One of the big challenges we see for investors today is the disconnect between the investment returns that have been realised over the past few years, and the likely investment returns that await us in the years ahead.

At face value this disconnect is easily understood. Recent history has been spectacularly good for most asset classes. Stock, bond, and property markets - three investment classes that dominate most portfolios - have all delivered recent returns that are well above their long-run averages. It has been quite some time since the average long-term investor has suffered any real financial pain.

While it is true that the pandemic caused a severe market correction, global equity markets had recovered to their all-time high within six months of this event. That feat took three years following the GFC, or five years following the ‘dot-com’ crash.

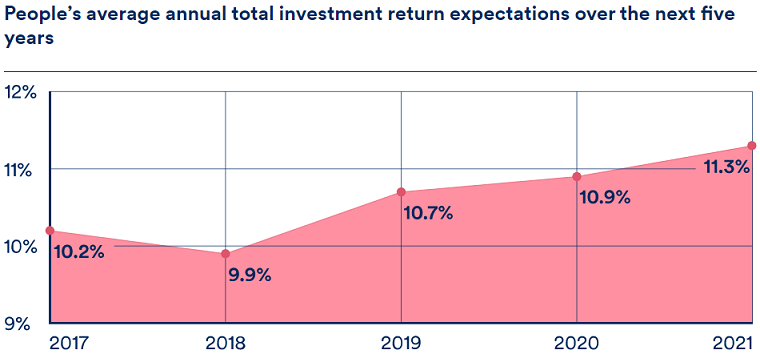

With returns plentiful and perception of risks low, it is understandable that investors’ expectations have been steadily rising. The 2021 ‘Global Investors Study’ of over 23,000 investors in 32 locations by Schroders highlighted that its respondents expected average annual investment return of 11.3% over the next five years, a figure that has increased in each of the past three years Schroders has run this survey. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study shows that people’s return expectations are at their highest in the countries that have enjoyed the strongest local market gains in recent years.

Source: Schroders Global Investor Study 2021

Try as we might, we are all emotional actors. Recent investment returns are not a particularly robust platform to base future return expectations on. Worse, the driving force behind these recent stellar returns has been a been a period of relentless falls in interest rates all around the world. This has provided a one-time boost to most asset classes, as lower discount rates have reset asset valuations higher.

Lower interest rates mean higher asset prices

It is a truism that as the cost of money falls, the value of assets simultaneously rises. For example, lower mortgage rates provide home buyers with the ability to pay higher prices for houses. This same principle applies across all asset classes. Long duration (or length) assets benefit from this the most, as they have the greatest sensitivity to the cost of money.

But higher asset prices also mean lower long-term returns.

Finance theory says that the return from an investment should be anchored to the return received from holding the current ‘risk-free’ rate such as a term deposit account - essentially zero return today. With more risk, we should expect to earn an additional margin of return to compensate for this.

Thus, the interest rate received from owning high quality bonds (loans) today is around 2% pa in the US and Australia. While that provides a 2% margin over the risk-free rate of return, it is a figure that has fallen considerably from the c.3.5% for making the same loan five years ago, or the 5% earned 10 years ago.

Further along the risk curve are high-yield bonds, essentially loans that are made to companies where there is a reasonable chance the borrower may default. This risk of borrower default is why high-yield bonds are also sometimes referred to as ‘junk bonds’. Today, the yield on these loans is 3.75%. This offers an additional return margin of 1.75% over high-quality bonds, but, again, is still considerably lower than the 5% interest rate on these loans five years ago or the 8% on offer 10 years ago.

High-yield bonds are not really high yield

The investment proposition with high-yield loans today provides a helpful framework to think about investing even further out along the risk curve, notably into asset classes like the sharemarket.

Earning an interest rate of 3.75% from lending to risky borrowers can hardly be thought of as a ‘high-yield’ proposition. Yet, while the interest rate has plummeted, the risks from holding these loans are largely unchanged. ‘Junk’ remains apt. We are bearing a high level of investment risk while expecting a low investment return.

If the academic textbooks are right, this same framework should apply to the highest risk asset classes, like the sharemarket, which also have been the places that investors have received the strongest gains in recent years.

Over the long run, global sharemarkets have generated annualised returns of 7.6% a year (MSCI All Country World net return index in $US terms, 31 December 1987 to 30 June 2021). However, over the past five years, this figure has been 14.5%. We would argue the disconnect between these two numbers has led to the steadily increasing future return expectations we see in many investors today, as illustrated in the Schroders study.

Unfortunately, forecasting longer-term sharemarket returns is not just a case of dragging our expectations back down to previous long-term averages. Market valuations are so much richer today than they have been historically, an attempt to forecast future returns based on fundamentals suggests we are in store for a period of returns that are much lower than this. And we are still left bearing the high risks that come with investing in this asset class.

The long and short of it

Looking out over the long run (typically five to 10 years) allows reasonable assumptions about things like asset class valuations, or sustainable rates of earnings growth, to play out.

As an institutional investor we are privy to many of these forecasts, and it is common for us today to see low-single digit return assumptions attached to sharemarket expectations. GMO is one high-profile forecaster that generously publishes all of its forecasts for everybody to see (and hold them to).

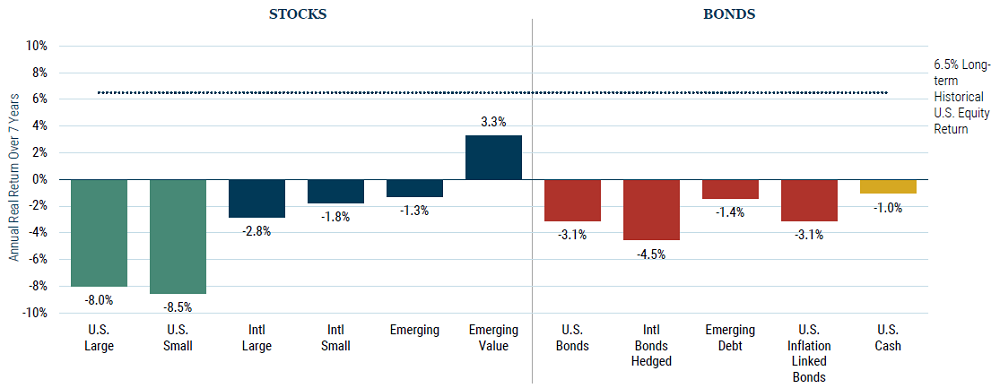

Using a set of assumptions that would be common for most professional investors, they project annualised global equity market returns of minus 2.8% over the next seven years.

GMO 7-year Asset Class Real Return Forecasts - June 2021

Source: GMO 7-Year Asset Class Forecast, 20 July 2021

Professional forecasters, of course, have an embarrassing proclivity for getting things wrong. However, the colossal gap between fundamentally-based forecasts and investors’ current expectations is worthy of reflection. Particularly since the basis for many investors’ current high expectations is simply that recent returns have been unusually strong.

The common disclaimer that ‘past performance is not indicative of future results’ may never have been more apt.

Miles Staude of Staude Capital Limited in London is the Portfolio Manager at the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.