ‘optimal’ for a certain time interval while others are ‘optimal’ for other time intervals.

For currencies, ‘optimal’ is a slippery concept

It is worth noting that while the 40% - 100% hedging ratio illustrated above is optimal over the very long term, during specific periods other hedging ratios may be better to avoid cash drawdowns required by hedging counterparties.

For example, during the GFC from 2006 to 2008, where the AUD/USD dropped from 0.98 down to 0.60, the best hedging strategy was to have no hedge at all (that is, exposure is left open to foreign currencies which increase in value as the AUD falls). Maintaining a 100% hedged strategy would have cost an extra -2.4% per year over these three years compared with not hedging.

However, extending the analysis an extra two years and including the period from 2009 to 2010 when the AUD/USD bounced back from 0.60 back to over 0.90 again, the optimal solution would have been to 100% hedge. It’s exactly the opposite of the previous analysis!

In this second scenario, maintaining a 100% hedge ratio over the full timeframe would have benefited Australian clients by nearly 6% annually over an unhedged portfolio.

Conclusions

The complexity of investing requires that portfolio management is best done by asset class or sector specialists, and currency should be no different.

Currency management requires specialist portfolio management skills, systems, analytical frameworks, and sell-side broker relationships that are different from mainstream asset classes. Specialist currency managers are also well placed to ensure trading execution is done in the most cost- and timing-efficient manner.

Furthermore, using currency hedging specialists, as opposed to embedding currency management within investment products allows for portfolio managers and products to be adjusted independently of the currency overlay avoiding unnecessary tax consequences and trading.

Joseph Bracken and Robert Chapman are principals of Tempo Asset Management. Tempo is a global equity alliance partner of Fidante, a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This article is in the nature of general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Reference: Michenaud, S & Solnik, B., 2008. Applying Regret Theory to Investment Choices: Currency Hedging Decisions, Journal of International Money and Finance, vol. 27, no. 5