Tennis staged its first ‘open’ tournament in 1968, when the British Hard Courts were staged at Bournemouth. The open tag meant professionals were welcome to play in national tournaments including Grand Slams, which until then were restricted to amateurs. For more than five decades, prestigious tennis tournaments welcomed players from any country.

The globalisation trend is over

No more. This year’s Wimbledon has banned players from Belarus and Russia. Their offence? Russia attacked Ukraine, and Belarus was a base for some of the Russian invaders. While no one will call it the Wimbledon Almost-Open, the fracturing in the global nature of sport competitions reminds how the era of hyperglobalisation is over. Hindering the movement across borders of commodities, components, culture, goods, ideas, money, people and services appears an irreversible trend.

The most recent impetus is that war between Russia and Ukraine has elevated a strategy known as geoeconomics, when economic and financial tools are used to promote national political goals. About 30 Western countries are choking Russia with the most draconian financial sanctions and export controls ever imposed on a leading power. The freezing of half of Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves is such a breach of trust and property rights it portends an unfixable tear in the US-dollar-dominated global financial system.

Europe’s need to move away from Russian hydrocarbons shows how free trade only happens when the world feels secure.

The pandemic was the previous setback to globalisation because it showed that producing essential goods far away from where they are needed is too risky, no matter the cost savings from cheap labour.

A change in the emerging market winners

An initial impediment in advanced countries for the globalisation that occurred from the 1980s was the cultural pushback against the loss of local political accountability, and the political reaction from those who lost jobs as manufacturing shifted abroad. The winners were the billion-plus people in emerging countries who soared out of poverty. These countries, foremost China, expanded in political muscle.

The post-hyperglobalisation era too will come with winners and losers and economic and political consequences. Winners will include emerging countries close to, and friendly with, Western powers. Countries such as Mexico stand to gain from any ‘near-shoring’, or ‘regionalisation’, of production. US allies stand to gain from “friend-shoring”. Other victors will include Western businesses producing essential items deserving of protection.

Unworthy winners will be companies of lesser offerings that are talented at ‘rent seeking’ – manipulating policymakers to boost their profits. Losers will include emerging countries that miss out on investment that would have created jobs and wealth. A notable loser might be China.

Other also-rans will be multinationals that seek customers across the globe and companies that had production arrangements that spanned the world. The ‘splinternet’ will be starker as governments block access, protect local data and toughen cybersecurity.

Potential to lower living standards for all

For consumers, production ‘misallocated’ to higher-cost locations, steeper tariffs and rent seeking spell lower living standards.

The economic consequences of ‘slowbalisation’ are faster inflation (at least initially) and slower growth. Emerging countries will miss out on know-how and an opportunity to build wealth through exporting. Barriers preventing investment in emerging countries, however, could give workers in advanced countries greater bargaining power and a greater share of national income.

While inequality might decline, there might be less wealth to fight over because profits might be lower in a more-fenced world. Returns on capital might be reduced because protectionism will inhibit economies of scale and companies will carry larger inventories. Reduced profits spell lower corporate tax takes. Hindered capital flows suggest investors might have to stomach lower returns from accessible investments.

Politically the world is likely to split. A US-led group will favour a rules-based order among themselves. A China-led bunch will group authoritarian countries extolling a power-based world. The Chinese-US “lose-lose tech war” will create a schism across tech platforms and ‘data sovereignty’, and will mean less innovation. A split world means less international cooperation on global challenges such as climate change. Within countries, globalists will battle patriots for political power.

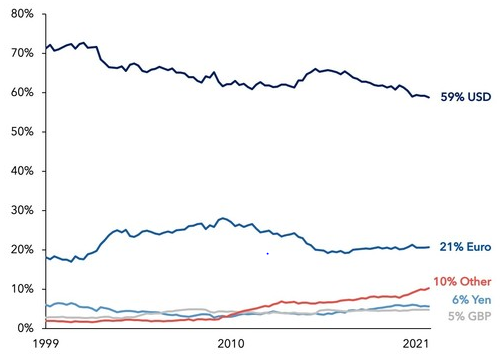

What might remain the same? The US currency is bound to stay the world’s reserve currency because it lacks a credible rival, even as US opponents seek alternatives.

Currency composition of foreign exchange reserves since 1999

IMF. June 2022

To be determined? The cleverness of policymakers. The West would best avoid a permanent stand-off against a rival bloc and advanced countries might need to rejig the international financial system for a multipolar world to support emerging countries. But even if policymakers prove sound, the era of inefficient globalisation heralds a poorer future than otherwise.

But with some qualifications

Globalisation always proceeded at different speeds and security considerations were never ignored. Globalisation is so layered it’s hard to generalise about its direction or pace. Any retreat from the recent pace of globalisation has natural limits, as does the China-US split, because too much is intertwined and too many vested interests favour the status quo. The internet might make people feel they are as tied to a globalised world as before.

People and businesses will be connected but not like they were. Their state of mind has turned away from the hyperglobalisation that, for all its drawbacks, enriched the world. A more-stunted form of globalisation points to less prosperous times. Even winning Wimbledon will lose a little of its glamour.

Michael Collins is an Investment Specialist at Magellan Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is for general information purposes only, not investment advice. For the full version of this article and to view sources, go to: magellangroup.com.au/insights.

For more articles and papers from Magellan, please click here.