Many of you will have read my article “Can the sequence of investment returns ruin retirement?”. It introduced 'sequencing risk' and how a string of negative returns can impact your retirement. Here, we focus on how it can be managed.

In fact, the best antidote to sequencing risk is luck. If history is a guide, most Australians hopefully won’t encounter a prolonged string of negative returns early in retirement. But hope is not a strategy.

Managing sequencing risk involves trade-offs and we look at two levers available: your withdrawal strategy and your investment strategy. Finally, we consider the role that a bucketing strategy might play.

Can a flexible withdrawal strategy manage sequencing risk?

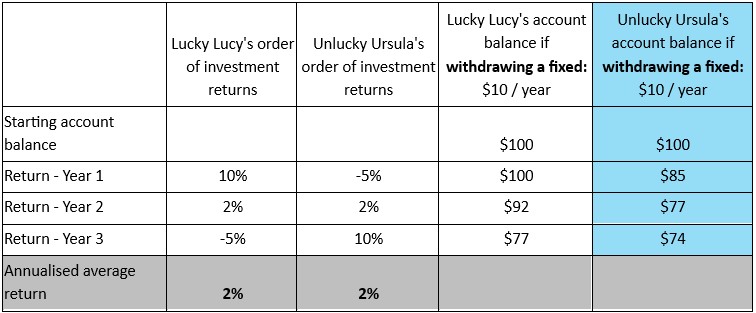

My earlier article showed the impact arising from the interaction between fixed cash flows out of a portfolio and the order of investment returns (Exhibit 1). In this case, Ursula received the unlucky order of investment returns.

Exhibit 1: A different order of annual returns and the impact if withdrawing a fixed amount from an account

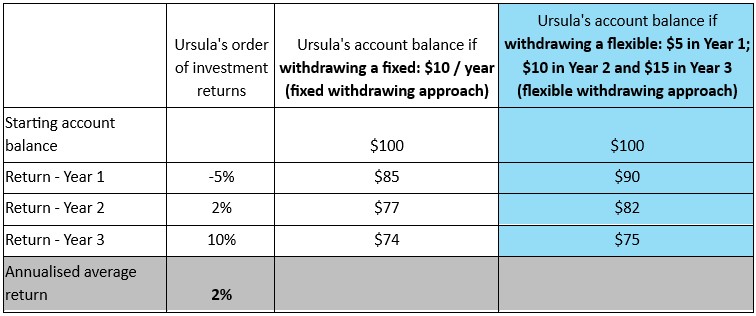

But what if Ursula decides to change her spending behaviour? What if she withdraws varying amounts (versus a fixed amount) each year from her account, in response to market conditions? Let’s call this a “flexible” withdrawal strategy. For example, in Year 1 when the market drops, she takes $5 instead of a fixed $10. But in Year 3, when markets accelerate, she takes $15. Exhibit 2 shows her end balance is healthier when withdrawing flexible annual amounts – even though the amount withdrawn in total over the 3-year period is the same as that shown in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 2: A flexible withdrawal strategy depending on market conditions

