The Weekend Edition includes a market update plus Morningstar adds links to two additional articles.

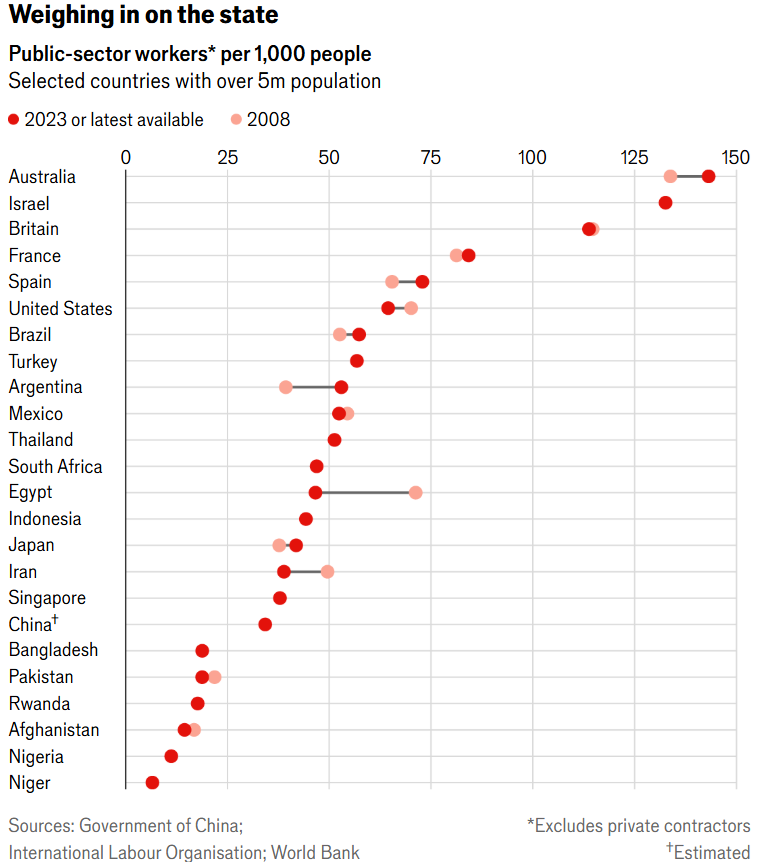

Recently, The Economist magazine wrote an article proclaiming that Australia had the most bloated government in the world. It produced this chart, with data from the International Labor Organisation, showing that adjusted for population, Australia has the largest public sector workforce, with 143 employees per 1,000 people – roughly 29% of the country’s workers.

The only problem? The numbers are almost certainly wrong.

Though comparing like-for-like public services is tricky, ABS figures show that Australia isn’t as big an outlier at The Economist claims.

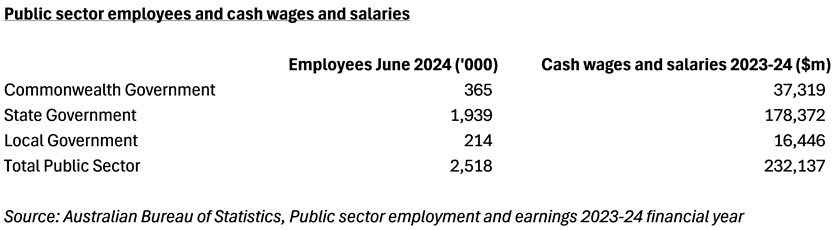

At June 2024, Australia had 2.51 million public sector employees out of a total population of 26.66 million - about 9% of the total population and 17% of the total workforce.

Though not as big an outlier, these figures suggest that Australia’s public service would still rank third on the above list of 178 countries.

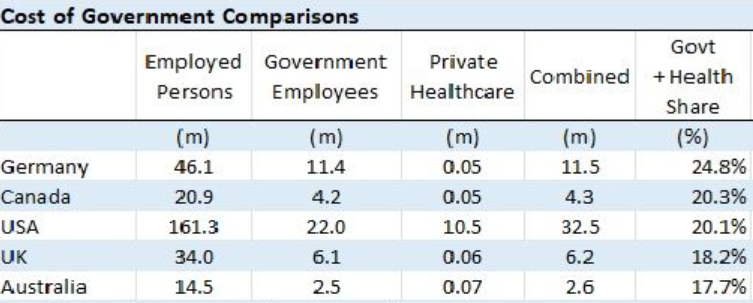

Yet, that may not tell the full story. Some think the numbers should adjust for things outsourced by governments such as healthcare. Here is how the figures versus four other countries look with that adjustment.

