With iron ore slumping to five-year lows and Peter Reith suggesting Australia is headed for an ‘inevitable’ recession, the subject of growth should be a major focus for investors. Our previous article on understanding growth showed some tools available to companies to manipulate revenue growth. In this article, we look at understanding earnings per share growth and its funding.

If the point of investing is to forego expenditure today with the objective of improving purchasing power in the future, then this goal is enhanced by the pursuit of both value and growth. Value cannot be estimated in the absence of an estimate for growth. ‘Growth’ and ‘value’ must be two sides of the same coin.

Capital required to generate growth

Analysts and investors tend to focus purely on the growth that flows out of a company as measured by earnings and dividends. You will also find references to earnings per share growth in corporate communications about executive remuneration and mergers and acquisitions. Companies will explain that a proposed acquisition is earnings per share ‘accretive’ without much discussion about the impact of funding choices on investor’s long-term returns.

Focusing only on earnings growth can lead investors astray. Take the example of ABC Learning Centres. For years, the company attracted a legion of fans as earnings swelled from $12 million in 2003 to $143 million in 2007. Focusing only on the earnings growth however ignored the funding that was employed to drive it and ultimately entrapped those investors enamoured only with headline earnings growth numbers.

In my experience, business owners tend to focus on the capital required to generate a dollar of earnings much more than equity analysts covering stocks. Indeed, how many dollars are required to fund the growth in earnings is arguably more important than the dollars of earnings themselves.

Suppose $1 million is invested in a manufacturing business that produces a cash profit after tax of $400,000, representing a 40% return. Visions of grandeur cause the owner to expand the operations geographically and after investing another $1 million the following year in a second factory, profits grow 25% to $500,000.

A 25% growth in after-tax earnings is nothing to sneeze at. Indeed, such growth rates are pursued vigorously by professional investors.

However, thinking beyond the earnings growth reveals what a poor investment the second factory is. While earnings have grown, more equity has been contributed to the business to achieve that growth. Invest more funds in a bank account and interest earnings will rise and the only property, plant and equipment (PP&E) required is a rocking chair.

The second factory required an additional investment of $1 million and despite this 100% increase in equity, earnings grew only 25%. Putting aside issues relating to ramp up, the second factory has returned just 10% and that presumes all the growth came from the new factory, not from the older facility.

Not all growth is good

There is good growth and there is bad growth. Focusing only on the earnings cannot differentiate between the two. Growth is only good when each dollar used to finance the growth creates more than a dollar of long-term market value.

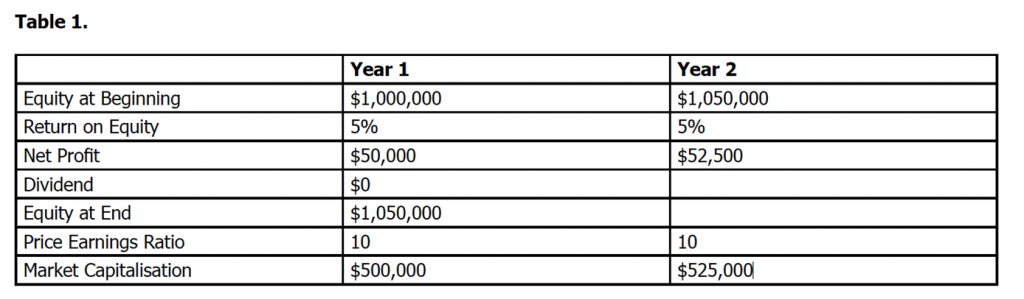

Table 1 shows a company whose shares are trading on a price earnings ratio of ten times. In Year 1 when the company earned a profit of $50,000, the stock market was willing to pay ten times that profit, or $500,000, to buy the entire company. The company begins Year 1 with $1 million of equity on its balance sheet, and in the first year, it generates a 5% return on that equity (or $50,000). Management decides that they need that money to 'grow' the business and so decide not to pay any dividends. That decision will cost shareholders dearly.

By keeping the profits, the equity on the balance sheet grows from $1 million at the start of the year to $1.05 million at the end. In the second year, the company again earns 5% on the new, larger equity balance, giving a profit of $52,500.

So on the surface things look rosy. The company is growing. The equity has grown, the profits have grown and management is drafting an annual report that reflects their satisfaction. But management has, perhaps unwittingly, dudded shareholders.

Shareholder returns are made up of dividends and capital gains. If a dollar is earned but not received as a dividend, it should be a capital gain. If not, it has been lost and management may be to blame. Every dollar that a company retains by not paying a dividend should be turned into at least a dollar of long term market value through capital gains.

The company in Table 1 has not achieved this, and although the company appears to have grown, shareholders have lost money. How? The company ‘retained’ all of the $50,000 of the profits it earned in Year 1. The shareholders received a gain of only $25,000. The company failed to turn each dollar of retained profits into a dollar of market value. If this were to continue, investors should insist that the company stop growing and return all profits as dividends and if that is not possible, the company should be wound up or sold.

The characteristic to search for, and avoid, is declining returns on incremental equity. This is precisely what happened to ABC Learning Centres and even an investor without a forensic accounting background could have spotted it.

Today, we see this at a range of businesses. Over the last decade, Virgin and Qantas have both seen declining returns on incremental equity. Equity contributed by shareholder owners of AMP has increased from $5 billion in 2010 to $9.7 billion in 2013 and yet profits have declined from a reported $775 million to $672 million. Over at Brambles, equity contributed by owners has risen from $1.4 billion in 2005 to $6.4 billion in 2014, but reported profits have grown only from $528 million to $619 million. At Newcrest, ten years ago the company earned $130 million on $802 million of equity. By 2014, shareholders have contributed $13 billion and despite this altruism the company has managed to earn just $315 million.

Ben Graham’s observation that the market is a weighing machine in the long-run is timeless. The share prices of all of the above examples have produced uninspiring and even some negative returns over a period of ten years.

Not all growth is good but you will do just fine as an investor by focusing on those businesses whose earnings march upward over the years at a faster rate than the rate of increase in the capital used to finance that growth.

Roger Montgomery is the Chief Investment Officer at The Montgomery Fund.