The super system is once again in the media spotlight, this time for the Government’s proposal to wind back some of the tax breaks [estimated at $55 billion for 2024/25], via its ‘Better Targeted Superannuation Concessions’ tax (hereafter referred to as the ‘Div 296’ tax).

This measure will effectively impose a 15% tax on super earnings equal to the percentage of an individual member’s ‘Total Superannuation Balance’ exceeding $3 million for an income year. By applying the measure to TSBs, it captures both the accumulation and pension phases of super.

Somewhat controversially, the measure as proposed is not indexed for either inflation or wage growth, meaning that over time more individuals will be impacted than the 80,000-odd people (some 0.5% of all taxpayers) forecast during its first scheduled year of operation.

In addition, the method chosen to calculate the change to year-on-year earnings has many commentators and economists calling Div 296 a tax on unrealised capital gains, a position that, if true, would reverse decades of tax precedent and regulation.

I’ve spent near-on 30 years seeing the super system mature. In that time, I’ve advised individuals, including ultra-high net worth clients, on their wealth management strategies, of which Self-Managed Superannuation Funds (SMSFs) have become a key component since 2006-07.

I’ve also worked with APRA-regulated super funds and so understand the way in which superannuation earnings, and taxes thereupon, are calculated and equitably applied across vast memberships, sometimes numbering in the millions.

On balance, I think the Div 296 tax is a reasonable approach to improving the long-term sustainability not just of superannuation but the entire retirement income system. Here’s why.

Super – a tale of two sub-systems

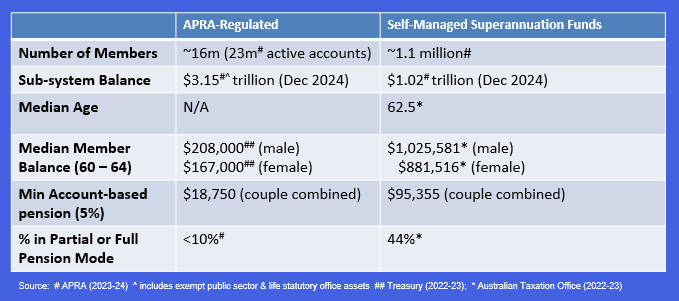

While the super system entered 2025 north of $4 trillion and with 17 million members in aggregate, it is better conceptualised as being two very distinct sub-systems, broadly consisting of APRA-regulated funds on the one hand and SMSFs on the other.

As the table below indicates, APRA-regulated funds account for about 94% of all members while holding approximately 76% of system assets.

SMSFs, by contrast, make up 6% of members but hold some 24% of assets.

SMSFs have significantly larger balances on average, with the median near-retiree couple holding a combined $1.9 million, five times the super held by the median APRA-regulated equivalent couple.

That, in turn, translates to a substantially higher level of minimum private income in retirement, were these respective balances to be fully converted into account-based pensions.

With recent reporting revealing that 42 SMSFs currently hold assets in excess of $100 million, it is unsurprising that interests connected to this sector are the most vocal in opposing the Div 296 tax.

Stabilising the retirement income system

Australia’s retirement income system is book-ended by the two key supports to retirement: the Age Pension and superannuation.

The latter was conceived as ‘a system of more adequate private provision of retirement income, sympathetically interfaced with the public pensions system’, according to its chief architect, Paul Keating. Tax concessions were seen as central to encouraging this private provision, beyond just the employee super guarantee contribution.

Given the tax arbitrage on offer between the top marginal rate and 15%, higher-income individuals have embraced super (often via SMSFs) as a perfectly legitimate way to optimise their financial affairs. After all, no one should feel compelled to pay one more dollar in tax than they are legally required to.

At present, the top 20% of income earners receive over 55% of the total benefits from earnings tax concessions, with 39% going to the top 10% alone.

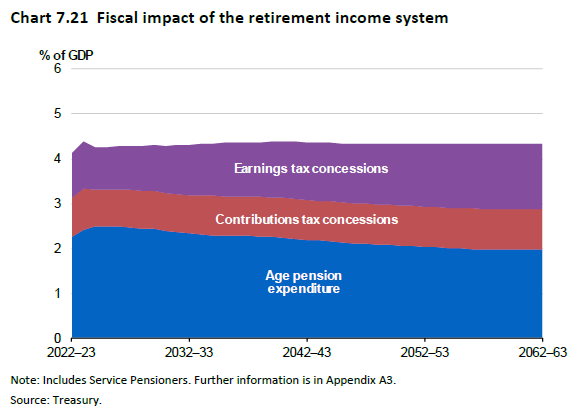

From a sustainability perspective however, these tax concessions now have a life of their own and will by the mid-2040s cost taxpayers more than the Age Pension, according to Treasury’s latest Intergenerational Report, and the chart from it below.

It is estimated that between now and 2062-63, the cost of the Age Pension will reduce from 2.3% to 2% of GDP. Super tax concessions will by then be 2.4%, driven primarily by earnings tax concessions rising from 1% to 1.5% of GDP.

That would be ironic indeed, with the system implemented to contain the burgeoning expenditure of the Age Pension costing taxpayers more than the policy problem it set out to fix.

Earnings tax concessions grow in line with overall system growth, and so the only way to throttle back this tax leakage is to target high balance members, as the Div 296 proposal seeks to do.