Source: Ivor Ries

I am not totally convinced this is a like-for-like comparison either, though it’s food for thought.

Labor loves Canberra

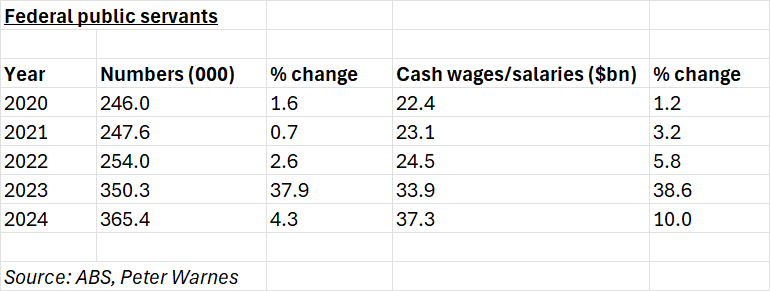

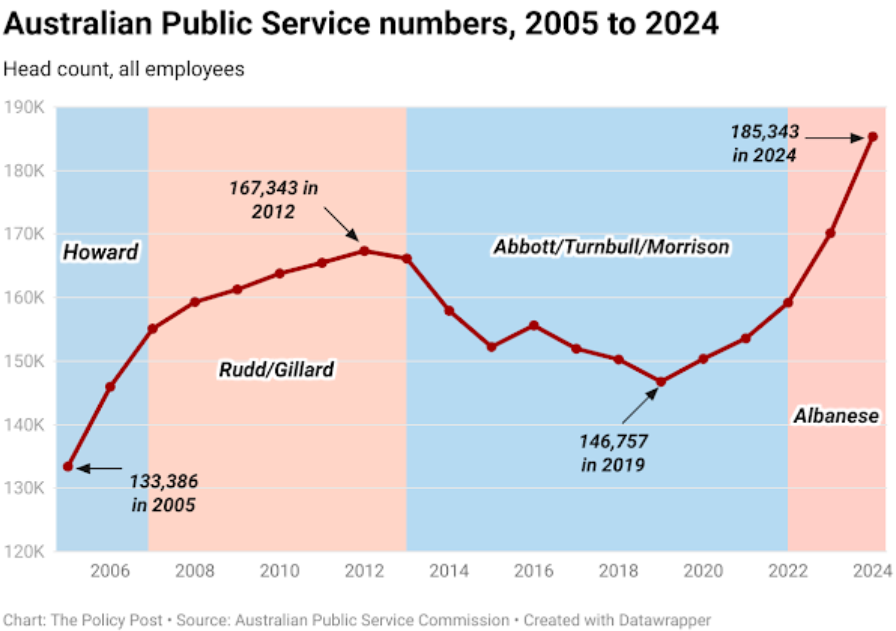

What’s clearer is that the Albanese Government has significantly boosted Commonwealth public service numbers since it came to power. For the two years to June 2024, federal public service figures, ex-defence, increased from 195,800 to 308,200, or by 57.4%. Total numbers including defence rose 44%. And Commonwealth public service wages lifted by $13 billion during that period.

Of the 101 Federal departments and agencies, just seven accounted for 63% of the new jobs added in the first two years of the Albanese government.

Defence led the way, with an extra 2,916 joining the department. Intriguingly, the number of uniformed ADF personnel fell over the two years, so all the jobs added were bureaucrats/administration.

NDIS and health were the other departments to have large increases in headcount.

How much of the increase can be justified?

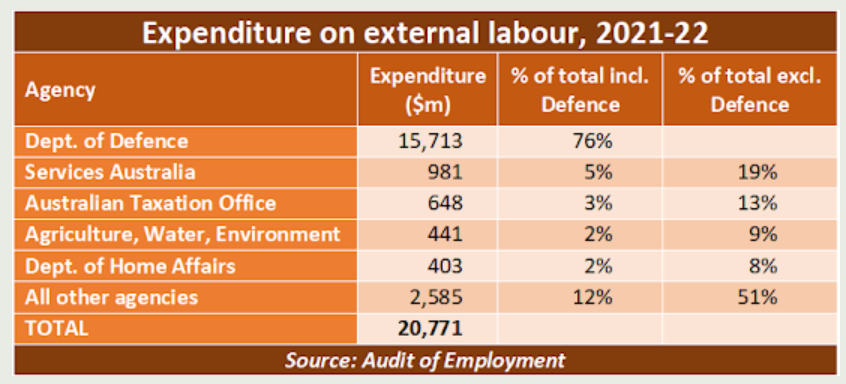

The Albanese government came into office claiming the previous Morrison government outsourced an exorbitant amount of public sector work to external consultants, costing taxpayers’ tens of billions a year. It intended to cut that waste and bring the work back to the Australian Public Service.

