Australians’ superannuation account balances ebb and flow with investment returns delivered by markets. If you had to choose between a few years of negative investment returns at the start of your retirement or the end of your retirement, which would you pick? Is it better to get the run of ‘bad luck’ out of the way in the beginning? Spoiler alert: a string of negative returns early on in retirement can significantly impact how long your money will last. Let’s take a look.

Why the order of investment returns can make a difference

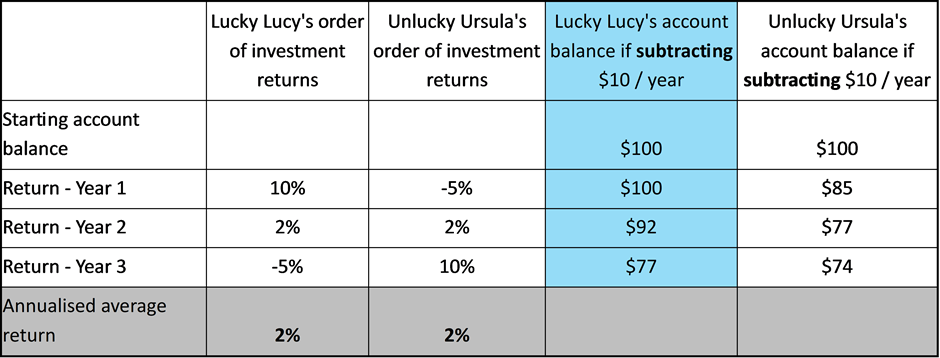

Long-term, average investment returns dominate the superannuation headlines. But, average investment returns don’t factor in cash flows. Once cash flows are introduced, the order of investment returns can make a difference. Let’s look at a simplified example in Exhibit 1. It compares two retirees over a three-year period, both withdrawing $10 per year. The annual returns delivered are +10%, +2% and -5% for Lucky Lucy and -5%, +2% and +10% for Unlucky Ursula. So, while their annualised average returns are the same (2% p.a.), for the purposes of this example, the order of the annual returns is different.

Exhibit 1: A different order of annual returns and the impact if subtracting money from an account

Lucy’s order of annual returns proves more favourable for someone withdrawing cash ($10/year) – her account balance ends up $3 better off than Ursula’s balance. This is because the positive returns at the start are offsetting the fixed dollar withdrawal amounts. On the other hand, Ursula’s account balance is depleted by both the fixed dollar withdrawal amount and the negative return. This is the simple logic of sequencing risk: when you start spending your super and your account balance reduces, it is harder to benefit from market recoveries.

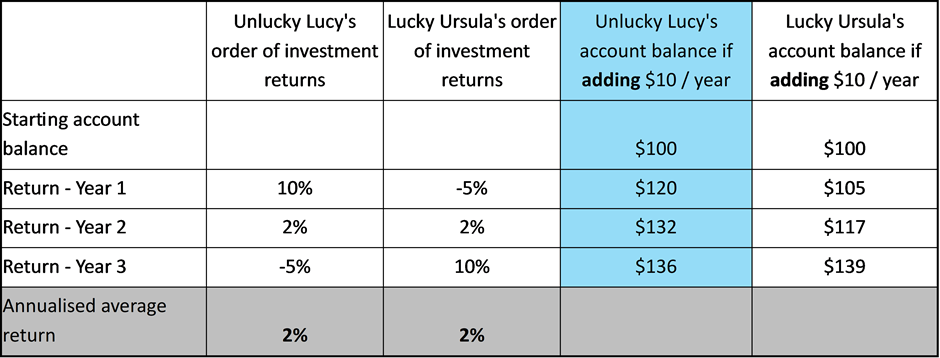

Of course, this works in reverse when you’re saving for retirement. Lucy ends up unlucky. She is $3 worse off than Ursula when they each add $10 per year to their account and when Lucy receives the same order of annual returns as she did in Exhibit 1. And to be clear - if there were no contributions or withdrawals into or out of the account, their outcomes would be identical.

Exhibit 2: A different order of annual returns and the impact if adding money to an account

This effect is amplified around retirement age when your account balance is most likely to be substantial. Investment returns have an outsized impact (in dollar terms) on larger balances than smaller balances. For example, a +15% annual return is more valuable when your balance is $400,000 than when it is $40,000. So, earning a string of positive or negative returns during this period can make a big difference to how long your money will last.

