It is a stately process, and one that approaches the level of a ritual. In Australia, large companies announce their intentions to buy back shares using some of their excess cash. They mail out explanatory notices to their shareholders and invite them to participate in the buyback.

Everyone gets something: the company buys back shares, typically at a discount to their market price; remaining shareholders get higher earnings per share, and exiting shareholders, through the alchemy of tax, can sometimes get a financial benefit too. It is an almost perfect example of cooperative capitalism.

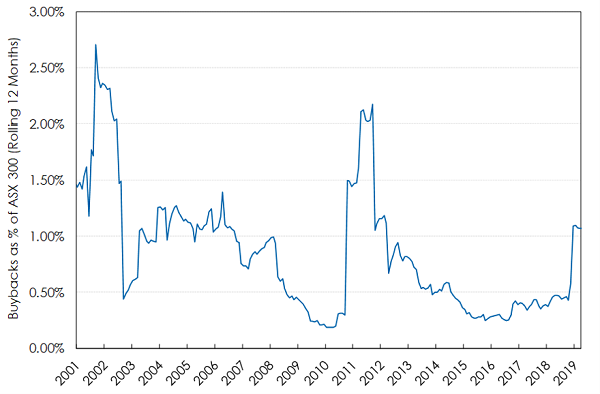

The only drawback is that it occurs in a small market at the bottom of the world. This is a description of the buyback regime in Australia, where for years companies have balanced the interests of investors seeking dividend income with those seeking earnings growth. Corporate share buybacks overall have consistently been 1-2% annually of overall market capitalisation in Australia over the past 20 years.

In the US, a different process unfolds

In the US, with low taxes on dividends but no dividend imputation, off-market buybacks are relatively unknown. But on-market buybacks have surged in the past 20 years, up to 3% annually of US market capitalisation. An even greater share of profits on average have been used to buy back shares than to pay shareholder dividends. Instead of everyone getting something, some get a lot. Current shareholders receive a boost to earnings growth from a lower share count. Company executives (whose compensation is frequently based on earnings growth accompanied by share price targets) often see the value of their compensation rise significantly.

Dividend-focused investors get little, and those looking for increased corporate investment – investment that offers the prospect of boosting employment – can also be disappointed. Instead of the cooperative capitalism that characterises off-market buybacks, this is a capitalism that favours management and shareholders, each of whose focus has appeared increasingly short-term in recent years.

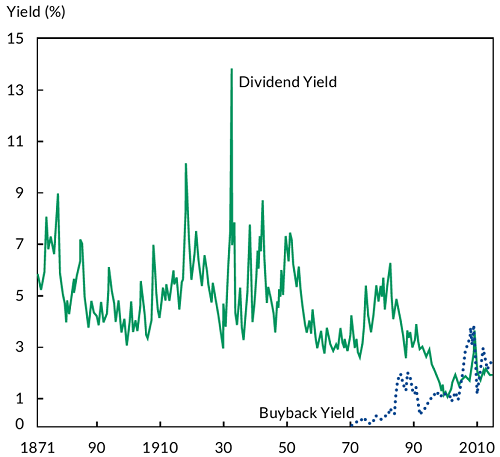

Traditional corporate finance theory split corporate profits into earnings to be retained, and those to be distributed to shareholders as dividends. During the 1980s, however, this model was revised – at least in the US – by deregulation, the hostile takeover movement and a new ideology of maximising shareholder value. By the end of the millennium, US corporate executives became focused on using repurchases, as well as dividends, as an important way of distributing corporate profits to shareholders. Chart 1 shows the increase of buybacks relative to dividends by US companies over time. Buybacks by US companies now constitute the single largest use of corporate profits.

US corporation dividend yield and buyback yield

share buybacks

Source: Straehl and Ibbotson, ‘The Long-Run Drivers of Stock Returns: Total Payouts and the Real Economy’, Financial Analysts Journal 2017.

In theory, corporate stock buybacks are a healthy financial activity

The underlying rationale for buybacks is that a company without significant profitable investments to be made is better returning profits to shareholders, either through buybacks or dividends. The two modes of distribution, however, are fundamentally different. Payouts through dividends increase the income return of shareholders. Buybacks increase the price return per share, since a holding investor’s share of the company through the buyback is increased on a per share basis.

They do so in two ways: in the short term, by providing a price return through the increased demand created by the buyback, and in the medium term by providing increased earnings per share, since the number of shares is reduced going forward.

The two effects together can be combined into a single expression of buyback yield which is the change in a company’s aggregate shares outstanding. US companies bought back an estimated 2.8% of their shares in 2018; ASX companies bought back about 1%.

Buybacks as a % of market capitalisation for the ASX 300 (rolling 12 months)

Source: Vinva Investment Management

Stock buybacks have unequivocally improved corporate earnings growth – mathematically, they must – but another collateral benefit has been company management compensation. Since large-scale, open-market repurchases give a boost to a company’s stock price, some of the prime beneficiaries of stock-price increases are the same corporate executives who decide the timing and size of the buybacks.

In addition, until the regulation was changed in 2017, performance-based executive compensation – much of it tied to buybacks – also received favourable corporate tax treatment.

The aggregate effects of stock buybacks

The most relevant question with respect to buybacks, however, is not whether they are productive or not. Instead, it is whether a practice that appears to have contributed to large growth in market capitalisation is a stable one at an aggregate level. In particular, the use of debt to fund stock buybacks probably deserves greater scrutiny.

A significant percentage of US stock buybacks over the past ten years have been funded by debt. In 2017, for example, roughly one-third of all US stock buybacks were debt-funded. Global large-cap companies with intangible assets in their brand and franchises, including franchise brand companies such as McDonald’s, YUM! Brands, and Domino’s Pizza Inc., have bought back so much stock and issued so much debt to do so, that they have negative balance sheet equity – that is, the book value of their assets is less than their liabilities.

With central banks still providing ample credit and liquidity to financial markets, buybacks look set to continue over the short-term. US corporate share buybacks are so far setting a record pace this year, even higher than their record 2018 levels. For both corporate management and shareholders, earnings growth is cheap – to generate it, all management needs to do is keep buying back shares. It’s hard to see an end to this trend, unless government regulation or tax treatment changes.

Impact of stopping buybacks on US market values

The US stock market, which makes up 63% of the MSCI World Index, continues to be at a 33% premium to the rest of the world (in aggregate, on a trailing price/earnings multiple basis). However, if the stock buyback component of 9% average annual earnings growth over the past five years for US companies were to disappear over the next five years, the cumulative loss of earnings would push the S&P500 price/earnings multiple to 23.5x. This compares to the rest of the world’s trailing price/earnings multiple of 15x. The discrepancy in valuations between markets alone should give an investor allocating between regions cause for concern.

If stock buybacks in the US stop for any reason, both management and investors alike will have to shift earnings per share expectations downwards. Based on comparable recent history, that wouldn’t be pretty.

John O’Brien is a Principal Adviser at Whitehelm Capital, an affiliate of Fidante Partners. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.