In effect the Government is saying that $3 million for an individual (or up to $6 million for a couple) is a reasonable amount to accrue in superannuation, and anything beyond should not be as generously taxed.

Given that $4 million of such a couple’s combined super could currently sit in non-taxed pension accounts once 60, with the balance taxed at less than 15% (more likely around 7% depending on investment composition, franking credits and the accumulation/pension split) it is difficult to argue otherwise, when the median retiring couple today has about one-tenth that amount.

Back to the future – sort of

Having been in super for as long as I have, I can’t help but make the connection to the former Reasonable Benefit Limit (RBL) regime, which commenced in 1990 and provided two indexed amounts each year; a lump sum RBL commencing at $400,000 and a pension RBL commencing at $800,000, beyond which super benefits were taxed at the highest prevailing marginal tax rate.

The RBL regime ended with the 2006/07 Budget and the then-Government’s ‘Simpler Super’ reforms, which also removed a host of other taxes on different elements of super benefits.

In that last year of operation, the lump sum RBL was $678,149 and the pension RBL was $1,356,291.

I’ve indexed the above RBLs for average weekly earnings from 2007-08 up to June 2024, and the equivalent pension RBL (if still in existence) would be just over $2.5 million.

Which is suggestive that the proposed Div 296 tax limit of $3 million in 2025 is sensible, while the Greens stance of wanting it lowered to $2 million isn’t. Further, taxing amounts above $3 million at 15% is markedly more equitable than at the top marginal rate, as happened with RBLs.

While it is farcical to suggest that the median Australian worker will accrue a super balance in excess of $3 million inside 40 years (Treasury modelling suggests a balance in 2019 dollars closer to $500,000 by 2060 for males, 10% lower for females), given that RBLs were indexed to wage growth I believe a precedent exists to similarly index the Div 296 tax, and that indexation should be implemented sooner rather than later.

As for the taxing of unrealised gains, I would note that members of APRA-regulated funds already are, insofar as the daily unit price for any accumulation option contains an estimate of fees, costs and taxes, including an estimate of realised and unrealised gains periodically adjusted to ensure estimate matches actual by year’s end. That is merely a function of the unit trust structure of such funds, and necessary to maintain equity between members entering and exiting either an accumulation option or the fund itself.

Right-sizing super concessions

Div 296 is trying to repair some of the earnings tax largess that was created in that 2006/07 Budget, which saw an unprecedented amount of wealth flow into the super system prior to 1 July 2007.

I know this because I was an SMSF adviser at the time, and it is to this day the most hectic financial year I’ve ever experienced, helping wealthy clients channel up to $2 million of after-tax contributions combined, often from other wealth vehicles. That was thanks to the ‘$1 million transitional non-concessional cap’ which operated between 10 May 2006 and 30 June 2007, and the promise of a retirement free of both income tax and capital gains tax once in SMSF pension phase past the age of 60.

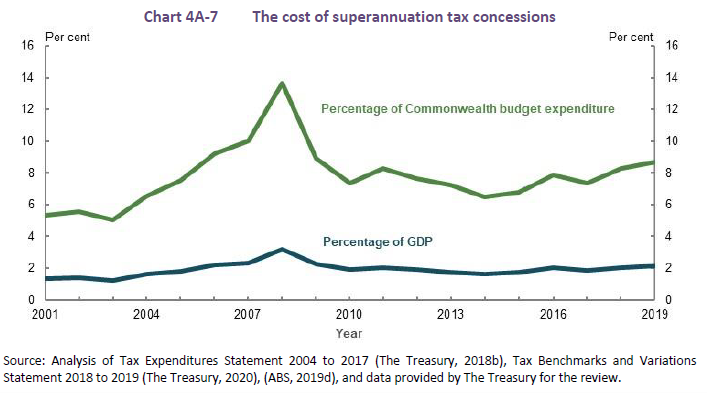

It is no coincidence that the cost of tax concessions in 2007-08 was exorbitantly high at $46.6 billion, as the below chart from the Retirement Income Review depicts.

Those with the means were merely taking advantage of the opportunity on offer, as was their right, often with the help of professional advice.

The consequence, however, is that those with a super balance larger than $3 million increased from less than 5,000 people in 2005 to over 30,000 in 2017, now some 80,000.

A superliner in need of a rebalance

In a piece penned in 2020, I spoke of the super system as a ‘directionless supertanker’; gargantuan in size but without any real sense of purpose.

With the legislating of an objective for the super system late last year, being “to preserve savings to deliver income for a dignified retirement, alongside government support, in an equitable and sustainable way”, it now is more akin to a mega cruise ship carrying thousands of passengers and crew.

These modern floating cities are cavernous, complex entities allowing people with different aspirations and resources to sail together; albeit enjoying different experiences according to individual preference and financial capacity.

From inboard cabins for the budget-conscious to presidential suites for the luxe inclined, it is the responsibility of the cruise company, and the captain in charge, to balance the interests of all aboard so that everyone arrives at their destination better for having taken the journey, despite the occasional bumpy episode.

That’s the challenge that this Div 296 proposal seeks to address to the benefit, in my opinion, of the entire retirement income system in the longer-term.

Harry Chemay has over 28 years of experience in wealth management and institutional asset consulting. Initially a private client adviser with an SMSF focus, he now consults across wealth management, FinTech and APRA-regulated super funds, with a focus on improving post-retirement outcomes.