Sequencing risk illustrated

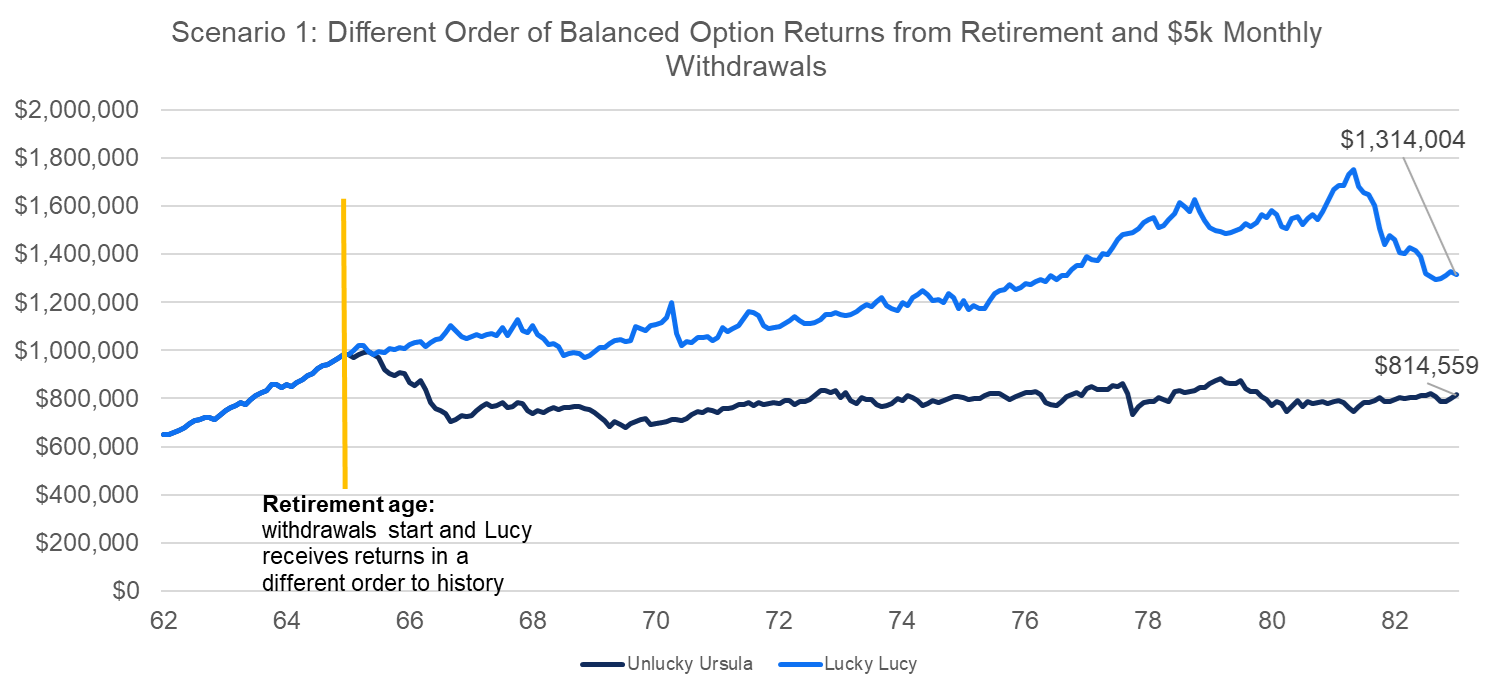

Let’s now look at a more realistic example. Imagine it’s back in mid-2007 and Ursula and Lucy have just retired with identical circumstances. They are both: 65 years old; invested in their fund’s balanced option (for the purposes of this example, the UniSuper Balanced Option has been used) and withdraw $5,000 on the last day of each month from their super account.

Let’s make one key adjustment for them – the order of their investment returns between 2007 to 2025. Let’s give Ursula the order of the Balanced Option’s investment returns which actually unfolded between 2007 and 2025. Remember 2007 marked the start of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) – and so Ursula receives a string of negative returns early on in her retirement. Let’s give Lucy the same investment returns between 2007 and 2025 but in reverse order. Instead of earning the returns of the GFC early in her retirement, she earns the positive investment returns delivered in 2025 early in her retirement. Late in retirement, she incurs the GFC’s string of negative returns. Scenario 1 shows the different outcomes, purely from a different sequence of monthly returns. On 30 June 2025, Ursula’s balance is just over $800,000, whilst Lucy’s exceeds $1.3 million.

In isolation, both have done quite nicely. After all, the objective of super is not to pass away with the highest balance, but the $500,000 difference is stark. It’s attributable to the different order of returns in retirement, once even modest withdrawals start.

*For the purposes of this comparison, we have referenced the actual monthly accumulation returns of UniSuper’s Balanced Option for the period 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2025. Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. Option returns are calculated after investment expenses and taxes, but before account-based fees are deducted.