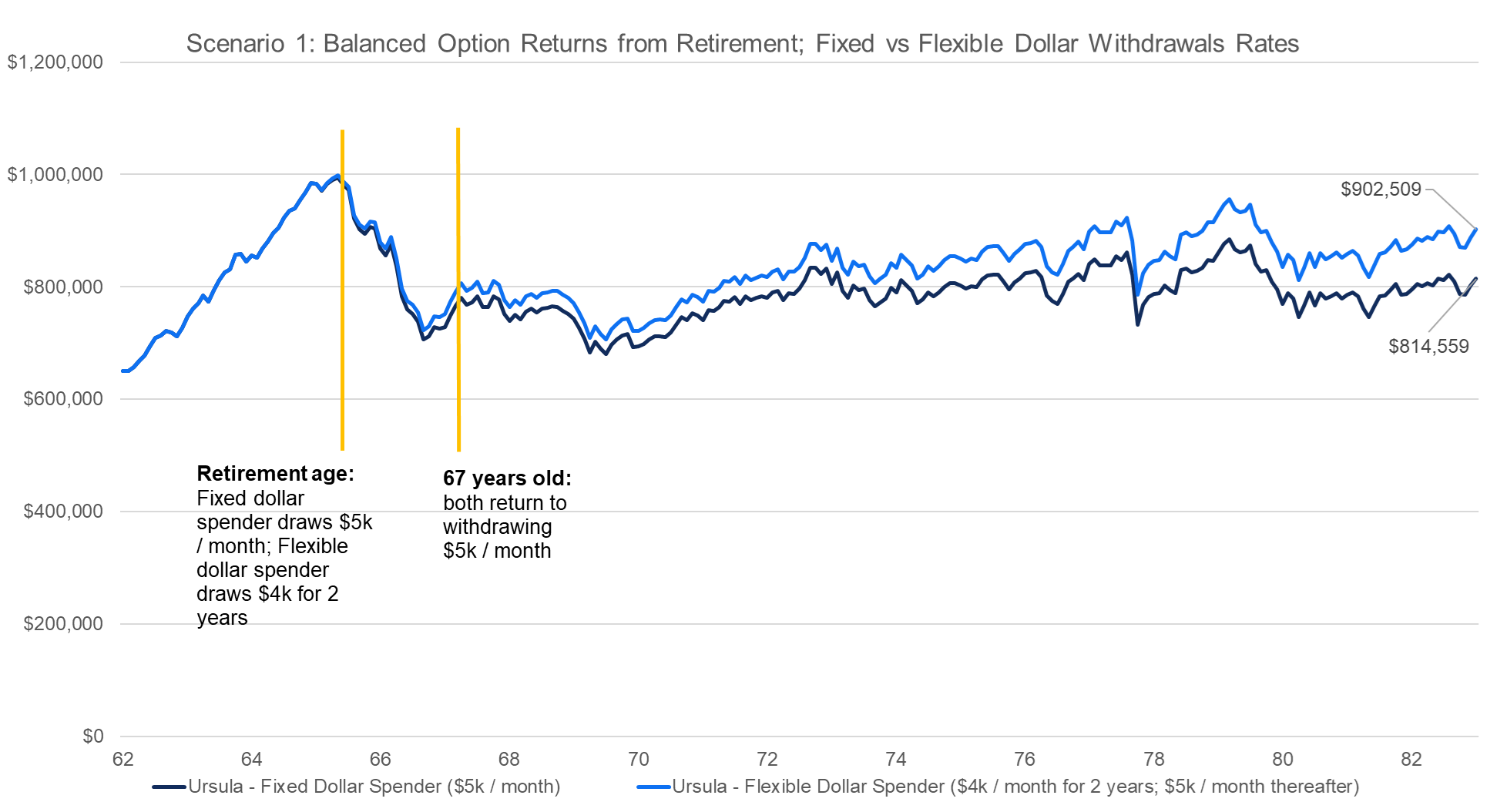

Let’s revisit the more realistic example from the earlier article. Recall that it’s mid-2007 when Ursula retires and due to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) she receives a prolonged string of negative returns early on in retirement. But, by adopting a flexible approach (light blue line) and withdrawing $4,000 per month for the first two years of retirement (when markets are dropping) instead of $5,000 per month (dark blue line), her final balance is almost $90,000 higher at the end of the period.

For the purposes of this comparison, we have referenced the actual monthly accumulation returns of UniSuper’s Balanced Options for the period 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2025. Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. Option returns are calculated after investment expenses and taxes, but before account-based fees are deducted.

Percentage-based withdrawal amounts

Remember, the government’s mandated minimum withdrawal rates for superannuation are percentage based (as opposed to a fixed dollar amount). This acts as a ‘built-in’ flexible withdrawal strategy.

