This is an edited transcript of Michael Howell’s podcast interview with Hidden Forces’ Demetri Kofinas.

Michael Howell is Managing Director of CrossBorder Capital, a London-based independent investment research company. He’s also the author of ‘Capital Wars’.

Demetri Kofinas: What are the risks that are introduced to the economy, to financial markets, with [US] yield curve suppression?

Michael Howell: If they're starting to fund a lot of government spending through short-term bills which is the reality of what's happening, and let's say that the money funds or the banks start to buy that debt, this is pure monetization.

And this goes back to something that Stan Druckenmiller said six months ago when he was being interviewed. There was a well-known interview on YouTube that he expressed these fears where he said, if you look at the numbers that are coming out of the Treasury in terms of the quarterly refinancing statement, those numbers were the numbers that you would have seen in Latin America not in the USA.

This is a warning sign, this is bad, and if the Treasury keeps funding at the short end, and they start issuing more debt to banks, so the banks are holding Treasuries, what you're getting is this pure monetization of the deficit.

Look at U.S. money supply data now. Money supply, broad money supply in America, is beginning to tick up. Everyone says, well, that's great news. Well, let's look beyond that headline figure and drill down into why it’s picking up. It's not picking up because banks are lending to the private sector. Their hands are tied many ways because of regulation. It's because they're effectively de facto lending to the public sector. They're starting to fund these big deficits, and this is bad news for the long-term health of the U.S. economy...

… What you're now hearing is debate going on between the lines which is basically saying why don't we allow the banks or encourage the banks to own more Treasuries? Well, lo and behold, guess what happened in World War II or in the British case in World War I? What you saw was the banks owned lots of Treasury Securities and that's war finance.

Kofinas: What are the consequences to the real economy of this kind of suppression continuing? In other words, having this kind of distortion and duration, because interest rates on government bonds have an important influence on interest rates across the economy.

Howell: Correct. And I think the danger is – I mean, we can go back in history and look at why there is the obsession among the economics profession for interest rates. And my view is that that's wrong. There's too much fixation on interest rates, so much so that the Federal Reserve gets in a lather about the dot plot and everyone in the market tends to focus an awful lot on the dot plot diagram, about what the FOMC are thinking rates are going to be…

… But look, over the last 18 months, what you've seen is liquidity expanding, the markets gone up through that period, policy rate expectations have flip flopped from one side to the other. That hasn't really affected the market. What's driven the market is the flow of liquidity.

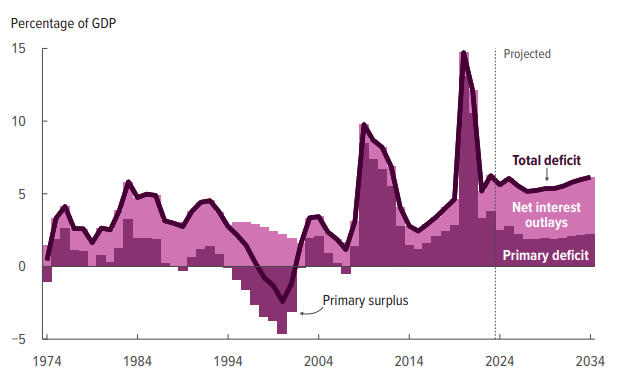

The reality is that what's happening in America is that fiscal policy is so loose, with a budget deficit running on close to 8% of GDP. It's a huge, huge fillip to the domestic economy. And that's what you're seeing.

US Budget surplus/deficit

Source: US Congressional Budget Office

Source: US Congressional Budget Office

Kofinas: How much is also that a lot of business, small businesses, consumers have long duration loans at lower interest rates, and they really haven't had the need to refinance? And is that a concern that if interest rates remain high long enough that eventually it's going to impact the economy because a lot of people are going to have to refinance at higher rates?

Howell: I've got sympathy with that view, Demetri. I think that that's quite feasible. The problem is, is that the longer you have interest rates at high levels, the more you hit the small to medium-sized business sector, and that matters a lot for U.S. productivity in the longer term.

But at some stage, we've got to address this point about debt, about trying to disincentivize debt. But I think the reality is what you can't see is interest rates coming down a lot from here. Certainly, that would be my view. I think they stay higher for much longer.

Kofinas: Where do we go from here in terms of financing the deficit?

Howell: There's an old saying in Ireland is that – for the lost travelers, if you want to get to Dublin, don't start from here. And that's the reality that most Western governments have got a face. Now, I'm not picking on the U.S. because the U.S. is the cleanest shirt in the laundry by far. A lot of other countries are in far worse shape.

The reason that the U.S. is maybe easy to pick on is that the U.S. is very transparent in terms of its future finances. The Congressional Budget Office does a brilliant job in actually projecting debt out to 2050 and in detail over the next 10 years. So, you pretty much know what's coming. You're looking at deficits, 8%, 9% of GDP going out into the foreseeable future. And that is something that if you look back, if you go back, as I say, 20 years ago, if you said that, people thought you're crazy to project those sorts of numbers. But that's the reality we face.

Kofinas: I think you fall within the camp of people who view QE as actually a policy that raises term premia counterintuitively for people, because most people think QE actually lowers rates. But the arguments of people like you fall in the camp of those who believe that QE actually raises interest rates because it creates a risk-on environment. But how does that square with the government monetizing its debt? I mean, doesn't the government just become the larger purchaser of government debt and yields are therefore kept low?

