Job figures for September 2024 reveal that nearly all the additional hours worked over the past year have been in the non-market sector. Much of this has come from the ‘care economy’ - the fastest growing sector over the past decade, and the most common destination for workers switching industries. This has accelerated a long-standing trend in the Australian economy: its transition from goods production—particularly in agriculture and manufacturing—towards services - such as education, tourism, hospitality, and retail.

An ageing population that demands more healthcare, boosts to wages for aged care and child care workers, potential new investments in cheaper child care, and the continued growth of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) underpin projections that this shift will continue.

These projections of an ever-growing care economy often do not consider how the economy’s supply-side adjusts to accommodate it. Looking at employment shifts between sectors over the decade to 2022 can help unpack this.

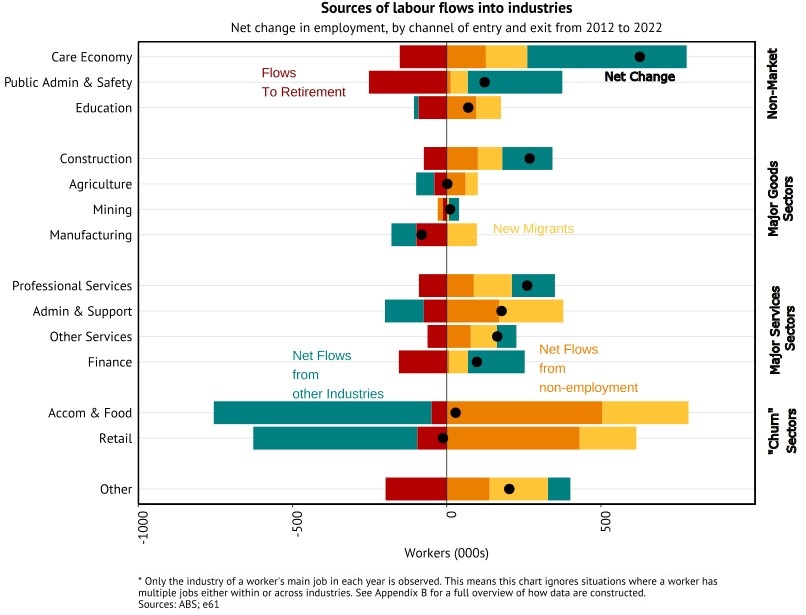

The shift towards the care economy is stark in these terms.

You can also see the clear trend away from employment in goods sectors. In fact, employment growth has been negative or small in most major goods industries – meaning they are falling as a share of the workforce. Many workers are leaving these sectors or retiring out of them. The one exception is construction, which has seen robust employment growth and stayed similar as a share of employment. Construction is an anomaly reflecting the high demand for homes and infrastructure running up against declining productivity, possibly in part due to zoning restrictions.

The care economy may look like a participant in the march towards a service-based economy. But the growth of the care economy differs from other service sectors in three key ways, with important economic implications.

First, while other service sectors have grown largely through new migrants and drawing workers from non-employment, the care economy has grown largely from workers switching in from work in other industries in the year prior. New research from e61 shows that over half of those switching into the care economy came from two major ‘churn industries’ – Accommodation & Food and Retail. Australians often use those industries as the first rung on the job ladder and the care economy has been capturing many of the subsequent steps.

Other significant contributors include Administration & Support, and Public Administration & Safety. This shift has caused market services' share of employment to decline for the first time in decades, dropping from 53% pre-pandemic to below 51% today.

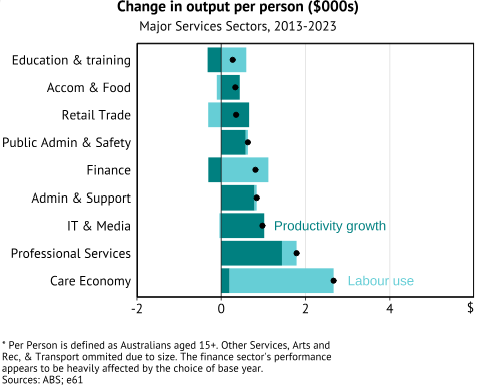

Second, the care economy has seen almost no measured productivity growth over the past decade, while most other service industries have shown solid gains. Although productivity growth is difficult to measure in the care economy (and appears to be underestimated in healthcare), a significant expansion in labour—reliably measured—has been essential to drive the growth of the care economy.

By contrast, other service industries have generally grown through productivity growth alone. This is true both in service industries which use technology heavily (such as IT and professional services – with finance being an exception) and those which are more people-driven. Looking at the industries supplying care economy workers: over the past decade, retail labour productivity is up 13%, accommodation & food by 18%, and administrative services by 23%.

However, this trend doesn't hold in the care economy, or for that matter, its companion “non-market” industry, education and training, where output has increased only by adding more workers, given productivity has been stagnant. The longstanding fear that 'services will slow productivity growth' is not being realised. Service sectors are not a monolith. Some service sectors – particularly in the `non-market’ sector - are experiencing weak productivity growth, but not all.

Third, policymakers may have to reconceptualise what productivity growth looks like on the ground. Productivity growth in market services over the past decade can be easy to visualise. Self-checkouts and restaurant QR codes, though sometimes inconvenient, reflect investments in labour-saving technology. Online retail can also improve efficiency in warehousing and inventory management. These changes – potentially also a response to a tight labour market and competition for workers from the care economy, where relative wages have risen materially over the past decade – mean firms can grow output with less labour use.

In contrast, imagining labour-saving productivity improvements in childcare or aged care is more difficult. In these sectors, preserving quality may be more important. It’s difficult to imagine a "self-checkout" equivalent for aged care. Instead, productivity growth might come from improving service quality without increasing worker numbers, as the Productivity Commission found in healthcare, rather than cutting labour while maintaining the same quality.

The expansion of the care economy represents the most profound structural change since the mining boom. It also offers the chance to ensure high-quality care for the most vulnerable—something a prosperous country like Australia can and should achieve. However, this brings fresh challenges, particularly in terms of labour demands and the impact on productivity growth both within the sector, and beyond.

Matthew Maltman is a Research Economist at the e61 institute, and previously worked at the Australian Productivity Commission.