Baron Rothschild is credited with saying that "the time to buy is when there's blood in the streets." Implicit in this statement is that markets are mean reverting and periods of extreme negative returns are not likely to be sustained. Put simply, when everyone is selling it often represents an opportunity to achieve superior future returns.

Of course being a contrarian is not easy and goes against the natural bias of human behaviour. When returns are negative there is a natural bias to shy away from investing. But this is precisely the time to invest to achieve above average nominal returns. Conversely when markets are running hot everyone wants to be greedy.

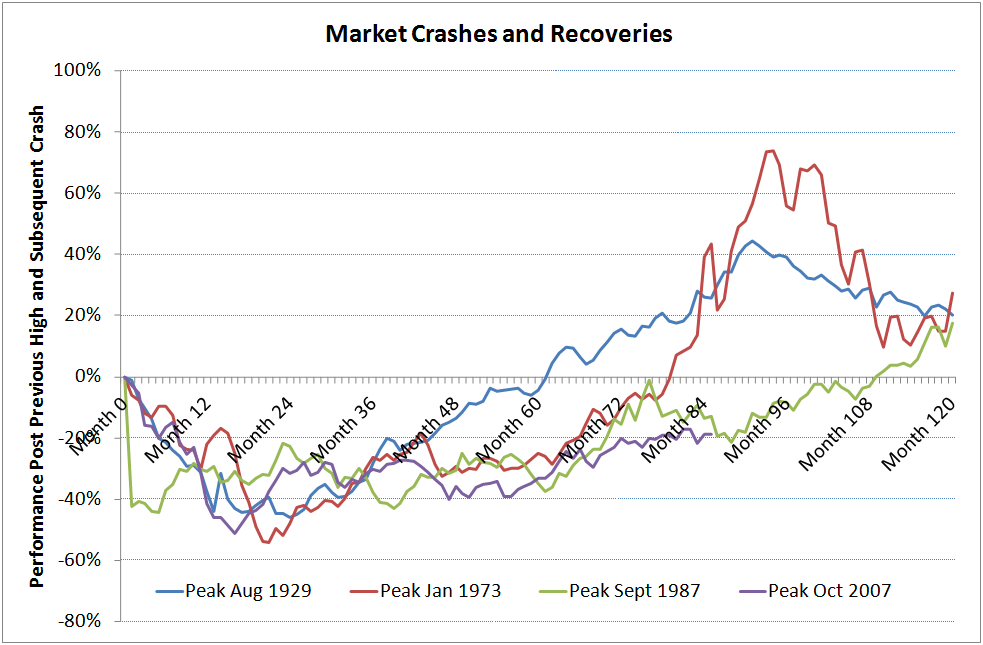

In early 2012 Alan Kohler on the ABC News commented that the current recovery was the worst on record, including the crash of 1929, the inflation-induced recession of 1973 and the bubble of 1987, and used Chart 1 to demonstrate (which has been updated to October 2014). But markets do not stay pessimistic indefinitely (with some exceptions such as the Japanese market). Nor do markets stay “irrationally exuberant”, to quote Greenspan.

Chart 1: Market crashes and recoveries

Source: Historical records based on monthly time series of the combined price history of the Sydney Stock Exchange and the Melbourne Stock Exchange from 1900 to 1970 and the ASX All Ordinaries Price Index from Dec 1970 to Oct 2014.