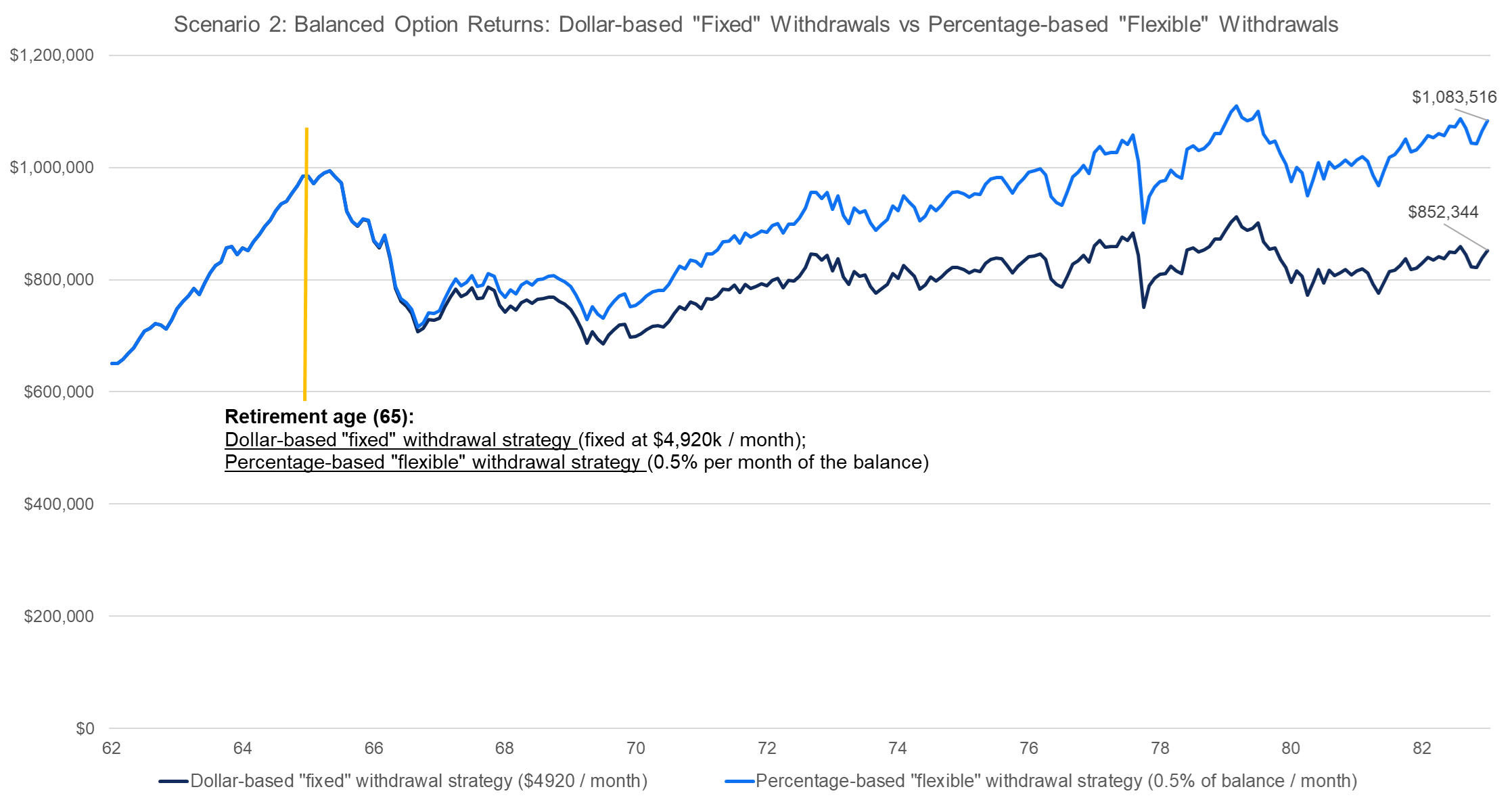

Scenario 2 compares a percentage-based 'flexible' strategy to a dollar-based 'fixed' strategy.

