It has been said that the only certainties in life are death and taxes. I’ll leave it to the accountants to discuss how taxes can be managed, but there is another problem with the uncertainty of death. No-one actually knows when it will happen. The problem with many financial plans is that they implicitly assume a particular age of death as if it is known in advance. There are several problems in this approach.

Average life expectancy is a poor measure

Consider ‘Helen’ who recently turned 66. Her life expectancy is currently another 24 years to age 90. This doesn’t mean that she will live to exactly age 90 or even close to that age. Around two-thirds of females her age will live to somewhere between 81 and approaching 99. In fact, there is only about a 5% chance that Helen’s or any particular 66-year-old female’s life will end in the year starting on her 90th birthday.

Life expectancy is a case where the average is a very weak predictor of individual (as opposed to group) outcomes.

The Actuaries Institute recently recommended that life expectancy results be shown in a way that includes the range of probable lifespans. So, what everyone should be thinking, and advisers should be saying to 66-year-old females, is vastly different from ‘your life expectancy is 90…’

A plan that only lasts up to the average life expectancy will disappoint every second retiree.

Exploring the distribution of actual lifespans

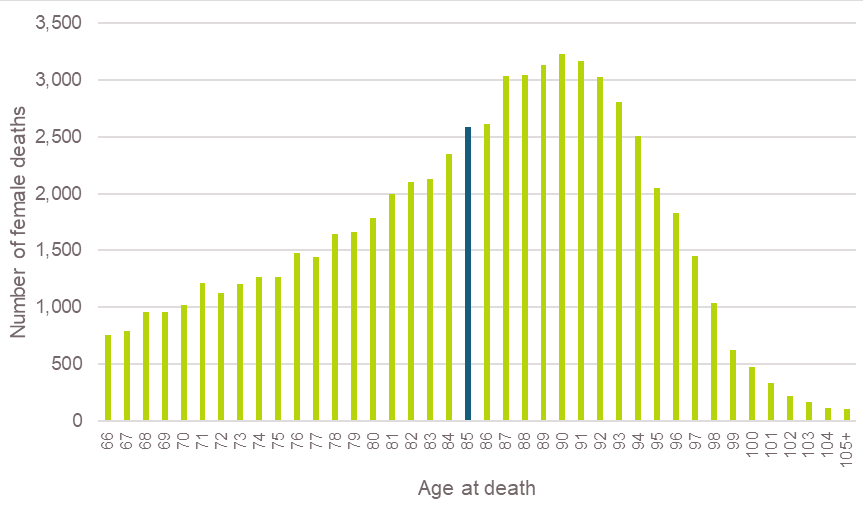

The distribution of actual lifespans can be seen in Figure 1 below, which shows the age of death for older Australians in 2018. The data in the chart are historical (i.e. the peak of the histogram reflects people who were 66 back in 1994) and don’t capture the mortality trend for younger retirees but are still indicative. The highest point (at age 90) still represents less than 5% of over-66s, while the weighted average was only 85.

Figure 1: Actual age of death for Australian females aged over 66, 2018

Source: ABS Cat 3302.0

The charts shows how unhelpful life expectancy figures are in predicting an individual lifespan. Predictions of life expectancies bely a broad range of actual outcomes. With at best a 5% success rate, a plan that relies on a certain age at death, even if it is the correct life expectancy, has an almost immaterial chance of success. The projected lifespan will either be too short and leave a retiree to live only on the age pension or it will be too long and leave a lot of unspent wealth.

Another takeaway on the difference between actual lifespans and predicted life expectancies is that the most common age of death (or statistical mode) in 2018 was 90 for females. If the life expectancies being used in financial planning tools aren’t at least as high as this, then there is an assumption that life expectancies will go down. This would potentially let down retirees and for advisers, nearly all of their clients.

The potential issues are even larger for an advice practice with say 1,000 retired clients. The distribution of their lifespans would look a lot like the chart above. For smaller shops, with only four of five advisers, the client mix might not match the pattern exactly, but it will still be close. The key point is that many clients will need a plan that extends beyond average life expectancy.

Life expectancy of couples

A significant majority (nearly 70%) of people enter retirement as a couple, and the life expectancy of a couple is actually greater than their individual life expectancies. This is because a couple is a pool of two people, rather than one. This increases the risk that one of them will live longer than their combined individual life expectancies. This needs to be factored into retirement income planning.

Wealthier people live longer

There is a well-known link between wealth and life expectancy. People with more wealth tend to have better health and live longer. Accurium studied the mortality of SMSF trustees. They found that SMSF trustees (aged between 55 and 75 in their study) were materially less likely to die than the rest of the population. This means that their life expectancy is longer than the average population.

Even the average client of a financial adviser is likely to be wealthier, and possibly better educated than the average person. As a result, they will also have a higher life expectancy than average. For an adviser, there is a ‘selection bias’ in that the people with enough wealth to seek financial advice are likely to be people who live longer than average.

Understanding longevity uncertainty

The uncertainty around life expectancy is significant. Most investors are aware that equity markets can be volatile. What they probably don’t realise is that the variation around life expectancy is about the same as 10-year equity market returns. For a retiree, the uncertainty around how long they will live is as big as the uncertainty around average real Australian equity returns over successive 10-year periods from 1900 to 1910 and so on through to 2010 (based on Morningstar data).

A longevity checklist

There are a lot of issues for the average retiree to understand. For both retirees and advisers, it is important that longevity risks are understood. The following checklist could help in that process:

- Use up-to-date life tables - currently 2015-17 at aga.gov.au

- Use an appropriate mortality improvement table – 25-year improvements (explained in 2015-17 life tables) which are the ‘most optimistic’ and hence safest to use

- Never use a ‘from birth’ life expectancy. They are not relevant to retirees

- Build in a margin of error – 50% of people will live longer than average life expectancies

- Use a range when thinking about how long you might live

- Remember the gender differences and plan for them

- Remember the ‘joint lives’ issue – the age of the second death is potentially longer than each single life expectancy.

Aaron Minney is Head of Retirement Income Research at Challenger Limited. This article is for general educational purposes and does not consider the specific circumstances of any individual.