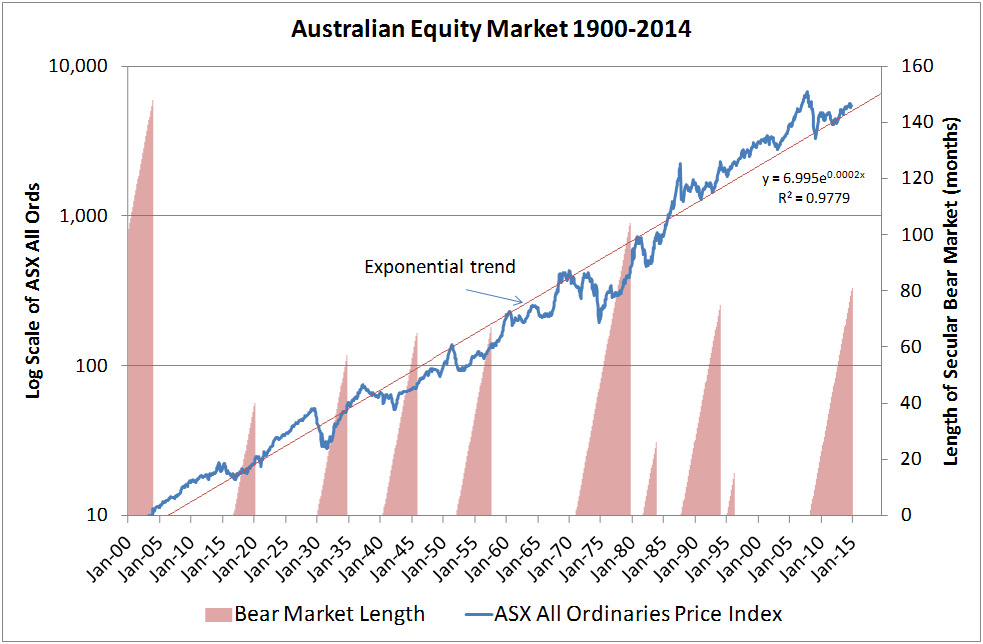

Chart 2: Australian equity market and length of bear markets

Bear market is measured as a 20% decline from the market high and lasts until previous high is surpassed.

Since 1900 the Australian equity market has returned 5.76% pa (geometric average, excluding dividends and before inflation, to end of October 2014). In the short term markets are random, but over the long term markets mean revert to the long term average.

