The Weekend Edition includes a market update plus Morningstar adds links to two additional articles.

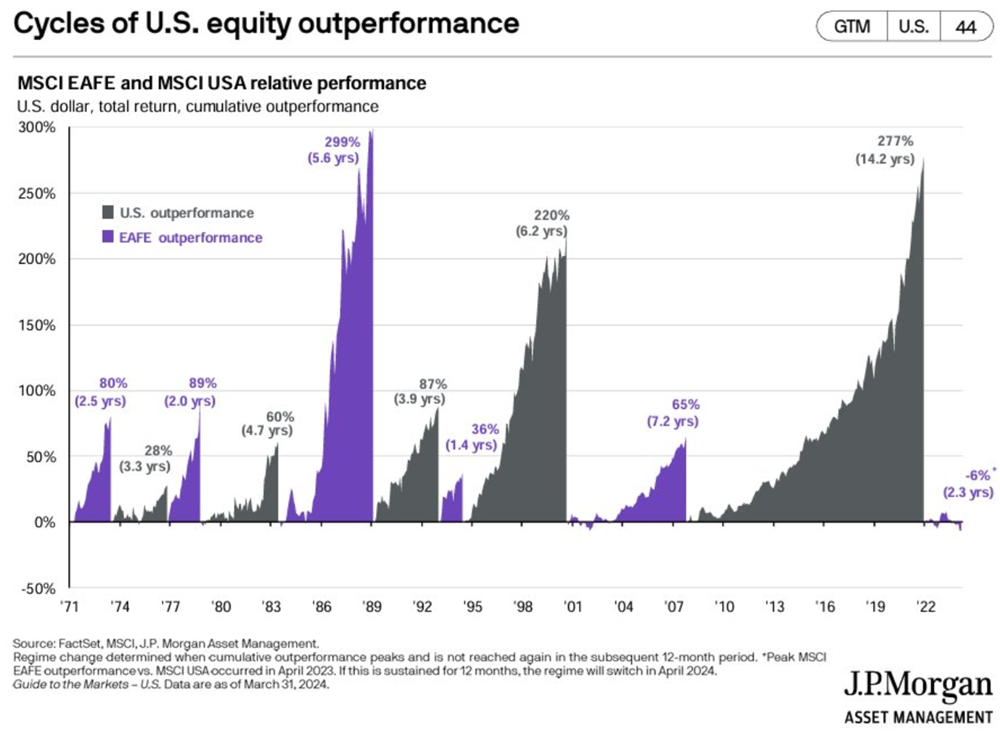

Investors love to extrapolate the recent past into the future. They see the US has outperformed the rest of the world for 15 years and assume that it will continue in future. And they’ll wrap a narrative around it by describing the US as ‘exceptional’ to assure themselves about the future.

Yet, the world isn’t static and that makes extrapolation inherently lazy. It’s amazing how many people think Trump was solely to blame for the recent market volatility when he was just the trigger for several broader changes taking place.

Zooming out on what’s really happening in markets and economies at present, there are four clear trends that are shaping investor portfolios, and are expected to last for a decade or more:

1. Politics is driving markets, not economics

The era of economic data driving markets is over. That was the world of globalization that reigned supreme for 40 years. It’s no more.

Governments and politicians have taken over. Trump didn’t start this because it’s been happening for some time.

It’s what investment strategist Russell Napier calls state-directed investment. Governments around the world are directing investments to purposes they want to achieve. Some are calling it re-industrialisation, industrial policy, friend-shoring, and de-risking. It all amounts to the same thing: Government-direct investment.

Trump is the obvious example of trying to force companies to invest money in the US. Yet, it was his predecessor, Joe Biden, who started this.

In Australia, the Labor Government has explicitly told the Future Fund to direct capital towards its priorities, including social housing and infrastructure.

And with debts levels at record highs around the globe, and markets often not providing finance at acceptable rates for Government-directed projects, national savings are being tapped. The next step with this is deliberately suppressing interest rates, which Trump is already trying to do.

With debt levels expected to increase from already exorbitant levels, politics will drive markets for the foreseeable future.

The problem for institutional investors is that they’ve never lived in a world where Governments influence markets to this degree and are largely unprepared for the changes afoot.

2. The 60/40 portfolio really is dead

The traditional 60% equities, 40% bonds portfolio is obsolete.

