The global stock market looks stretched at first glance—but the story is more nuanced once you dig beneath the surface. The perception of lofty valuations is being driven almost entirely by the very largest companies, while much of the rest of the market is priced closer to historical norms.

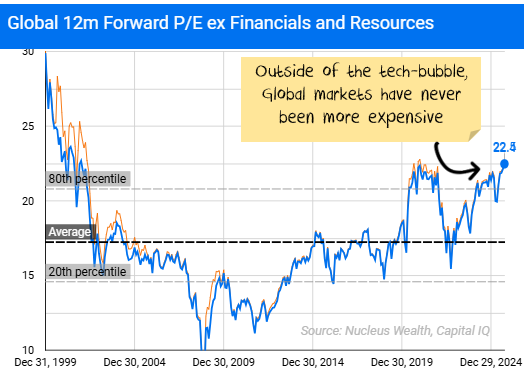

Why the market looks expensive

Headline market valuations, particularly when measured by forward price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, suggest that stocks are expensive. However, when we separate companies into groups based on their size, it becomes clear that the top names—typically high-growth, mega-cap technology and consumer firms—are disproportionately pulling averages higher.

These giants command premium multiples that skew weighted averages upward, making the entire market look pricier than it really is.

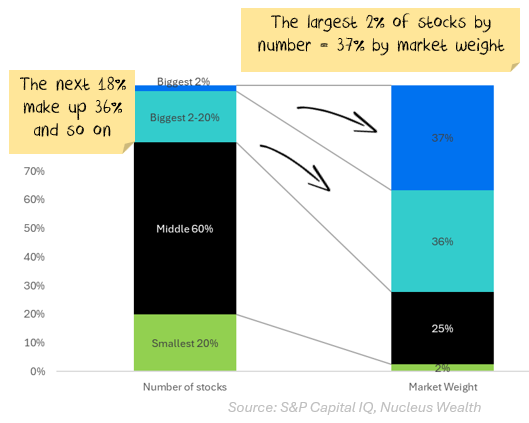

First, a quick definition. I'm looking at the top 1,500 developed market stocks globally - about 80% of the market capitalisation of all stock markets. Then, I've created 4 buckets of stocks:

When you look at it this way, the problem seems like it is limited to just a handful of stocks:

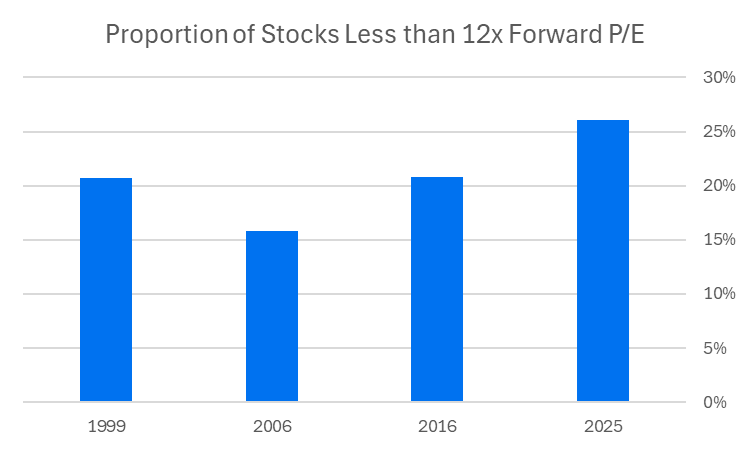

And if you want to get fancy with stats, you can see that there are more stocks with a low ratio (12x forward price/earnings) today than there were in a more moderately priced 2016, or before bubbles burst in 1999 or 2006:

Could there be an alternative narrative?

Even in a rational world, the stocks that are expected to grow faster should have a higher price/earnings ratio.

What would a world look like if it just happened that the largest stocks also came from higher price/earnings sectors, and had the best growth outlook?

The answer: a lot like it does today...

Which doesn't say the valuations are right, but it does colour the lens through which we should be looking at them.

