In the world of investments the start of a new year is a time of heightened activity, as performance data from the previous year becomes available. For example, balanced options (between 60% and 76% in growth assets) have, on average, generated an annualised return of 7.1% p.a., net of investment fees and tax, for the ten calendar years to 31 December 2013. This equates to a real (after-tax) return of 4.2% p.a. over the period. Given a typical real return objective of 3– 4% p.a. over rolling multi-year periods, this result for the ‘average’ balanced super option would seem highly satisfactory from a pure investment perspective.

An in-depth review, however, finds only one calendar year (8% in 2007) was close to the annualised average of 7.1%. More commonly, high return years (e.g., 16.3% in 2013) were balanced by low return years (e.g., -19.7% in 2008). How ‘average’, therefore, are long-term average returns? How closely do they match returns as experienced by individual members? More importantly, does it matter if they don’t?

Peeking under the hood of a retirement projection

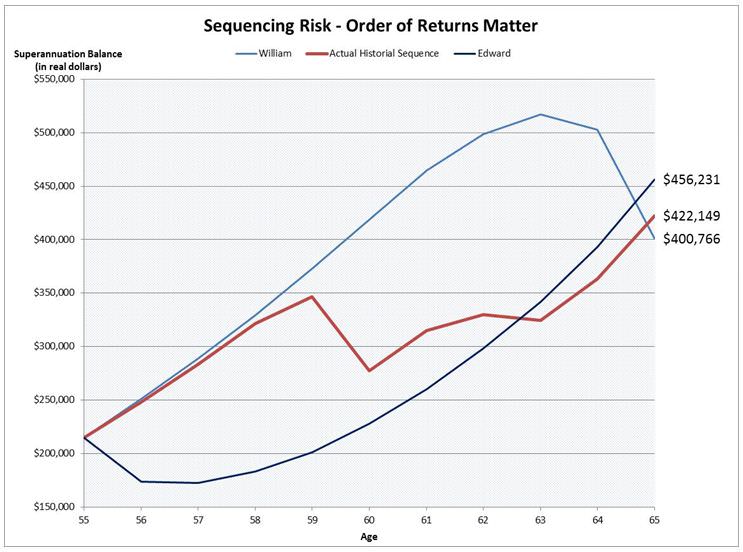

To answer these questions let’s look at a real-world scenario incorporating actual returns over the 2004 to 2013 period. We examine a hypothetical example of two super fund members, William and Edward. Both turned 55 on 1 January 2014 and both intend to retire in ten years at age 65. Their circumstances are identical: super balance of $215,000 on 1 January 2014, and income of $85,000 escalating at 4% p.a., on which employer super guarantee contributions (as currently legislated) are paid, with no further contributions. For ease of computation, non-investment related fees and insurance premiums are ignored in this example.

Seeking advice, both men discover that they should aim for a retirement super balance of $430,000 in real (2013) dollars. The advisor’s projections indicate that if their respective super options generate an annualised return of 7.1% p.a. and inflation matches the average for the last ten years, they should retire with super of $432,000 in real dollars.

Rather than the average 7.1% p.a. return, let’s model outcomes with year-to-year variability based on the historical sequence of calendar returns from 2004 to 2013. We’ll change only one factor: re-ordering this sequence such that Edward’s returns are ordered from worst to best over the period, whilst William’s are a mirror image, with his worst return in year ten.

The results for this modelling exercise are depicted below:

The red path shows how Edward and William’s super would have grown if the returns from 2014 to 2023 matched exactly those from 2004 to 2013 in size and chronological order. However, once we change the return sequence as described above, both end up with retirement balances significantly different to the projection of $432,000, and some $55,500 different from each other. Why?

The answer is sequencing risk – the risk to an individual’s wealth of receiving the worst returns in their worst order. Both Edward and William experience a -19.7% return once in their final ten years before retirement. It is William who is affected to a far larger degree. He experiences his worst return (-19.7%) at the point of maximum portfolio size, decimating his year 10 starting balance of $503,000. Edward’s -19.7% return year occurs off a starting balance of $215,000.

William’s worst return year also coincides with his largest cash flow into superannuation, with some $12,800 of net nominal contributions made in his tenth year, compared to some $7,000 in Edward’s first year. These aspects of sequencing risk have come to be known as the ‘portfolio size effect’ [Basu and Drew, 2009]: sequencing risk increases with the magnitude of dollars at risk, reaching its zenith at or near the end of an investment time horizon.

The above example demonstrates that returns as experienced by individuals are cash flow sensitive and path dependent. Both the timing of cash flows and the order of returns matter in producing the final dollar outcome (terminal wealth) from which a retirement lifestyle is funded.

Investment risk and sequencing risk are related, but not the same thing. It is simultaneously possible for an individual to achieve an investment return objective over an entire investment horizon (as with the 7.1% p.a. ten year annualised return) and not meet a terminal wealth objective (the unfortunate William) due to the order of returns on their particular path to retirement.

Ramifications for superannuation

Sequencing risk creates a particularly troublesome dilemma in retirement planning. At its core, sequencing risk is a function of portfolio volatility: reduce it and you mitigate the sequencing risk effect. Do this by down-weighting growth assets and you might not have the growth engine you need to combat inflation and longevity risk through a retirement of uncertain length. Getting the balance right is a very delicate dance, and a challenge for the entire superannuation sector.

Many MySuper funds have implemented lifecycle strategies that periodically de-risk members once in the retirement risk zone. These developments are in their infancy, with their effectiveness hobbled by operational complexity and regulatory constraints. They are a mass-personalised solution, segmenting members into groups that de-risk together along a pre-determined ‘glidepath’, not an individualised response to sequencing risk. Enhancements continue to be made in this area.

Financial planners can help individuals negotiate their personal retirement risk zone, focussing clients on achieving wealth objectives and income goals, incorporating superannuation into the totality of financial resources available for retirement.

Sequencing risk will be a sizeable challenge for SMSFs, which tend to have a significant weighting to Australian shares that pay tax-advantaged franked dividends. Whilst this might boost after-tax returns in the accumulation phase, portfolio volatility may be dominated by equities. A tendency to defer the sale of assets with unrealised capital gains tax liabilities until in pension mode further exacerbates the problem. In short, SMSF trustees might inadvertently be allowing the tax tail to wag the sequencing risk dog.

Harry Chemay is a Certified Investment Management Analyst and a consultant across both retail and institutional superannuation. He has previously practised as a specialist SMSF advisor, and as an investment consultant to APRA-regulated superannuation funds. The example used in this article appears for illustrative purposes only, and is not intended to be taken as personal or general financial advice.