APRA released a paper last week which gave some clarity to the question of just how well capitalised the Australian major banks are (but no clarity on where they need to get to). Despite the major banks claiming for the past five years that they are the best capitalised banks in the world, it seems they are not even in the top quartile. There is no agreement as to how much extra capital needs to be raised, but in one sense it doesn’t matter. Earnings Per Share and Returns on Equity may well be unchanged as banks will continue to practice regulatory arbitrage and the oligopoly will allow them to increase fees without much fuss. Still, it will be unarguably a better outcome for hybrid and debt holders.

Recap on what the fuss was all about

There’s been an ongoing discussion about how much capital banks should have. Although the Basel regulations are meant to standardise capital, each national regulator does its own renovations, so it’s not easy to compare capital levels between banks of different domiciles. The most important capital level is common equity (or CET1) and the minimum level for the four major Australian banks is 7% of risk weighted assets. Differences between regulators are myriad. For example, in contrast to other regulators, APRA says that banks need to put aside risk for any interest rate bets they take on their deposit book and APRA won’t allow banks to claim past tax losses as an asset (because this reduces the amount of tax paid in the future). This means that Australian bank capital levels would be naturally lower than their overseas counterparts. On the other hand, Australian banks set aside far less capital for housing risk than overseas banks which has the opposite effect of overstating domestic bank capital levels.

In a Media Release announcing the changes to residential mortgage risk weighting, APRA said, "This change will mean that, for ADIs accredited to use the IRB approach, the average risk weight on Australian residential mortgage exposures will increase from approximately 16 per cent to at least 25 per cent." IRB is 'Internal Ratings-Based', which allowed the major banks to use their internal models and assign low risk weights.

APRA’s report used some confidential data available to the Basel Committee. APRA came to the conclusion as at June 2014, that Australian bank equity capital levels were around the middle of the second quartile and 0.7% lower than the global first quartile level. So, for example, if the Australian banks capital levels (under APRA rules) are 8%, the top quartile of the world would be 8.7% (under APRA rules) or if Australian banks were judged on the Basel survey and the top quartile of banks had 11% CET1 levels, Australian banks would have 10.3% CET1 levels.