Labor had a point. In its final year in office, the Morrison government spent almost $21 billion on outsourcing public service functions. An audit commissioned by the new government found that external labour accounted for 53,911 full-time equivalent jobs in 2021-22. That ‘shadow’ workforce added 37% to the official public service.

I am sympathetic towards Labor’s suggestion that the Morrison government gutted the public service and outsourced the work to consultants who filled their pockets.

However, the truth is that the Commonwealth public service has been decimated of talent for decades. It started under Hawke and accelerated under John Howard when he appointed Max Moore Wilton, aka Max the Axe, as Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department. Power shifted from the public service to ministerial offices. That meant politicians no longer relied on independent advice and data from public service departments and agencies, but on the advice of their own staffers.

The problem with the Albanese Government is that it’s added public servants at a significantly faster rate than it’s cut outside consultants.

In recent budget papers, Labor said it had delivered on its commitment to reduce the public service’s reliance on consultants, with $3 billion in cost savings in the 2022-23 budget. And it would reduce consultant fees by a further $1 billion in 2024-2025.

That total of $4 billion in savings compares to total consultant fees of $20.7 billion in the last year of the Morrison government. An almost 20% cut in consultant fees is decent work.

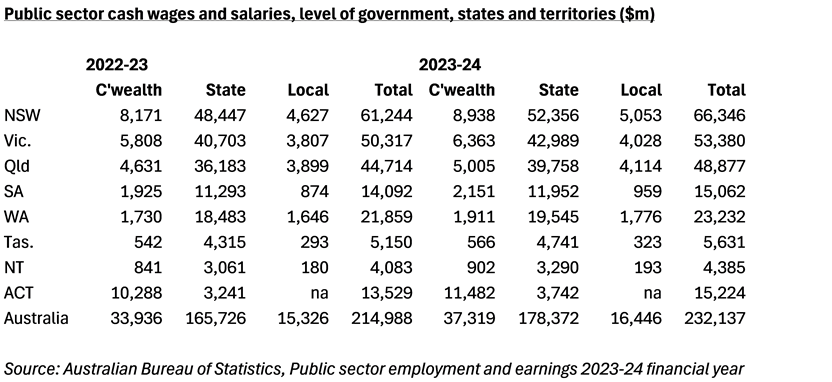

However, Labor has also hired new public servants to the tune of almost $13 billion during the same period. In other words, we’ve saved $4 billion in consultant fees by adding $13 billion in public sector wages.

The following chart shows that Labor isn’t just restoring the public sector workforce but adding to it.

Larger government bloat may be elsewhere

Context is important when considering public sector wages. They are relatively small fry when compared to total government spending. Australia spends $37 billion on Commonwealth government wages out of total budget spending of $762 billion, amounting to less than 5%.

If you want to deal with government waste at the federal level, then there are bigger issues to tackle.

And there may be a larger problem at the state government and council levels.

When plowing through the numbers, I was surprised by the employee and wage figures at these two tiers of government.

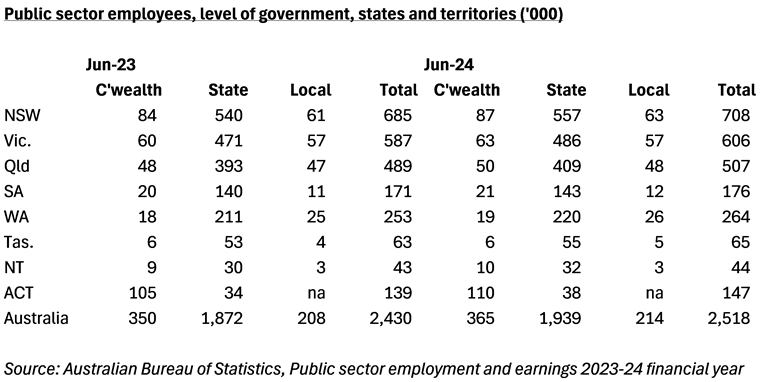

State Governments employ 1.94 million people at a cost of $178 billion, almost 5x the total wages of Commonwealth public servants. And local councils spend $16 billion on their employees.

About 1 in every 11 Queenslanders is a state government employee, and it’s 1 in 12 in New South Wales.