Let’s assume Ursula retires at age 65. Under the percentage-based strategy she withdraws 0.5% per month of her starting balance in retirement (roughly $984,000) which equates to $4,920 in the first month. Under the flexible strategy, the withdrawal amount changes for each subsequent month as a result of the change in the outstanding superannuation balance – ranging from $3,500 to $5,500. The total income withdrawn is just over $1 million using a ‘flexible’ strategy. Contrast this with the dollar-based withdrawal strategy which is fixed at $4,920 each month. The total income drawn under the ‘fixed’ strategy is about $66,000 higher, but you can see from the below graph that the end balance is $230,000 lower.

Of course, the story depends on the investment returns. If you encounter a string of positive returns early in retirement and employ a flexible spending strategy – you may spend more in total. The scenarios are endless.

For the purposes of this comparison, we have referenced the actual monthly accumulation returns of UniSuper’s Balanced Options for the period 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2025. Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. Option returns are calculated after investment expenses and taxes, but before account-based fees are deducted.

However, under this specific scenario, it’s clear that a flexible withdrawal strategy helped manage sequencing risk. But are you prepared to accept this trade-off?

We’ve all tightened our belts at times – due to changes in job or salary or the need to meet different expenses (for example, private schooling). But flexible spending won’t suit everyone in retirement. Particularly, in the early, active years when you might like to travel and spend more. It’s a trade-off – how important is a steady dollar amount each month versus the possibility of a higher balance at the end?

Does the investment option you pick help manage sequencing risk?

The investment option or mix of options you choose play a role, but there are also trade-offs here. Taking less investment risk typically narrows your range of outcomes when it comes to sequencing risk, but also typically results in a lower balance in the long run.

