In the first ten weeks of 2016, share markets were often described as turbulent. Globally, shares shed 11% of their value between the start of the year and mid-February. Predictions of a global recession were frequent and shrill. Oil and iron prices tanked. Adding further to the gloom, a cleverly-marketed research report did its rounds, predicting a collapse in Australian house prices and bank shares.

Then, the widespread gloom dissipated. By mid-March, key share indexes in the US and Australia – and, surprisingly, those in emerging economies – had recovered most of their earlier losses. Bulk commodity prices shot upwards, with iron ore up by an impressive 66% from its low point. Bank shares were keenly sought.

Before drawing out the five lessons, what were some of the causes of these gyrations?

Markets often swing widely when big investors take or unwind similar positioning

In January and early February 2016, many large investors – hedge funds particularly - adopted similar investment decisions. This included selling, and in some cases shorting, assets that would likely plunge in price when China fell into a hard landing.

Fiduciary’s Michael Mullaney described the January sell-off in shares as reflecting “an oversold condition with everyone on one side of the boat”. Later, the rush to close out these short positions added intensity to the share market rebound, often at significant cost to investors still holding the short positions that were so popular among hedge funds previously.

Investors put too much emphasis on soft numbers on the Chinese and US economies

In January and early February, many investors interpreted data on China’s external trade and manufacturing as confirming the ‘contraction’ of the Chinese economy. Subsequent information shows that continuation of useful gains in retail sales and the services sectors in China have partially offset the slowing growth in manufacturing and heavy industry. China faces many problems, but the hard landing predicted since 2011 has, so far at least, been avoided.

In the US, market sentiment in the early weeks of the year focussed too much on the risks of consumer spending remaining soft and on US banks being crippled by the write-downs on their energy loans. As it turned out, US job creation and consumer spending have continued to track at reasonable rates.

Lower oil prices hurt some … but benefit many

Recently, the key indexes of average share prices have often moved in lockstep with the oil price. It seemed as though the oil price was being taken as an indicator of global growth. As well, there were (exaggerated) concerns the lower oil price would create a banking crisis.

In reality, the fall in the price of oil – which results more from excess supply than from contracting demand – is bad news for most energy producers but will, over time, favourably affect many businesses (lower costs) and households (enhanced spending power).

Investors need to be wary of predictions of an imminent housing crash in Australia

Periodically, claims are made that Australian housing is in a bubble, house prices are about to crash and the prices of our bank shares will crumble because of bad debts.

A report marketed in January and early February by a local portfolio manager and a UK hedge fund argued our house prices and bank shares could soon lose half or more of their value. Their shrill conclusions were given front-page coverage in The Australian Financial Review. It carried no alternative expert views and gave little recognition to the low default rates that are a feature of housing finance in this country given that most loans are full-recourse to the borrower. Excesses in the Australian housing market are usually worked off by average house prices moving sideways for a few years; falling prices are rare.

The Australian Financial Review’s Christopher Joye suggested investors who’d shorted bank shares would be scrambling to buy them back to close out their positions. Subsequently he commented,

“Bank stocks have bashed the ‘johnny-come-lately’ hedge fund barbarians that stormed the gates last week. The catalyst has been fact triumphing over the hedge funds’ book-spruiking fiction.”

What lessons have we learned?

I have distilled these five lessons from the last three months of turbulence:

- When sentiment on the global economy is fragile, the accumulation of even mildly negative news can drive share markets a lot lower. (Extreme things also happen when the prevailing view in share markets is ebullient. For example, a year ago, share markets rose on both good and disappointing news on economic activity: strong data because they suggested better profits; and weak data because they meant interest rates would be lower for longer).

- When expectations in share markets build up in a largely uniform way, investor positioning – and the subsequent unwinding of those positions – can trigger big moves in share prices.

- Sometimes (such as 2008), a sharp fall in share prices portends a lengthy period of difficult times for investors in shares. At other times (for example, 2011 and, it seems, early 2016), the crash in share prices soon corrects and may well be quickly forgotten. As Paul Samuelson famously quipped in 1966, the US share market had predicted nine of the previous five recessions.

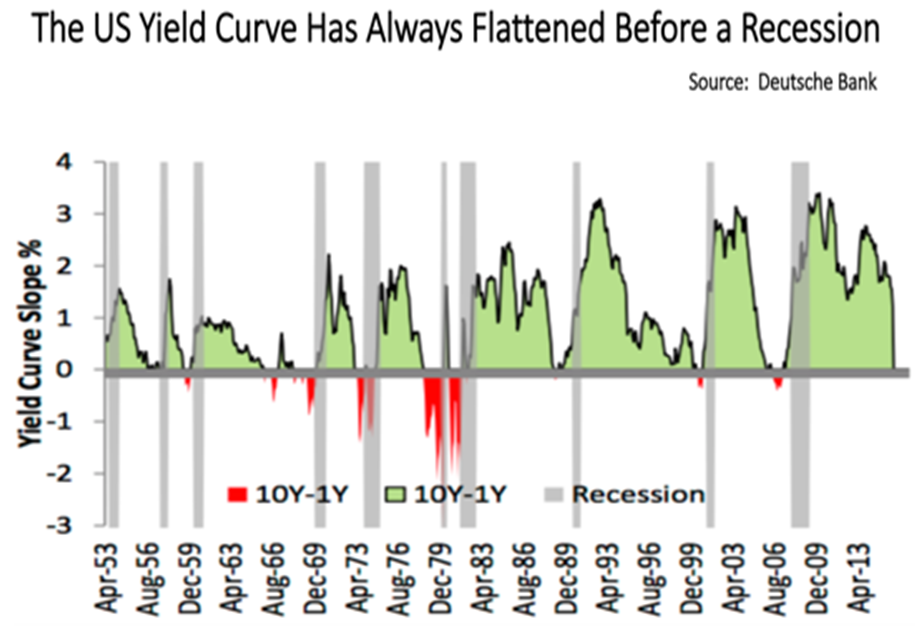

- The challenge for investors is to pick whether or not a share market sell-off will be followed by a lengthy slump in share prices. This requires giving fresh thought to the risk of an early recession. The traditional indicators of imminent recession include, but are not limited to: a sharp rise in unemployment; a sudden tightening in credit; and a flattening or inversion of the yield curve.

In the US, the shape of the yield curve has a good record in predicting recessions, as the chart below shows. But much depends on investor confidence and sentiment, and that’s hard to foretell.

- Investors were too pessimistic early in the year on global growth prospects. Now, there’s a more balanced outlook, with shades of grey in assessments on economic prospects in China and the US. But the key concerns of many investors – such as the sustainability of negative nominal interest rates in Europe and Japan and the stretched valuations on shares in companies with strong growth in earnings – have not been overcome. Further swings in investor sentiment should be expected in the months ahead.

Perhaps the most important lesson is that at times of stress, sensible diversification, including a good allocation to cash, makes sense.

Don Stammer chairs QV Equities, is a director of IPE, and is an adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund and Altius Asset Management. The views expressed are his alone and do not address the needs of any individual. This paper draws on material in a column by the author published in The Australian.