Some stories bear repeating. Back in 2013, Chris Cuffe wrote an article in Firstlinks (then Cuffelinks) entitled Until debt do us part, Act 1.

Its basic premise was that concerns and commentary about government, national and household debt were often off the mark. It pointed out, from an accountant’s perspective, that 'debt to GDP' ratios were a mix of stock and flow numbers. The level of debt is a stock item while GDP or national income is a flow item.

Can we service our rapidly-rising debt?

This mix of accounting concepts distracts us from the primary issue that debt creates, namely capacity to service. The article suggests that debt servicing ratios are more helpful in determining our level of concern and should be the focus of commentary.

With Australia’s household debt at record levels (see chart below), our general government debt about to reach levels not seen since WWII (due to the Covid-19 response) and foreign debt now in excess of $1 trillion, it’s time to remember Chris Cuffe’s basic accounting principle. Undoubtedly, we will soon start reading horror stories about debt. Be prepared.

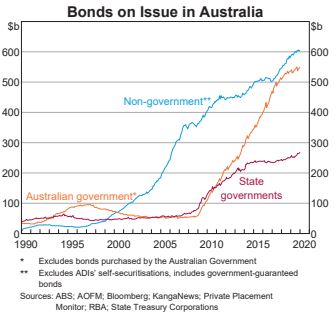

As shown below, government bonds on issue have already risen rapidly since 2010, and will exceed $1 trillion within six months after funding the stimuls packages.

The current economic policy response to Covid-19 continues to unfold. Its economic aim is to cushion the economy from the impact of its policies to control the health crisis (lockdowns).

The scale of the economic response is lifting debt to the point where previously agreed up debt ceilings are being lifted. While in the United States, this has caused political grandstanding and generated market uncertainty, in Australia it has passed by with little comment.

Economy is still functioning

On whatever measures you chose to use (and, debt to GDP, sadly, is the most common) Australia’s government debt is low by world standards. It is set to rise, but even if it were to double, it would still sit below the debt to GDP ratios of nations with comparable standards of living.

What about our ability to service this new debt? This depends primarily on two things, our income and the interest costs.

Without doubt our income will take a hit this year. It may well be subdued for a few years to come. No one really knows the endgame of Covid-19 but a vaccine does seem probable, but with considerable delay. That said, the economy has not stopped in its tracks. Income will be down but not out.

An unemployment rate of 10 or 15% is an economic and social disaster but it also says that 85-90% of the economy is still operational. There will be wages earned, profits made, and taxes paid. There will still be a flow of income to the government from which debt payments can be made.

And what about the cost? Today interest rates are at historical lows. Low borrowing costs can be locked in for a decade. Rates will rise but not soon. In the meantime, we have the capacity to rebuild our economy, reduce unemployment, rethink our ways of doing business and adjust our priorities.

I don’t wish to underplay the risks associated with taking on debt. It’s never a riskless exercise, but likewise, I want us to understand the metrics that matter.

What are the metrics that matter?

GDP or national income in 2019 was almost $2,000 billion. Government debt outstanding was almost $600 billion in the latest Reserve Bank chart shown above (released on 4 March 2020). According to the budget papers, government debt in 2018-19 was estimated at $373 billion with interest costs of $14.1 billion while government revenue was $485 billion.

At the time of writing the government had announced some $350 billion in new spending. The largest items are the JobKeeper, business support and JobSeeker programmes. The exact timing and magnitude is not known and further programmes may be required.

Taking the estimate of $350 billion as a base number for new debt due to spending programs, this adds $0.9 billion per year in interest costs. However, if government revenue falls by say 20% or $100 billion new debt could rise to $450 billion and total new interest costs of $1.1 billion.

The government is already paying $14.1 billion per year in interest costs. Total annual interest costs would rise to around $15.2 billion under this new scenario. Is this manageable? Yes. A resulting debt service ratio of 3.9% is well above that of recent years but is on par with levels seen during the 1980s and 1990s.

In a nutshell, the increase in debt resulting from new government spending programmes and a decline in government revenue is manageable. While we would prefer not to be in this position, from a debt financing position it is not a crisis.

We have been here before and we will come out the other side.

Hans Kunnen is the Principal at Compass Economics and was formerly an economist with Colonial First State and St George Bank.