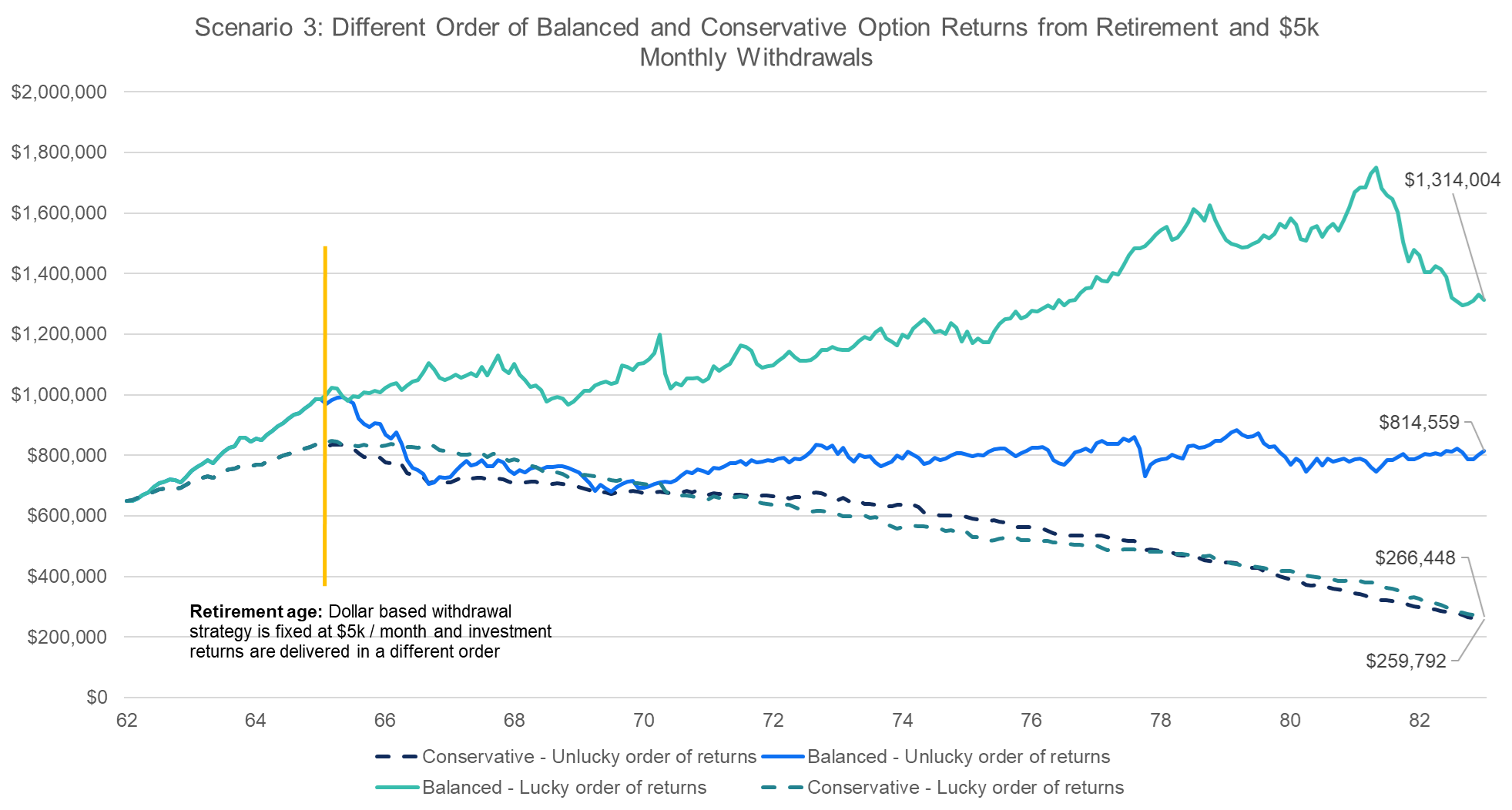

Scenario 3 draws on the ‘lucky’ and ‘unlucky’ return series from the previous article, while withdrawing a fixed $5,000 per month. To recap, in our previous article we looked at two series of investment returns ordered differently upon retirement. The ‘unlucky’ order of returns (based on the actual returns of UniSuper’s Balanced Option between 30 June 2007 and 30 June 2025) when the GFC came early in retirement. And the ‘lucky’ order of returns – simply the reverse order of the ‘unlucky’ returns and the GFC comes very late in retirement. In this scenario, the different final balances are solely attributable to a different order of investment returns once even modest withdrawals start (refer solid green and blue lines in the graph below).

But, what happens if we use a ‘lower risk’ investment? Let’s use UniSuper’s Conservative Option’s investment returns instead of the Balanced Option over the same period and apply the same methodology as above (refer dashed green and blue lines below). The end balances of the Conservative ‘lucky’ and ‘unlucky’ order of returns are within $7,000 of each other (compared to $500,000 for the Balanced Option). The ‘range’ of potential outcomes has narrowed dramatically.

Now note the end balances. The growth potential available from a Conservative Option is typically lower than a Balanced Option and this result is a classic example. Even the Conservative Option’s ‘lucky’ order of returns ends up more than $500,000 different to the Balanced Option’s ‘unlucky’ order of returns. While cherry picked for effect, the lesson from this example shines through when modelled over many scenarios and timeframes.

An investment option with lower growth prospects is generally less prone to the impact of a lucky or unlucky order of investment returns. That is, the range of outcomes is generally narrower, but the trade-off is typically a lower long-term balance. It’s worth considering what is more important to you? For some people a large bequest for family members is important, for others it’s prioritising return stability.

For the purposes of this comparison, we have referenced the actual monthly accumulation returns of UniSuper’s Balanced and Conservative Options for the period 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2025. Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. Option returns are calculated after investment expenses and taxes, but before account-based fees are deducted.

Does ‘bucketing’ help manage sequencing risk?