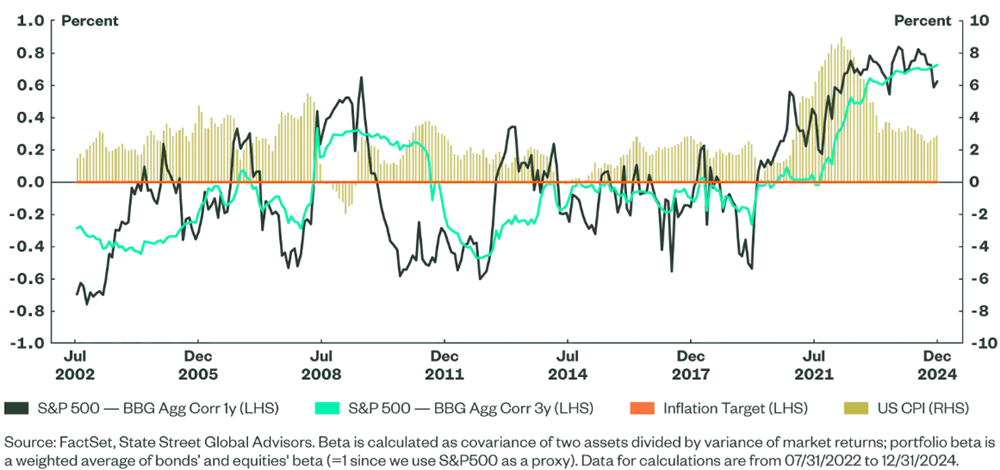

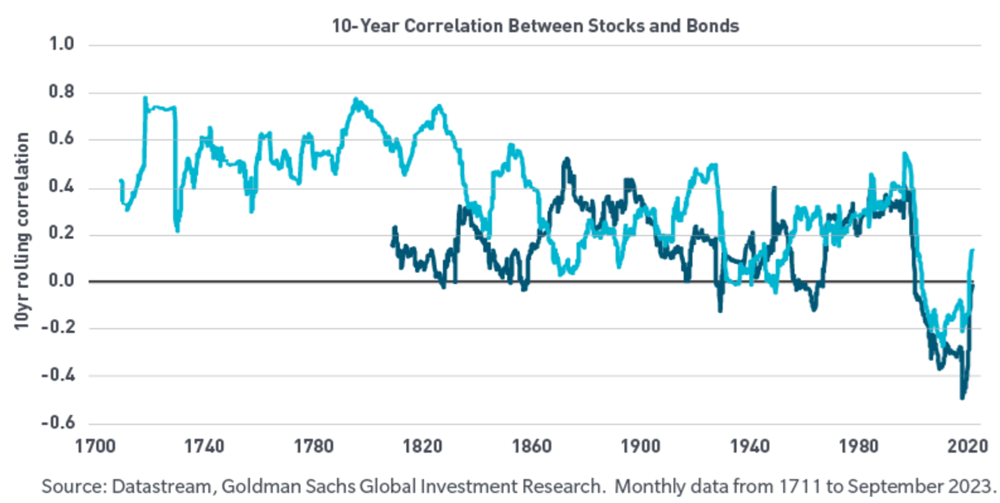

Since the early 1990s, when stocks went up, bonds usually went down, and vice versa. Bonds provided a nice hedge or ballast when sharp equity pullbacks took place.

Investor portfolios relied on this inverse correlation between stocks and bonds.

Yet, that correlation broke down in 2021-22 as both stocks and bonds tanked. And more recently following ‘Liberation Day’ in April, it broke down again. Yes, bonds fell less than stocks in the week after Trump’s tariffs first took effect, but they still went down.

60/40’s problems shouldn’t come as a surprise. First, it was always based on a false premise. It took the negative correlation from the early 1990s to 2021 as gospel when a longer thread of history told a different tale. The following chart from Goldman Sachs in 2023 shows that throughout most of history in the US and UK, there’s been a positive correlation between stocks and bonds ie. they’ve generally gone up together and down together. In other words, the 30 years to 2021 weren’t the norm; they were an anomaly.

Second, 60/40 ignored first principles: both stocks and bonds can be adversely impacted by excessive inflation and systemic risk. Excessive inflation puts upward pressure on bond yields, and consequently, tighter financial conditions can impact corporate profitability, creating conditions for a less favorable equity market. Systemic risk can have similar effects, as witnessed by the recent ‘Liberation Day’ events.