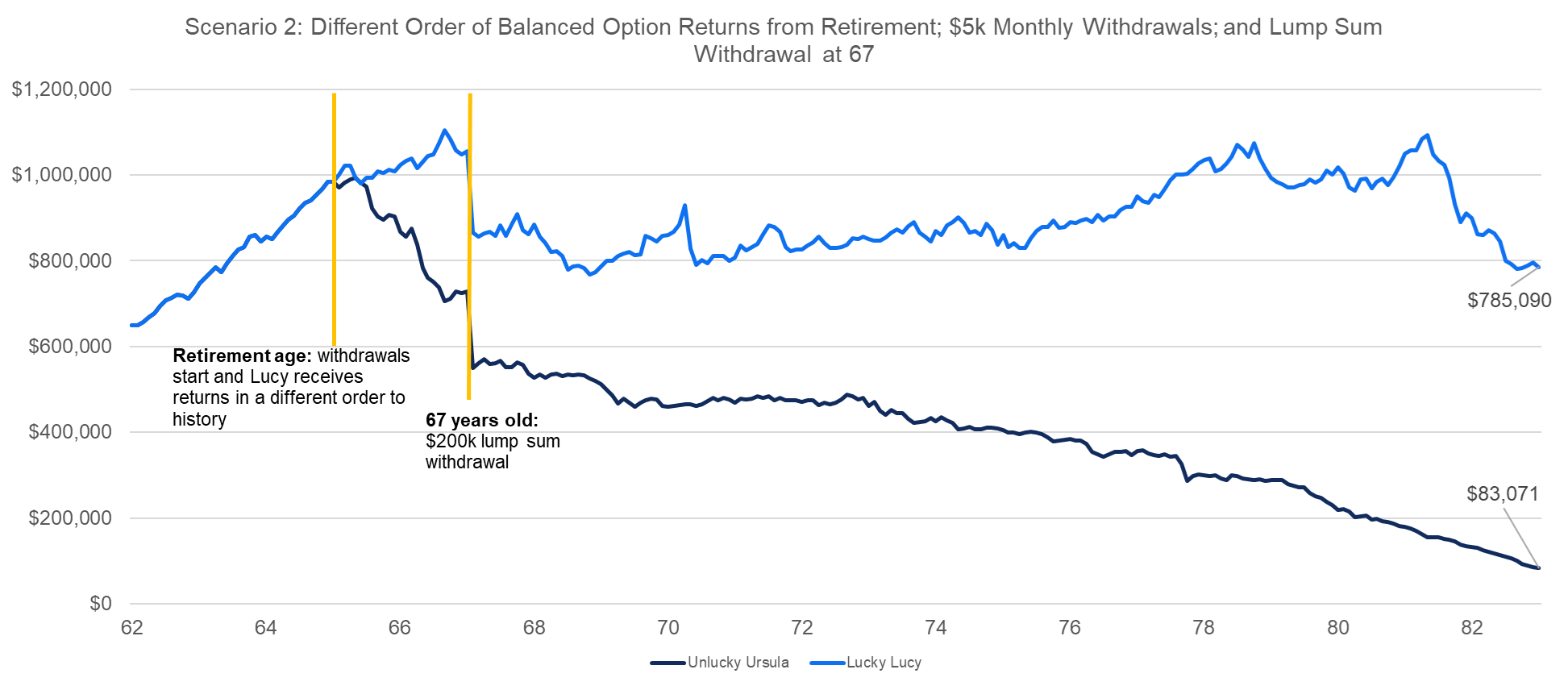

Does the size of withdrawals make a difference?

Modest monthly withdrawals are one thing - large one-off withdrawals are another. These really exacerbate sequencing risk. This is illustrated in Scenario 2 (applying the same sequencing of annual returns as Scenario 1) when Ursula and Lucy decide to pay down their mortgages two years into retirement (in mid-2009). They both withdraw a lump sum of $200,000 at the same time.

Many retirees fear running out of money and an unlucky order of returns will impact your final balance. You can see Ursula is treading that line, with her balance unlikely to last two more years.

For the purposes of this comparison, we have referenced the actual monthly accumulation returns of UniSuper’s Balanced Option for the period 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2025. Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. Option returns are calculated after investment expenses and taxes, but before account-based fees are deducted.

Get lucky early in retirement or be prepared to manage sequencing risk

The scenarios presented are simplified and the data cherry picked for effect. But sequencing risk is real and large purchases exacerbate it.

In recent years, market sell-offs (e.g. COVID-19 and Liberation Day in 2025) have been short and sharp. The prolonged and severe nature of the GFC exacerbated sequencing risk. While we hope it won’t be an issue for most Australians, it’s important to be aware of how a string of negative returns can impact your retirement.

There are ways to manage this risk and some of the behavioural biases that accompany it, but all involve accepting certain trade-offs [see my next article on managing sequencing risk]. You can’t control the sequence of returns, but plan ahead and seek advice to help make your money last in retirement.

Annika Bradley is Head of Advice Strategy, Research & Technical at UniSuper, a sponsor of Firstlinks. She brings over 20 years of experience across investments and wealth management in both the public and private sectors. In previous roles Annika worked with Morningstar and QSuper. The information in this article is of a general nature and may include general advice. It doesn’t take into account your personal financial situation, needs or objectives. Before making any investment decision, you should consider your circumstances, the PDS and TMD relevant to you, and whether to consult a qualified financial adviser. Issued by UniSuper Limited ABN 54 006 027 121 the trustee of the fund UniSuper ABN 91 385 943 850.

For more articles and papers from UniSuper, click here.