Finally, let’s look at the role a bucketing strategy might play in managing sequencing risk. ‘Bucketing’ is when the anticipated amount of money for either a large purchase or a few years of future spending needs is placed in a separate lower risk bucket. The two main impacts of this strategy are:

- Growth asset reduction: establishing a lower risk bucket reduces the portfolio’s overall exposure to growth assets (and generally results in a narrower range of outcomes as we saw above); and

- Mental accounting: putting money aside into a lower risk bucket can help manage loss aversion, as a person may be less likely to respond emotionally to falls in the value of the higher risk bucket if they know their immediate spending needs are met by the lower risk bucket.

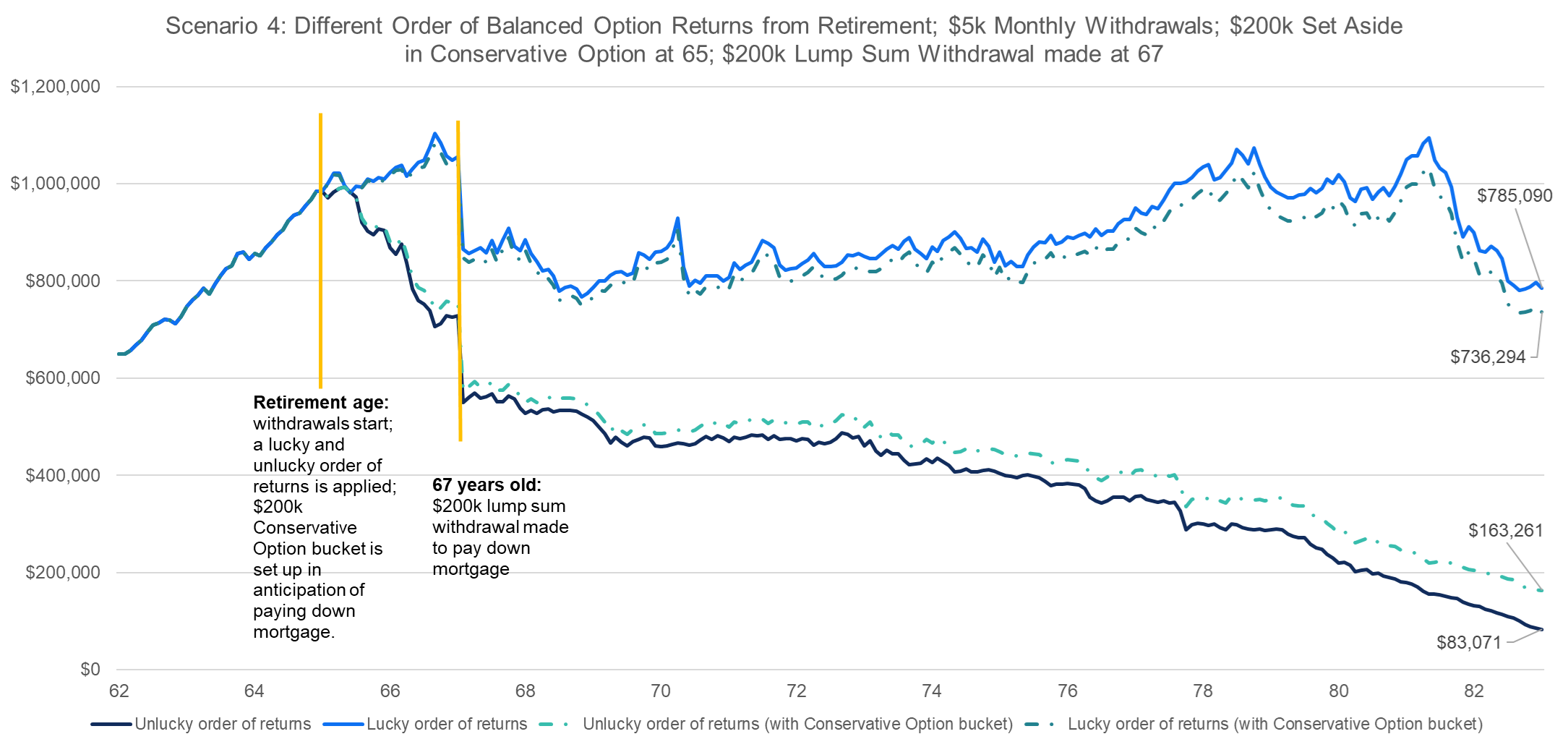

Scenario 4 shows the outcome of establishing a $200,000 ‘Conservative Option bucket’ on 30 June 2007 in anticipation of paying down a mortgage two years later. The allocation to the ‘Conservative Option bucket’ for this two-year period results in lower overall portfolio exposure to growth assets. If the ‘lucky order of returns’ is received (top two lines), the ‘bucket’ strategy (i.e. lower overall allocation to growth assets depicted by the dashed line) means a lower balance at the end. But if the ‘unlucky order of returns’ is incurred (bottom two lines), a ‘bucket’ strategy is beneficial. The end balance is around $80,000 healthier. More trade-offs…are they worth it?

For the purposes of this comparison, we have referenced the actual monthly accumulation returns of UniSuper’s Balanced Option for the period 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2025 and UniSuper’s Conservative Option for the period 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2009 (the two years in which the “bucket” strategy is applied). Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. Option returns are calculated after investment expenses and taxes, but before account-based fees are deducted.

Bucketing helps manage loss aversion

Managing loss aversion is the real magic of a bucket strategy. If a Conservative Option ‘bucket’ gives you comfort that your short-term future cash needs are met and as a result, you are less likely to adjust your overall investment strategy in response to market falls, it may be worth the potential trade-off.