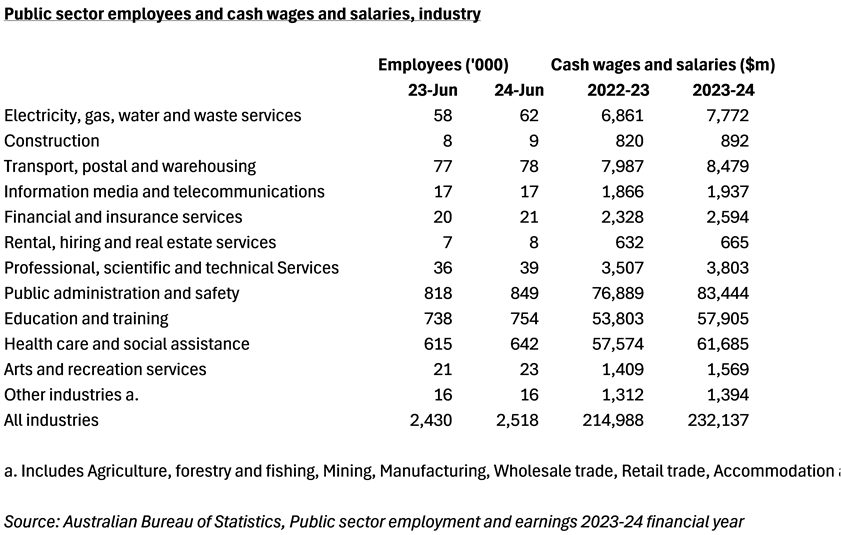

Breaking employee numbers (of Commonwealth, state and council) down by industry, about 1 in 3 public servants in Australia work in public administration and safety. Most of the rest are in education and healthcare.

I’m not sure we need 849,000 people working in public administration, costing $83 billion per year!

This data would suggest that state government and local councils may have a lot more fat to cut than the Commonwealth government.

James Gruber

Also in this week's edition...

Australian investors have been stumped by what's driven the extraordinary rise in CBA's share price over the past 18 months. Clime's John Abernethy says it's becoming clear that US fund managers are buying CBA to hedge against further falls in the US dollar and the potential for quantitative easing as America grapples with its huge budget deficit. He suggests the likelihood of QE and financial repression in the US has significant ramifications for Australia, beyond just CBA.

As markets reach record highs, exorbitant valuations and increasing concentration risk are leaving many investors with a quandary about what to do with their portfolios. Jamie Wickham advises on how to avoid knee jerk reactions and the best ways to position your portfolio for the future.

Soaring house prices are deepening Australia's cost of living crisis - and possibly distorting marriage decisions. New research by Stephen Whelan and Luke Hartigan links unexpected price changes to whether couples separate, stay, or silently struggle together.

Google has been one of the internet's poster children for disruption. Yet, AI is now threatening to diminish Google's lucrative search business - a case perhaps of the disruptor becoming the disrupted. Alex Pollack and Harry Morrow look into what Google is doing about it and whether it can reinvent itself to ward off competitors.

A new study has uncovered what many have long suspected about passive investing - that market ETFs and indexing don’t just mirror the market but shape it, often amplifying the rise of the largest firms. Larry Swedroe outlines the study and its implications for investors.

There's long been a debate about swapping property stamp duties for land taxes. Cameron Murray looks at the pros and cons of such a move, and whether it should be a priority to deal with the housing crisis.

Two highlights from Morningstar for you this weekend. Simonelle Mody highlights Morningstar's top picks in every ASX sector, while Brian Colello raises his fair value estimate for Nvidia.

Joe Wiggins says many of the behaviours that have made humans such a successful species also make it difficult for us to be good, long-term investors. He thinks the key to better decision making is to understand what makes us human and adapt.

Lastly, in this week's whitepaper, Fidelity provides its mid-year outlook on the opportunities and risks in markets.

****

Weekend market update

In the US, the summer Friday factor was in full effect as stocks slumbered through a flat, tight-range session, while two-year Treasurys recovered yesterday’s modest losses and the long bond finished virtually unchanged at 3.88% and 5%, respectively. WTI crude remained at US$66 a barrel, gold ticked higher to US$3,350 per ounce, bitcoin ebbed below US$117,000 and the VIX settled at 16 and change.

From AAP:

On Friday, the Australian share market finished at a record high for the third time this week, with every sector gaining ground in the bourse's biggest rally in three months. The benchmark S&P/ASX200 index gained 1.37% to 8,757.2, while the broader All Ordinaries rose 1.3% to 9,006.