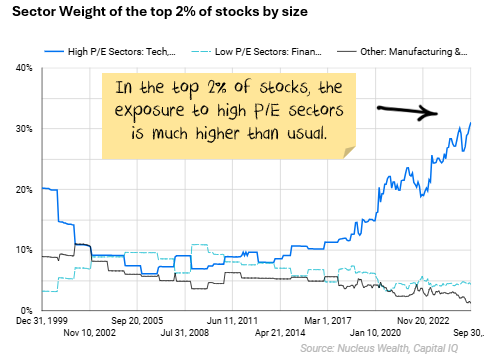

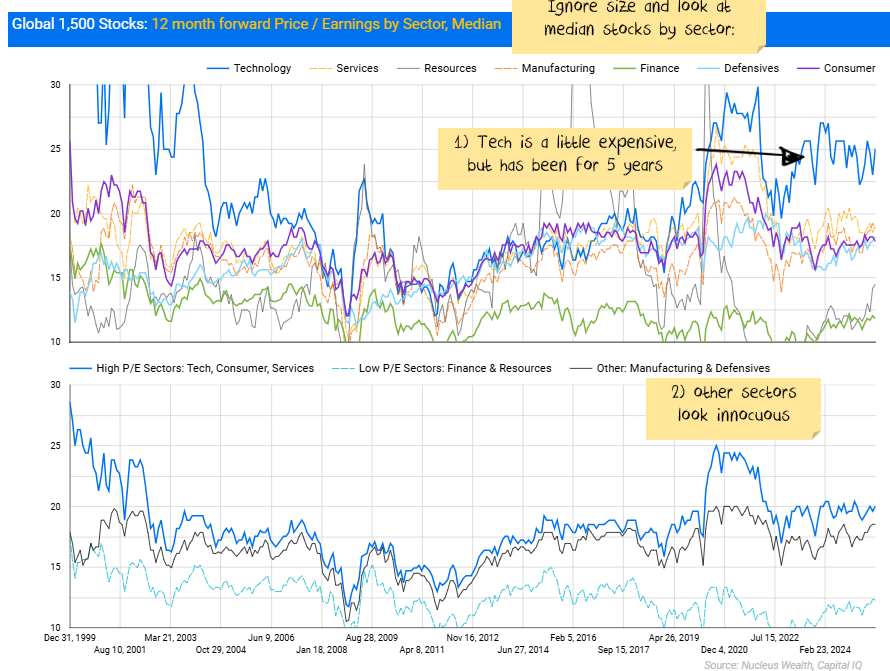

Sector composition matters

Some of the difference is just the sectors. There are some sectors which are traditionally low price/earnings because the earnings are riskier, or the leverage is much higher. Banks and resources usually fall into that camp.

Some sectors are traditionally higher price/earnings. Usually because of more stable earnings, lower capital expenditure or lower leverage. Consumer, services or technology stocks often fall into this category.

To put it another way, if the top 2% of stocks (by size) had lots of financials, then you would expect a lower P/E than if they were all services or tech stocks. Which largely correlates with valuation moves.

If you ignore size and just look at medians, most sectors do not look expensive:

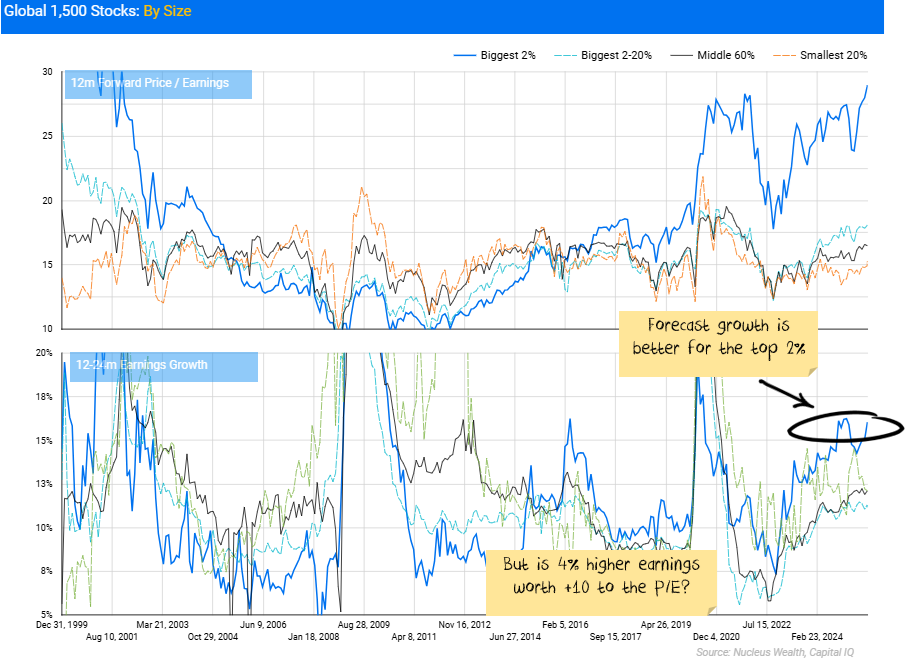

Growth expectations: Reality vs. hype

So, is the difference just that the largest stocks also happen to be the highest growth?

Certainly, on forecasts, that is the case. But not by that much:

A rational case for today's valuations

Say the US goes into a reasonably sized economic slowdown:

- Stocks exposed to the consumer get hit, and most ‘moderately priced’ sectors that are not tech see earnings downgrades. Stock prices also fall.

- The Fed cuts interest rates

- The tech sector keeps spending on AI and data centers, funded by lower interest rates and fear of falling behind competitors. The slow down in other sectors reduces the competition for construction resources.

- Capital markets stay open, we see a rash of AI IPOs, most of which gets plowed back into buying stuff from other tech companies

- Under Trump there is little anti-trust activity in the AI sector, most of the benefits accrue to the largest companies

- Large tech sector earnings increase

Let us talk valuation. What would the growth differential need to be to justify paying 28x today for a large tech stock vs 16x for other companies?

Say we are talking net present value in broad terms. A discount rate of 11%, ten years of tech stocks growing faster than other stocks, then long term earnings growth of 5% for all stocks.

The answer? About 9%. i.e. if tech stocks can grow at say 12% p.a. while the rest of the market does 3% for 10 years then it would be rational to pay 28x for large tech stocks vs 16x for other stocks.

Maybe you value the low debt levels, high and stable margins that the tech sector brings. Then, you could easily argue that a 5-6% difference in growth would be enough.

Net effect

Stock markets are not cheap at an aggregate level. But, within the sectors and growth profiles there might be more rationality in the pricing than might first appear.

It might look safer in the lower-priced sectors, but there is a lot more earnings risk in those stocks from tariffs and general Trump driven-disruption.

Tech stocks are not cheap. But for most of the largest ones, the earnings are high quality, not volatile and margins are wide.

I'm not entirely convinced. But I'm enough convinced to be mostly invested at the moment. And I am convinced that the right lens is to consider how much AI stock earnings will exceed non-AI stocks, and then work out how much more should you pay for that growth.

Damien Klassen is the Chief Investment Officer at Nucleus Wealth. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.