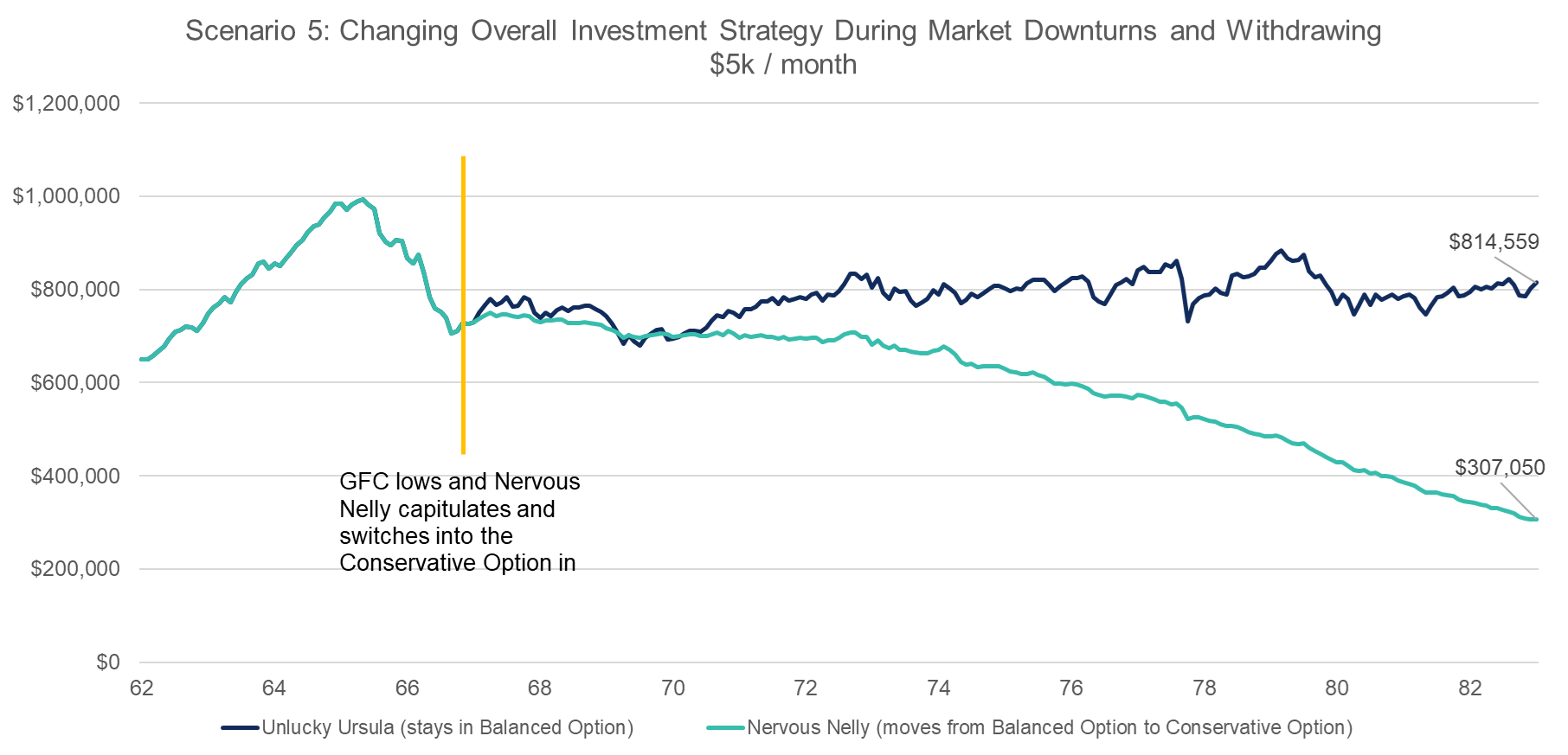

Let’s look at Scenario 5. It shows materially different outcomes. Ursula rides out the prolonged string of negative returns, whereas Nelly can’t and switches into a ‘safer’ Conservative Option at the lows of the GFC. This means Nervous Nelly’s portfolio doesn’t recover as strongly.

For the purposes of this comparison, we have referenced the actual monthly accumulation returns of UniSuper’s Balanced Option for the period 1 July 2004 to 30 June 2025 and UniSuper’s Conservative Option for the period 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2025. Please note that past performance isn’t an indicator of future performance. Option returns are calculated after investment expenses and taxes, but before account-based fees are deducted.

So, yes, bucketing can play a role in managing sequencing risk. It reduces the overall growth allocation, which generally means a narrower range of outcomes, but a lower potential balance at the end. However, introducing a mental accounting framework can help manage loss aversion and potentially helps you to stay the course if you’re unlucky enough to encounter a prolonged string of negative returns early on in retirement.

Sequencing risk can be managed

Retirement may last for many years, so it’s important to select the right investment strategy for your time-horizon and investment tolerance and ride out market ups and downs. When it comes to sequencing risk, it’s better to get lucky. There are no silver bullets, but if encountered early in retirement, consider the trade-offs best suited to you.

Some people want more certainty about withdrawal amounts and account balances, others are willing to accept more ups and downs in exchange for a potentially higher balance at the end. Both are valid perspectives; it depends on your preferences. And while a bucketing strategy does simply reduce your overall growth allocation, it can be a good approach, particularly if you are a Nervous Nelly. You can’t control the sequence of returns, but you can plan ahead and seek advice.

Annika Bradley is Head of Advice Strategy, Research & Technical at UniSuper, a sponsor of Firstlinks. She brings over 20 years of experience across investments and wealth management in both the public and private sectors. In previous roles Annika worked with Morningstar and QSuper. The information in this article is of a general nature and may include general advice. It doesn’t take into account your personal financial situation, needs or objectives. Before making any investment decision, you should consider your circumstances, the PDS and TMD relevant to you, and whether to consult a qualified financial adviser. Issued by UniSuper Limited ABN 54 006 027 121 the trustee of the fund UniSuper ABN 91 385 943 850.

For more articles and papers from UniSuper, click here.