The gains were the ASX200's biggest since a 4.5% rally on April 10 and the first time it has crossed 8,700.

For the week the index rose 3.39%, its best weekly performance since mid-December.

Every ASX sector finished in the green on Friday, led by health care, which climbed 2.5% as CSL added 3.6%.

Mesoblast rallied 34.6% to $2.41 after the Melbourne biotech company announced it had made $US13.2 million in sales, following the launch of its stem-cell treatment for a complication of bone marrow transplants in children in March.

BHP led the way for miners, climbing 3% to $40.29 after the Big Australian announced 2025 record hauls were on the cards for iron ore and copper.

Rio Tinto rose 1.8% to $113.11, while Fortescue lifted 0.5% to $17.

Graphite miner Syrah soared 25.9% to a two-month high of 36.5 cents after the US imposed steep tariffs on Chinese graphite imports, while peer Novonix added 16% to 54.5 cents.

The big four banks finished on the green, with CBA rising 0.9% to $182.46, Westpac adding 1.8% to $34.31, ANZ advancing 1.2% to $30.82 and NAB growing 1.3% to $39.19.

From Shane Oliver, AMP:

US and Australian shares pushed on to new record highs in the past week. Despite tariff uncertainty, the US share market was boosted by solid economic data and tech stocks getting a boost on indications Nvidia and others could resume chip sales to China. For the week the US share market rose 0.6%. Japanese shares also gained 0.6% and Chinese shares rose 1.1%, but Eurozone shares fell 0.2%. The strong US lead along with increased confidence that the RBA will cut rates in August, a strong production report from BHP and a bit of FOMO as the ASX 200 burst through 8700 saw the Australian share market rise 2.1% for the week led by IT, health, property, energy and telco shares. US, Japanese and Australian bond yields rose but they fell in Europe. Oil and gold prices fell but copper and iron ore prices rose. The $A fell on heightened expectations for RBA rate cuts and as the $US rose from oversold levels, but Bitcoin rose to a new record high.

In Australia, soft jobs data leaves the RBA on track to cut rates in August. With unemployment breaking to its highest since the pandemic and June jobs data showing broad based weakness it’s now hard to describe the labour market as tight. It also supports the view that the RBA should have cut this month. Our base case is for 0.25% rate cuts in August, November, February and May, but the softening jobs data suggests the risks may be skewed to faster easing with back-to-back cuts in August and September. June quarter inflation data on 30th July will be key. Meanwhile underlying US, UK and Canadian inflation data over the last week showing flat or a slight rise in core inflation to 2.9%, 3.7% and 3% respectively highlight that Australian underlying inflation at 2.4% compares well. The money market now sees a 98% chance of an August rate cut.

Tariff Man is back. Empowered by record high shares, still low unemployment and inflation, the passing of the tax cut bill, “victory” over Iran and frustration at the lack of trade deals Trump has escalated tariffs. While the delay to 1st August is good, in the last two weeks Trump has: announced reciprocal tariffs on 25 countries ranging from 20% to 50% including on Japan, Canada, Mexico and Europe; announced various sectoral tariffs including on copper and pharmaceuticals possibly from 1st August with more on the way; announced that other countries could face tariffs of 10-15%, although a week ago it was going to be 15-20%; and basically told us that there is no economic rational with Press Secretary Levitt saying he just looks at the global map to see where “they are ripping off the American people” with 50% on Brazil justified on the grounds that he didn’t like their previous president being prosecuted for inciting an insurrection.

The tariffs announced so far imply a spike in the average US tariff rate to around 21% from around 15% currently. Of course, the 1st August deadline could be extended again, and more trade deals may be announced. However, many countries seem reluctant to reach agreements with unknown sectoral tariffs yet to come and the deals reached so far are not so good. The deal with China is just a truce. The UK deal saw little in it for the UK. And those with Vietnam (which is yet to be confirmed by Vietnam!) and Indonesia are very lopsided with zero tariffs on US goods but 20% and 19% on goods from those countries going into the US. Ultimately, a combination of trade deals and Trump being forced to back down in the face of market volatility and or the economic impact are likely to see the tariffs settle back down around current levels, but this may take a while to become apparent. In the meantime, the risks to the economic outlook and hence for markets will likely build.

Curated by James Gruber and Leisa Bell

Latest updates

PDF version of Firstlinks Newsletter

ASX Listed Bond and Hybrid rate sheet from NAB/nabtrade

Monthly Bond and Hybrid updates from ASX

Plus updates and announcements on the Sponsor Noticeboard on our website