Howell: Yeah, but we sort of go back to an Alice in Wonderland world where Alice said to the Red Queen, you've got to run faster just to stand still. And I think that's the reality is that if the Fed starts to purchase Treasuries, by definition, if it's taking Treasury supply out of the system, it must by demanding Treasuries be pushing their prices up and capping their yields.

But at the same time, it's issuing liquidity into the system. And as more liquidity goes into the system, investors don't want to take risk, and they don't have any demand for safe assets. So, their demand for safe assets crumbles. And if you look at all these studies that are done by the Federal Reserve, by academic economists and whatever else, what they're looking at purely is the supply impact of central bank purchases of Treasuries on term premia. They're not looking at the second-round effects that come through as the private sector says, well, we've got no need for these safe assets now.

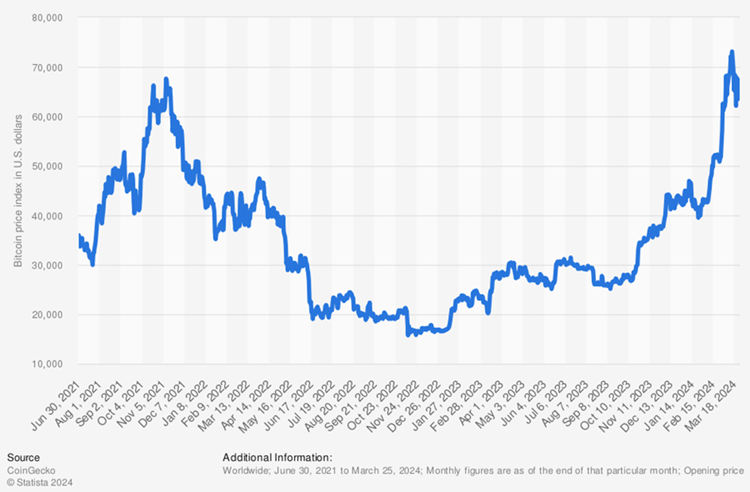

Kofinas: We'd rather have Bitcoin.

Howell: Exactly. Well, wouldn't you?

Kofinas: Yes, at the limit. The last thing I want to own is U.S. government debt. So, is this another way of saying that this is the Japanification of the U.S. bond market that we're seeing in the United States, what we saw roughly in Japan just in several decades earlier?

Howell: Yes. But there's a very important point that comes with that observation, which is the critical one. And this is what I guess Treasury officials or Fed officials have woken up to. Did it matter?

Kofinas: Did what matter?

Howell: Did the Japanification matter for Japan? You end up with the Bank of Japan owning most of the debt. Okay, fine. But what's the cost to Japanese economy? Now, I would argue the cost is that the Japanese economy is a slow growth economy that's going to be very difficult for it to pick up because you've got this huge burden of debt to fund, and the government is monetizing that. But in terms of the implications for there's been no recession, inflation hasn't picked up materially, interest rates remain pretty benign, the economy just rolls on. I mean, it's not a disastrous scenario. And this is the fact that if the U.S. starts to monetize debt, which we're arguing it is, you're not going to go to a hyperinflation state or deep recession. What you're going to do is the can is kicked down the road, you got a higher level of inflation. And ultimately, as my friend and your friend Russell Napier says, this is financial repression. So basically, people who are debt holders lose out over the over the longer term.

Kofinas: Well, in any case, I mean, that's sort of the intention there. But the demographics are very different in Japan. We have tons of immigration here. So, I wonder if we can actually accomplish that without much higher levels of inflation in the United States.

Howell: It's quite possible. I'm not in the camp that says that you get very high inflation. I think you'll get some seepage of this liquidity. It will spill over. Monetary inflation is a component of 'high street' inflation. It's not the only factor. 'High street' inflation is a hybrid cocktail of both monetary inflation, which is devaluing paper money and cost factors. So, if you get oil prices suddenly collapsing, or you get a big productivity shock, or the Chinese help us out by cutting their prices, then you're going to see cost deflation in the 'high street'. And that basically means high street inflation is not so badly affected. But equally, it can go the other way. So, what we're saying to our clients is, what you want in this environment are monetary inflation hedges. So, what you want are things like gold, which is a long-standing monetary inflation hedge or Bitcoin, which seems to be actually acting like exponential gold, it's sort of becoming a monetary inflation hedge par excellence.

Gold Spot Price USD/oz

Bitcoin (BTC) price per day from June 30, 2021 to March 25, 2024 (USD)

Kofinas: Is it just me, or is the Fed collaborating with the treasury more than it has at least in the last 40 years?

Howell: I would agree 100%. I think that's absolutely right. I mean, Janet [Yellen] is one of the most political Treasury Secretaries I can remember.

The Fed is a much more political institution than it has been certainly in my estimation. So, I think we're there. But I think the reality is – and I keep coming back to this – is where we are, is we're in a monetary inflation regime. That doesn't mean to say you're going to get hyperinflation in the high street. It does probably mean you get a higher level of inflation running on. So, it's not going to be 2%, 3% that we've been used to in the last decade. It's more likely to be in the sort of 5%, maybe 6%, but that's not hyperinflation. But it does mean that if you're a debt holder, your wealth gets progressively eroded.

Now, I think you've got to extrapolate that globally and then say, well, how does America hold up in that environment? Because America basically has to sell debt, but then so do many other countries. And if the dollar is the cleanest shirt in the laundry, as I've said, against other units like the euro or the yen or sterling, pound, then the U.S. is going to fare better than these other countries. And their ability to fund is going to be compromised.

This is an edited transcript of Michael Howell’s podcast interview with Hidden Forces’ Demetri Kofinas.