So, what are investors looking for diversification supposed to do? Well, stocks and bonds should remain the core of portfolios, with some potential nuances:

- Investors can consider having cash and short-term bonds alongside their intermediate- and longer-duration core bond holdings. Cash has diversified portfolios better than bonds in recent years, especially as interest rates have trended up.

- Rotating out of longer-duration bonds or funds and into intermediate- or short duration alternatives can reduce potential volatility during interest-rate spikes.

- Commodities are an option for smaller portion in portfolios. Correlations between stocks and commodities have trended down in recent years. The downside is the volatility in commodity returns.

- It’s worth considering gold. Gold isn’t an inflation hedge, as 2022 showed. However, it functions as crucial ‘insurance’ against systemic risks, especially amid growing concerns about currency devaluation, counterparty risk, and the integrity of the financial system itself.

- International stocks offer some diversification benefits though not a lot. The same goes for REITs.

- Private assets are more for the experienced investor than the novice. Their illiquidity makes them unsuitable for many portfolios.

3. Inflation may prove structural

As inflation subsides, the world’s central bankers are ready to pop open the champagne bottles. They should hold off for a few reasons.

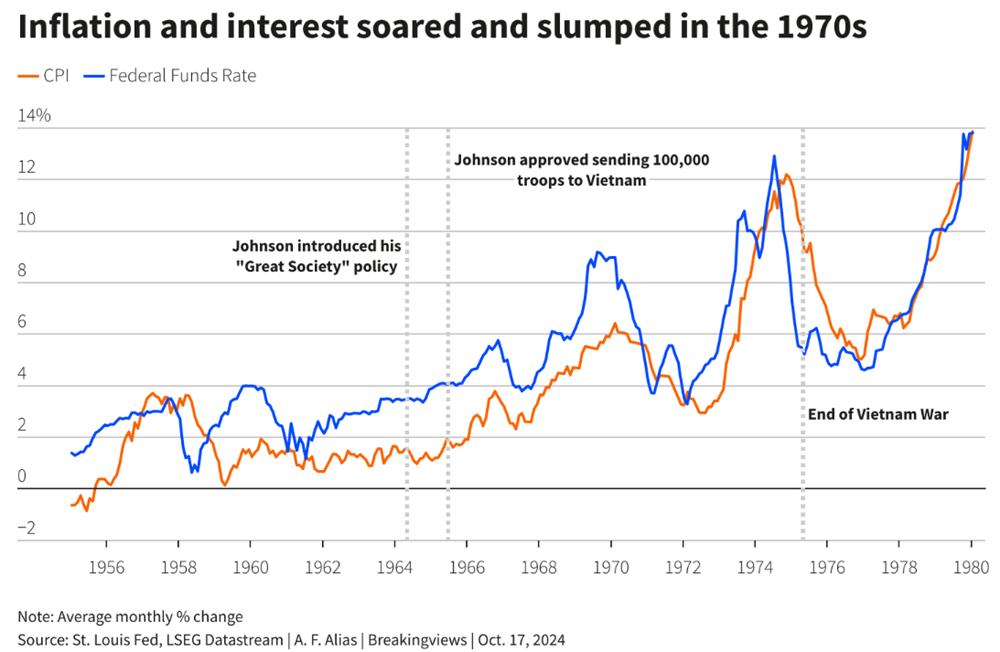

First, there’s a long history of central bankers declaring inflation dead before it rears its head again. The 1970s offer the latest example.

During the late 1960s, inflation rose as the ‘guns and butter’ policy of US President Lyndon Johnson took hold, with increased spending on the Vietnam War and social programs at home. The Fed raised rates to almost 10%, which led to a recession and a nasty pullback in the share market. Inflation fell to 2.7% in 1971.

Stocks mounted a stirring comeback, only to then be obliterated as inflation spiked again to 10% and rates were hiked to 13%. This resulted in a serious recession.

There were several factors behind the resurgence in inflation. In 1971, the dollar lost its monetary anchor after President Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold. At the same time, Nixon put pressure on Fed Chair Arthur Burns to pump up the U.S. economy during his successful 1972 re-election campaign. A year later, OPEC imposed an embargo on oil-importing countries that had supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The price of oil trebled. Finally, the Fed initially accommodated the energy crisis by cutting interest rates, which most economists at the time opposed.

This isn’t the 1970s though it should make you wary of those proclaiming an end to inflation.

