While equity market forecasters are wrong about half the time, they tend to have a higher success rate than economists, who predicted a US recession in 2024 and inflation falling back to 2%. More recently, the latest US labor report showed that the number of new jobs created in December blew past consensus forecasts by more than 3 standard deviations.

Why is economic modeling so hard?

Economic forecasting warrants a stronger adjective than hard. Its exceptionally challenging and complex. While several factors are at play, at its core, gross domestic product isn’t a static measure like wealth, enterprise value or stock market capitalization. Instead, GDP captures the dynamic flow of capital within an economy, meticulously tracking expenditures — their magnitude, location and source — and comprises many variables moving in conflicting directions.

As a result, the aggregated data streams used in economic modeling can sometimes make a change in trend or direction hard to see. Seemingly small or immaterial data points are often underemphasized if not overlooked. Often the most critical datapoints, such those that mark the end or beginning of meaningful directional changes in the flow of capital, reveal themselves years later as important inflection points.

This is where a bottom-up approach may complement a top-down forecast.

Getting at the economic cycle through the capital cycle

The purpose of capital markets is to bring together society’s savers, those seeking returns above cash yields and those with ideas but in need of funds. In exchange for capital, entrepreneurs are willing to give up some of the potential spoils. Since capital is allocated in accordance with the potential utility and risk of the project, where capital is being allocated to and from signals where the private market sees growth and contraction.

For example, we can observe this in the very long but weak business cycle following the 2008 financial crisis. Households and banks undertook balance sheet repair that warranted years of austerity and deleveraging that deflated economic growth. With anemic revenue growth, developed market companies only added to the malaise by offshoring, which lowered spending and expenses. With deflation risks mounting, central banks rekindled a capital cycle by artificially suppressing borrowing costs. While a new capital cycle was borne, it wasn’t the one many had hoped for, fueled by tangible fixed investment. Instead, newly created capital was cycled to shareholders via dividends and stock buybacks, culminating in one of the longest economic cycles in decades, one that produced immense wealth for many equity owners.

So where is capital flowing today and does the answer to that question explain the current state of US economic exceptionalism? More important, can it give us insight into the future?

The capital cycle now and why it matters

A lot of goods consumed in the US, including many related to national security, are manufactured outside the country. As a result, companies haven’t had to create tangible capital because China has done it for them to the benefit of shareholders.

However, in recent years, the combination of COVID, rising geopolitical tensions and prospects for future tariffs has brought about a shift. An efficient, low-cost system is being exchanged for one where products are produced more simply and closer to home. Following many years of US corporate capital expenditures falling relative to sales, today it’s reversing. A new capital cycle has emerged, but this is only part of the narrative.

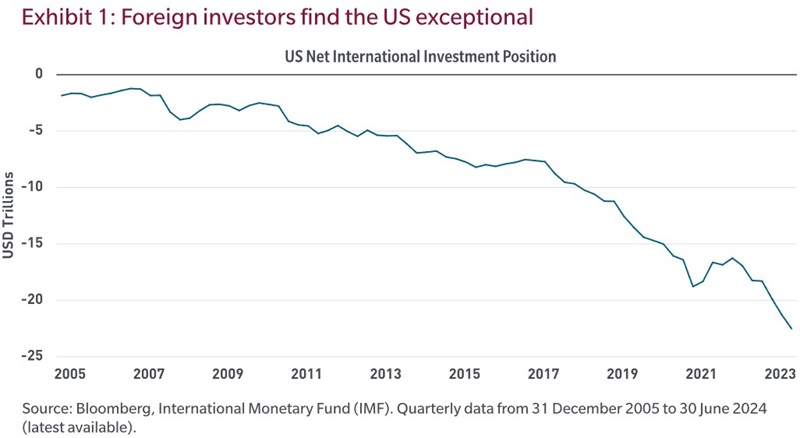

Since the US is the primary home of artificial intelligence, it’s sucking up the world’s investment capacity. The exhibit below illustrates the net level of US international investment (the difference between US residents’ investments abroad and foreign investment in the US). At -$22 trillion, it’s more than quadrupled since the runup to the global financial crisis.

The investment needs associated with the AI ecosystem are massive. While there are over 8,000 data centers globally, the bulk are in the US. Think of these as AI factories that turn energy and data into human-like outcomes. The physical and capital needs for data centers alone, never mind that the demand for cooling, power and the like are enormous.

This shifting use of capital helps explain US exceptionalism and perhaps supports the notion that the recent US labor report shouldn’t have been as surprising as it was.

The capital cycle of the 2010s deflated cost and produced very little economic growth but fueled huge profits and wealth for stock owners. That capital cycle has ended. Today’s cycle is different. It’s inflating costs (equipment and labor), driving growth, US exceptionalism and higher interest rates. What remains to be seen is how this will affect profits and thus stock prices.

Future profits and equity returns

US profits are high as companies have been able to maintain the elevated prices from the COVID-stimulus period. Additionally, investors are enthused by the prospect of future corporate tax cuts and continued superior US GDP growth and extrapolate those into continued earnings gains.

While that’s a possibility, the changing capital cycle points to a potentially different outcome. Recent investments have already produced new products across varying industries. Increasing supply, particularly that comprising goods better or cheaper than existing ones, challenges the pricing power of incumbents and forces them to invest more. Lower prices and higher costs are a high hurdle for companies to clear, which is what the prices of most stocks imply today.

Take consumer goods. Traditionally, brand power has been a substitute for consumer due diligence, and it has delivered market share and profits. AI has changed that. An online query via a common search engine leads you to products with large advertising budgets, but large language models (LLMs) will go further, cutting through marketing noise and delivering goods tailored to consumers. LLMs will become a workhorse for the consumer by reading what industry experts have to say, checking out every customer review, etc. In other words, AI will give consumers agency, posing immense challenges and bringing changes across multiple industries, potentially disappointing the very high expectations of investors today.

Conclusion

There has been a substantial change in the capital cycle. Instead of funding dividends and buybacks, many companies are funding tangible projects. While that could mean more growth and inflation, it would also mean a whole different set of winners and losers.

Looking ahead, stock market leaders will likely be those companies insulated from competition with the ability to protect profit margins. Laggards will likely be those susceptible to ankle-biters forcing change. Like generals fighting the last war, benchmarks are positioned for a paradigm of the past, not the future. We think that forward-looking active managers who employ a capital cycle lens will outpace the pack.

Robert M. Almeida is a Global Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager at MFS Investment Management. This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to invest in any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It has been prepared without taking into account any personal objectives, financial situation or needs of any specific person. Comments, opinions and analysis are rendered as of the date given and may change without notice due to market conditions and other factors. This article is issued in Australia by MFS International Australia Pty Ltd (ABN 68 607 579 537, AFSL 485343), a sponsor of Firstlinks.

For more articles and papers from MFS, please click here.

Unless otherwise indicated, logos and product and service names are trademarks of MFS® and its affiliates and may be registered in certain countries.