Billabong’s recent ‘big bath’ writedown marked yet another arguable example of hubris and investor loss by a major Australian company. It is worthwhile examining the investment merits of analysing balance sheets with the express intention of avoiding the permanent capital impairment that occurs with corporate writedowns.

Australia corporate graveyards are quite literally filled with the detritus of past attempts at greatness, where management’s actions exceeded their abilities and where ‘synergistic’ corporate kisses fell flat. For long-term investors in companies that suffer from being managed by such lauded corporate chieftains, time is an enemy that robs wealth. More importantly, clichés about investing for the long term are inappropriate at best and downright irresponsible at worst.

The dreaded ‘earnings update’ with a goodwill writedown

Companies regularly make announcements that may be hopeful and promotional or confessional and reluctant but it is the ‘earnings update’ containing a writedown that fires me up. This is where so many Australian companies have dashed their owner’s retirement dreams and hopes for financial independence.

In the 12 months to 30 June 2009 – admittedly the GFC was reaching its nadir - Australian companies wrote off, took a bath on, drew a line through or just plain old destroyed $47 billion dollars. And that was on top of $16 billion in writedowns the previous year. In 2010 Asciano took a $1.1 billion bath. In 2013 it was Billabong’s turn to make a writedown three times larger than its total market value. The result was affected by $867 million in significant items, including more than $604 million in writedowns in the value of goodwill, brands and other intangibles. It also included a $129 million writedown as a result of transactions involving US brand Nixon.

It’s the so-called ‘goodwill’ that I would like to examine today. A business is worth much more than its net tangible assets when it produces profits well in excess of market-wide rates of return. When this transpires the company is said to have economic goodwill.

A company’s book value is its net worth. Book value is made up of tangible assets and intangible assets. Tangible assets are physical and financial and include property, plant and equipment, inventory, cash, receivables and investments. Intangible assets aren’t physical or financial. These are trademarks, copyrights, franchises, patents and accounting goodwill.

Tangible and intangible assets

I have earned a bit of a reputation for warning investors about capital intensity, particularly with respect to investments in airlines. When it comes to physical assets, less is more. For a business to double sales and profits, there is frequently the requirement to increase the level of assets to produce those increased sales and profits. The higher the proportion of physical assets compared to sales that are required, the less cash flow available to the owner. This is the antithesis of the intangible-heavy business that continually produces profits without the need to spend money on maintenance, upgrades or replacements.

Take two companies Rich Pty Limited and Poor Pty Limited. Both companies earn a profit of $100,000. Rich Pty Limited has net assets of $1 million. Intangible assets, such as patents and a brand, represent $600,000 while physical assets including machinery running at full capacity and inventory represent $400,000. Poor Pty Limited also has a net worth of $1 million, but this time the intangible/intangible mix is reversed. Tangible assets are $800,000 and $200,000 is intangible.

Rich P/L is earning $100,000 from tangible assets of $400,000 and Poor P/L is earning $100,000 from tangible assets of $800,000. If both companies sought to double earnings, they might have to also double their investment in tangible assets. Rich P/L would have to invest another $400,000 to increase earnings by $100,000. Poor P/L would have to spend another $800,000.

For many investors a large proportion of physical assets – also reflected in a high Net Tangible Assets – was seen as a solid backstop in the event something catastrophic should befall a company. The opposite may be true. A high level of physical assets may be a drag on returns. Physical assets are only worth more if they can generate a higher rate of earnings. Any hope that they are worth more than their book value is based on the ability to sell them for more, and that, in turn, is dependent on either finding a ‘sucker’ to buy them or a buyer who can generate a much higher return and therefore justify the high price.

But while a high level of tangible assets producing low returns can suggest the tangible assets are overvalued, so too a high level of intangibles assets – particularly accounting goodwill – combined with low returns, can suggest a write down is in order.

Accounting goodwill is not economic goodwill

Back in December 2006, Toll announced the separation of its logistics business from its infrastructure and port assets. This was not a requirement of the ACCC who had asked Toll to merely divest 50% of its stake in Pacific Rail. Nevertheless, Asciano was born – its head was Mark Rowthorn, Paul Little’s deputy and son of former Toll chairman Peter Rowsthorn. Its balance sheet would be dominated by $4.5 billion of debt, $2.3 billion of property, plant and equipment (PP&E) and $4.2 billion of accounting goodwill – what I think the auditors should rename ‘Oops-I-paid-too-much’ before adding it to the balance sheet.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could all just add a few hundred million of goodwill to our own personal balance sheets before we headed down to the bank for a loan? You see, accounting goodwill is not economic goodwill.

Under the restructure Toll shareholders received a fully franked dividend that was compulsorily applied to subscribe for Asciano units. While this was another non-cash transaction it had the effect of ascribing a value. Asciano’s goodwill was inherited as part of the split that saw Toll shareholders retain one Toll share and receive an Asciano Stapled Security. The market (in its great wisdom) ascribed a value of $10.76 per security for Asciano on its debut, giving the company a market value of $6.8 billion. The net assets were $2.9 billion and net tangible assets were negative.

Would you pay $680,000 for a house and mortgage ‘package’ that comprised equity of $290,000? You would only if the profits the house was generating produced a decent return on the $680,000. Assuming an after tax return of, say 12%, the house would need to produce a profit after tax of $81,600. Turn the thousands into millions and that means, paying $6.8 billion you would need Asciano to produce an after tax profit of $816 million –a figure that has thus far not been achieved. Unsurprisingly, in the interim, Asciano had its own big bath writedown.

What’s happened since 2011?

With these ideas in mind, it may worth going back in time and looking at a list of companies that may have had very high levels of tangible assets compared to their profits. Indeed we may as well also throw in those companies that might have had highly valued intangible assets too. If they were generating low returns on these assets, as for example, Billabong and Fairfax have been recently, the auditors should arguably have taken a knife to their stated ‘book’ values. This is precisely what happened at Fairfax some time ago and more recently at Billabong.

But if high levels of intangibles are not written down by the auditors – even after years of generating mediocre returns – the market will often do the writing down for them. Either way, shareholders receive lousy returns.

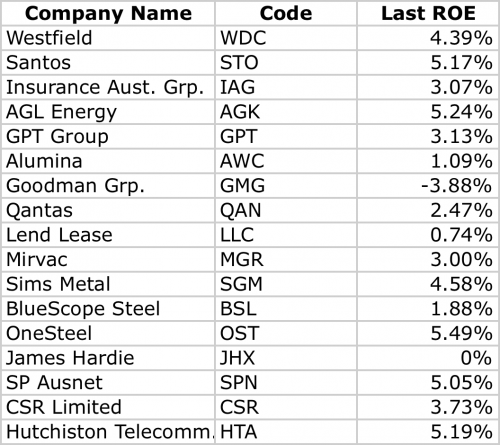

Let’s go back in time to 2011 and see what has happened since. Starting with the 156 companies with a market capitalisation of more than $1 billion, I ranked them by return on equity (return on book value) in ascending order and there were 49 companies generating returns less than a bank term deposit. The biggest 17 are presented below and I have excluded resource companies for while there are plenty that qualify, their returns are dependent on commodity prices.

Companies with either possible high levels of tangible assets or possibly overstated intangible assets carried on the balance sheet in 2011 include:

And what has happened to the value of a hypothetical portfolio invested in the above shares since? You will not be surprised that the market, in aggregate, has done a pretty good job on both an absolute and relative basis, of ‘writing them off’.

Roger Montgomery is the author of value investing best-seller, Value.able, and the Chief Investment Officer at The Montgomery Fund.