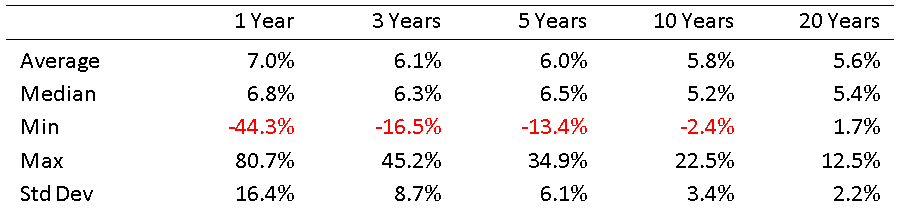

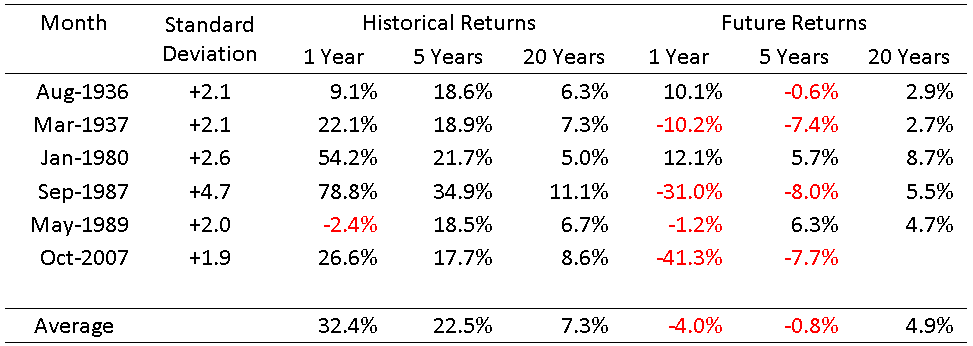

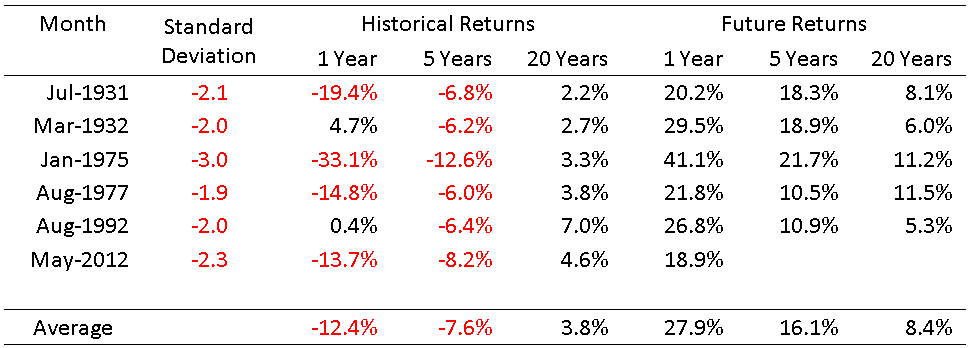

Table 1: Historical Returns 1900 to 2014

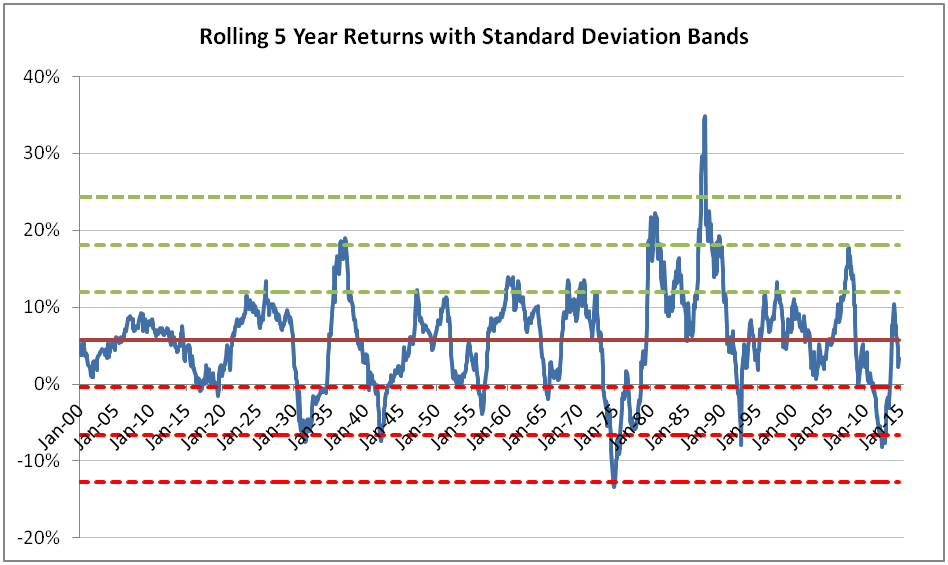

The mean reversion of the Australian market can be illustrated by charting rolling five year returns (Chart 3). For simplicity standard deviation bands have been included around the long term mean of 5.76% pa. Some 68% of all returns will reside within a standard deviation of +1 and -1, and 95% of returns reside within a standard deviation of +2 and -2.

Chart 3: Rolling 5 year Australian market price index returns

Importantly, returns significantly above or below the long term average are simply unsustainable.

The peak of 1987 was more than 4 standard deviations away from the long term mean. Statistically the chance of this occurring is 0.02%. The returns into 2007 were two standard scores above the mean. The crash of 1929, World War Two and the 1992 recession saw five year returns more than two standard deviations away from the mean and the inflation led recession of 1973 saw returns more than 3 standard deviations from the mean. Even May of 2012 saw five year returns almost two standard deviations away from the mean.

Table 2: Historical 5 Year Standard Deviations greater than +2

Table 3: Historical 5 Year Standard Deviations less than -2

Of course, not all companies recover from tough times. This analysis focusses on the broad market, but not all individual companies revert to a mean. Some disappear forever!

Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate that when historical returns reach positive/negative extremes, future returns have a high probability of being significantly less than/greater than the long term average. For example, in Table 2, where the market is more than two standard deviations above its long term mean, such that historical returns have been good, the future returns from that point have been poor. Conversely, in Table 3, where the market is below its long term mean, the future returns from that point have been good.

If history is a guide one would expect future returns from the low of May 2012 to be above the long term average. This does not mean the markets won’t be volatile as they never move in straight lines – and markets can remain subdued for periods much longer than expected (for example the Japanese stock market). But it can give one a glimpse of where the market may be headed.

Robert Stewart is a Director of Sandgreen Pty Ltd, former Head of Challenger Howard Mortgage Fund and Head of Index Funds at Colonial First State Global Asset Management. This article is for general information and is not personal financial advice. Readers should seek their own professional advice.