That’s especially the case when the world’s Governments are loaded with debt and the most politically palatable way of reducing that debt is through inflation. Trump and Musk’s failed ‘DOGE’ experiments shows how hard it is for Governments to cut debt. Inflation is the easier route as it means borrowers like Governments can repay lenders with money that is worth less in terms of purchasing power, effectively lowering the real burden of the debt.

If right, there’s an argument for dedicated inflation-protected investments like commodities and inflation-protected bonds to become a permanent component of portfolios rather than a tactical allocation.

4. Stock markets outside the US offer upside on multiple fronts

After the recent comeback for US stocks, the S&P 500 is trading on more than a price-to-earnings ratio (PER) of more than 28x, 43% higher than the 17x average of the past 75 years.

Australia isn’t cheap either, on a trailing PER of 20x, with low single digit EPS growth expected over the next 12 months.

Other markets offer better value. Europe is on PER of 14x, and Governments there are significantly boosting infrastructure and defence spending, which should flow through to better economic growth, and higher corporate earnings. Investor Joachim Klement calculates that European spending could raise the EU’s annual trend growth rate over the next 10 years from 1.6%, the current OECD estimate, to levels like the 2.1% projected for the U.S.

Meanwhile, Japan’s market is trading at 13x PER, with continued benefits from a government-initiated corporate restructuring program.

Emerging markets are even cheaper at 12x PER, while China is at 11x. Yes, there are plenty of risks with these markets, though they've previously had sustained periods of significant outperformance.

And with Trump intent on depreciating the US dollar, there is currency appreciation potential for non-US markets too.

****

My article this week explores a new report which shows Sydney is likely to become the world's most expensive city for housing over the next year. Our other major cities aren't far behind, and the report is scathing of planning policies which have contributed to skyrocketing house prices both here and around the globe.

James Gruber

Also in this week's edition...

Last week, prominent property commentator Louis Christopher received an unusual email from his bank, CBA, demanding to know intimate details about his financial life and threatening to freeze his accounts if he didn't comply. Louis says the episode highlights a system which prioritises compliance over ethics and it signals a troubling future for community privacy.

It's nearing the end of the financial year, so those with SMSFs and other super funds should check the strategies available to them. Liam Shorte gives us a comprehensive 27-point checklist of the most important issues to address.

Despite a brief correction last month, Aussie bank share prices continue to defy widespread stockbroker doom and gloom. Hugh Dive casts his eye over recent bank results, and says there are good reasons why the Big Four may remain relative safe havens in a turbulent market.

Ophir Senior Portfolio Manager Andrew Mitchell sits down for an interview with Firstlinks and outlines how he’s managed the sharp turns in markets this year, his three key criteria for picking stocks, and why he thinks the Life360's growth story has a long way to run.

Our super funds have poured tens of billions into private assets in recent years on the premise that the asset class offers non-correlated returns with lower volatility. Fund manager and author Dan Rasmussen is highly sceptical of these claims. He suggests private equity, for example, primarily represents a big, risky bet on microcap companies.

A new study challenges the myth that Government spending is wasteful - public investment, especially outside the US, can yield major long-term economic gains, often outperforming private investment in driving GDP growth. Joachim Klement has more.

Two updates from Morningstar. Brian Colello looks at whether Nvidia is a buy, sell or hold going into earnings while Joseph Taylor asks Morningstar's energy analyst if markets are ignoring Santos' LNG potential.

Lastly, TD Epoch - a GSFM affiliate - has a whitepaper on the new global order and its implications for investors.

****

Weekend market update

In the US on Friday, the customary dip-buying impulse greeted a 1.5% opening drop on the S&P 500 following the latest round of Trump tariff rhetoric, with that strategy proving mostly successful once more as the broad average settled 0.7% to the red. Treasurys finished little changed with the 2-year yield remaining at an even 4% and the long bond ticking 5.04% from 5.05% Thursday, while WTI crude popped back towards US$62 a barrel and gold advanced another 2% to US$3,361 per ounce. Bitcoin pulled back to US$108,600 while the VIX settled at 22 and change, up two points on the session.

From AAP:

Australian shares finished the week higher, buoyed by a Reserve Bank interest rate cut but with global risks putting a lid on investor exuberance. On Friday the S&P/ASX200 rose 0.15% to 8,360.9, as the broader All Ordinaries lifted 0.18% to 8,586.7. The top 200 has made gains in five of the past six weeks and put the index within roughly 2.5% of its mid-February all-time peak.