Second quartile is news for Australian bank CFOs

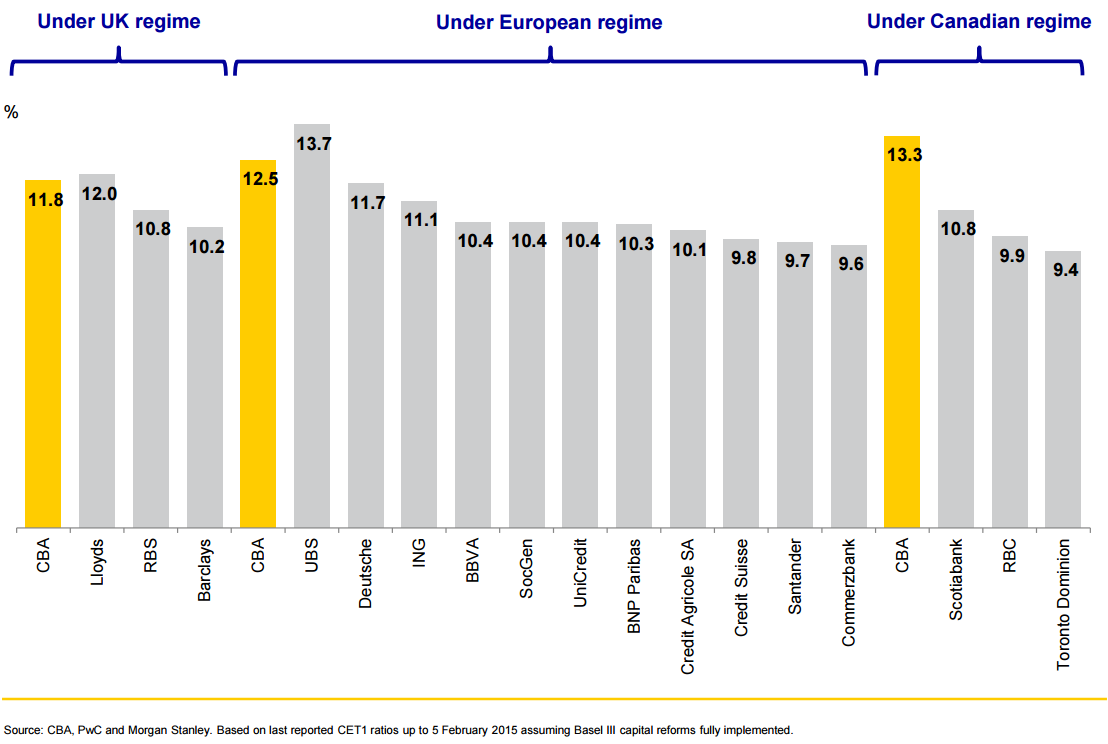

One of the most enduring attempts at agenda-setting by the banks is claiming they have the best capital levels in the world. Figure 1 below from the CBA February 2015 results is typical and gives the impression that on a comparative basis, CBA has a gold-plated capital structure. It purports to show what CBA’s CET1 capital levels would be under the various regulatory regimes operative in the UK, Europe and Canada.

Figure 1: CBA capital levels compared with banks in other countries, according to CBA

Unfortunately, the APRA paper calculated that the banks were middle second quartile. It’s hard to understand how the Australian banks can justify their claims on capitalisation and relative safety. APRA baulked a little as to whether the middle top quartile is an appropriate target, probably because global banks continue to grow capital and there are a number of large global banks who have to hold additional capital because they are Globally Systemically Important Banks or GSIBs.

How much additional capital is required?

No one actually knows how much extra capital is required, as it’s a combination of factors:

- An expectation that Basel 3 will soon be replaced by Basel 4

- Global banks continue to increase their capital levels

- Small changes in assumptions or bank structures can change nominal capital levels and regulatory capital adequacy materially

- APRA continuing its Delphic-ness by not telling anyone what might be an appropriate CET1 capital level. Even the analysts are confused. From a survey of five of the major analysts there was a range of $8 billion to $20 billion additional capital needed

- The extra capital needed to support the rise in risk weights on residential mortgages.

A few months ago we estimated that the banks needed to raise $20 billion if their mortgage risks were raised to international standards. They have since raised $8 billion, so our simple estimate is now $12 billion to $14 billion.

What do the banks do and does it matter?

There is no problem with the banks meeting whatever new targets APRA decides on. There is still a lot of cash floating around in Australia and the only issue is at what price the new equity is raised. Banks have been optimising their regulatory capital since 1994 when Westpac started buying back shares (between 1994 and 2004, the total number of shares decreased by 2%, but assets increased 161% and EPS 260%: that’s gold medal-winning regulatory arbitrage). They’ll do it again and may sell divisions or assets that don’t cut it in the new regulatory environment if it will produce a better EPS outcome. It’s an extremely effective oligopoly and if they have to issue more shares, which are potentially dilutive to RoE, EPS or DPS, they just put up interest rates and fees.

Although it’s not reflected in market prices, hybrids are now approximately $20 billion to $30 billion safer than they were three months ago. There might be a bit more supply over the next few years as banks attempt to push up their total capital levels, but we think that will be price-driven and at the moment raising hybrid capital is historically very expensive.

On a tangent, we are continuing to develop the view that while capital levels are important in protecting hybrid holders up to a certain point, at some stage the profitability of the bank becomes more important. It explains why the US banking system was able to move from ‘insolvency in 2010’ to repurchasing stock in 2013. Australian banks are wonderfully profitable, so the profit-generating capability becomes more and more important. For example, in 2007 banking system profits were $20 billion while in 2015, it will be more like $34 billion. It’s pretty easy to recapitalise when you are making that much money each year.

Campbell Dawson is an Executive Director at Elstree Investment Management, a boutique fixed income fund manager. See www.eiml.com.au. This article is for general education purposes and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.