Six of 11 local sectors traded higher on Friday, with energy stocks pushing 1% higher and tracking with a small uptick in oil prices.

The interest rate-sensitive sectors of financials (+0.5%), real estate (+0.8%) and IT stocks (+1.1%) also lifted the bourse as markets and economists narrowed bets on future RBA rate cuts.

All four big banks finished higher on Friday, helping lift the financial sector 0.5% for the day and almost 1% for the week.

Materials weighed on the exchange, down 0.7% on Friday as iron ore giants Rio Tinto (-1.6%) and Fortescue (-2.4%) sold off.

Uranium miners rallied on the back of US plans to boost nuclear reactor approvals and bolster fuel supply chains. Paladin Energy was the top 200's best performer, up 6.7% while lower cap uranium explorer Boss Energy jumped 12.1%.

Next week the Australian Bureau of Statistics will publish April consumer price index data, and the annual rate is expected to fall to 2.6% from 2.7%.

From Shane Oliver, AMP:

Global shares fell again over the last week after the huge rebound since the April lows left them overbought, worries about US public debt sustainability increased and as Trump threatened on Friday a 50% tariff on Europe from 1 June and a 25% tariff in imported smart phones by the end of June. For the week US shares fell 2.6%, Eurozone shares fell 1.3%, Japanese shares lost 1.6% and Chinese shares fell 0.2%. Australian shares were closed by the time of Trump’s latest tariff tantrum and so managed a 0.2% gain for the week helped by a dovish rate cut from the RBA with gains in telco, IT and financial shares more than offsetting falls in resources and retail stocks. Bond yields rose in the US, UK and Japan as investors refocussed on worries about public debt but were flat in Germany and fell in Australia helped by the RBA’s dovish guidance. The Australian dollar rose as the US dollar fell further, particularly after Trump’s latest tariff announcements highlighting that global investor confidence in the US is continuing to decline.

Trump’s latest tariff tantrum is not surprising – he threatened “take it leave it tariffs” of 25%, 30% of 50% on some surplus countries a week or so ago and the 25% on iPhones are likely just part of the sectoral tariffs still on the way. But if implemented they will push the average US tariff up from around 14% currently to around 18.5%. And they provide a reminder that the tariff war is far from over.

Trump’s policies are increasing the risk of a US debt crisis. Worries about the size of the US budget deficit and public debt have been around for decades with periodic flareups. In fact, the debt clock near Times Square first appeared in 1989. But because bond yields have been mostly low despite ever rising debt it hasn’t really been a problem. However, this has changed with: higher bond yields pushing Federal interest payments to a record 18% of tax revenue; debate in Congress about the OBBBA tax cut bill and its impact on debt; Moody’s downgrade of the US credit rating from AAA to Aa1; and concerns about US Treasuries’ safe haven status and US exceptionalism flowing from Trump’s chaos around tariffs, Fed independence, the rule of law, universities, etc. All of which is refocussing concern on ever rising US public debt. Out of interest, US gross public debt at around 125% of GDP is below that in Japan but above the average of advanced countries at 110% and well above that in Australia at 50% of GDP.

The return of the “bond vigilantes” resulting in even higher US bond yields could in turn put pressure on shares by further reducing the already low risk premium they offer over bonds.

Meanwhile there was good news in Australia with the RBA cutting rates again, from 4.1% to 3.85%, with more cuts ahead. The really good news is that it’s now less worried about inflation but the bad news is that it’s getting more worried about the growth outlook. The key messages from the May RBA meeting were that the risks to growth coming from Trump’s trade war are rising threatening higher unemployment, but with inflation back to target and forecast to remain there and monetary policy still being restrictive - with a cash rate of 3.85% against an average of neutral estimates around 2.8% - the RBA is able to cut interest rates and is likely to cut further.

Our base case is for the RBA to cut three more times to 3.1% by early next year with cuts in August, November and February.

Curated by James Gruber and Leisa Bell

Latest updates

PDF version of Firstlinks Newsletter

ASX Listed Bond and Hybrid rate sheet from NAB/nabtrade

LIC Monthly Report from Morningstar

Listed Investment Company (LIC) Indicative NTA Report from Bell Potter

Plus updates and announcements on the Sponsor Noticeboard on our website