Last week in Firstlinks, Dr Shane Oliver enlightened us on how the anticipated increase of $500 billion in public debt due to the COVID-19 crisis will be paid for. The $200 billion in spending contained in the three stimulus packages offered by the Morrison Government plus the hit to the public revenue of $300 billion through reduced taxes from the economic downturn will be funded via the issuance of government bonds and additional borrowings.

However, in his concluding comments, Oliver briefly mentioned that long-term consequences may include forgoing the next round of personal income tax cuts due in 2022 and the imposition of a deficit levy. These options and others are explored in this article.

Notwithstanding the terrible human cost of the pandemic and the impact on many people’s livelihoods, we should be prepared for more financial pain once we get through the immediate threats posed by the pandemic. While this week, Scott Morrison reaffirmed that once the crisis is over, the Coalition Government will be returning to ‘conservative economic policies’, the sheer magnitude of the generous responses coupled with the economic downturn will leave a significant financial bill to pay.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has indicated the debt will be repaid over the long term. We must brace ourselves for changes in the taxation and superannuation systems as everyone will be expected to play a role in the economic recovery. However, a substantial slice of the burden will likely fall on the shoulders of high-income earners in addition to that already being borne by landlords not classified as high-income earners.

Likely tax options for repaying debt

Assuming the current bipartisan support shown to date in quickly passing stimulus packages through Parliament, two obvious reform options likely to pass relatively unchallenged would be the unwinding of the legislated personal income tax cuts and the revival of the ‘Budget Repair Levy’.

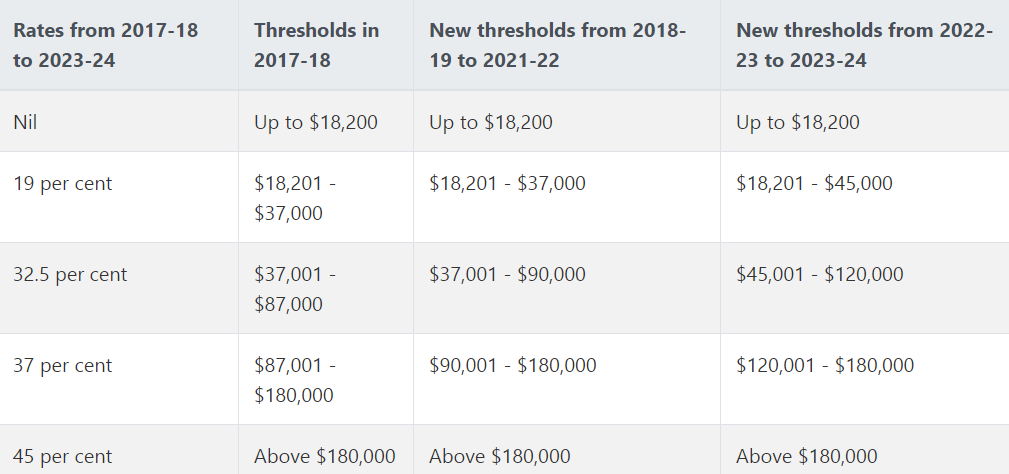

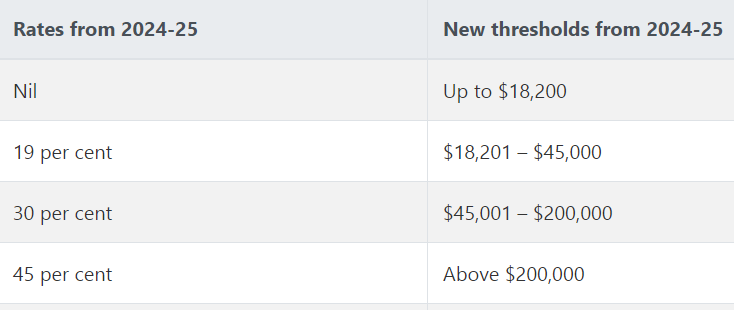

First, in the 2019-20 Federal Budget, the Government stated that ‘disciplined financial management’ has allowed it to enhance the ‘Personal Income Tax Plan’, providing a further $158 billion of further tax relief to most Australians. Clearly, the underlying premise for this policy has changed quickly and dramatically. Under the current plan, in 2022-23, the 19% threshold will increase from $37,000 to $45,000 and the 32.5% threshold will increase from $90,000 to $120,000. Then, in 2024-25, the 32.5% marginal tax rate will reduce to 30% and the top threshold will increase to $200,000 and the 37% tax bracket will be abolished as outlined in the tables below.

Source: 2019-20 Budget documents

The result would be a simpler system comprising three tax rates and a better alignment between the middle tax bracket and the corporate tax rate of 30%. The Government claims these changes will maintain a progressive income tax system, improve incentives for working Australians and contribute to a strong economy. However, pandemic-induced budget deficits bring the affordability of these measures into question.

Second is the resurrection of the ‘Temporary Budget Repair Levy’ brought in to address budget deficits incurred in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. That tax applied at an additional rate of 2% to personal taxable incomes in excess of $180,000 per annum and lasted from 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2017. The levy was expected to affect 2.3% of taxpayers with taxable incomes in excess of $180,000 (around 400,000 taxpayers) and raise $3.1 billion. This option is relatively easy to implement quickly and could apply from as early as 1 July 2020.

Superannuation also a target

Another option is to cancel the legislated increase in the superannuation guarantee charge (SGC) rate. The current 9.5% rate is legislated to increase to 12% by 2025 in a series of annual steps as outlined in the table below.

Source: ATO

Some, including the Grattan Institute, have strongly argued against this increase on the basis that it effectively comes out of employees’ earnings. Putting that argument to one side, cancelling this increase would ease the financial impact on many businesses and may provide incentives for them to hire additional employees.

Another option might be to tap superannuation funds, despite the $3 trillion held in super before the crisis taking a beating due to stock and bond market declines. This could take the form of an increase in the current concessional tax rate of 15% on fund earnings or even the reintroduction of taxes on certain benefit payments.

Currently, pensions and lump sum withdrawals from the superannuation environment are tax-free to those over 60 years-of-age from funds that pay tax. An argument could be mounted on equity grounds that it is only fair this cohort shoulder some of the financial burden.

Ability to introduce unpopular measures

There is a saying in politics ‘don’t let a good crisis go to waste’, and in times of crisis the Government may be forced to implement otherwise unpopular measures in the best interests of all Australians. These reforms may even include some of the politically unpalatable options put forward by the Labor party in the lead up to last year’s federal election.

Those measures included, among others:

- limits to negative gearing

- halving of the capital gains tax discount (from the current 50% to 25%)

- eliminating the refundability of franking credits.

The Parliamentary Budget Office had costed the first two measures to raise $35 billion over the next decade while the policy regarding franking credits was estimated to save $59 billion over the decade. These reforms were discussed extensively in Firstlinks and in the wider public domain and arguably had a significant role to play in Labor’s poor election result.

Nevertheless, given we are in uncharted waters, it is possible that the potential to raise large amounts of revenue from these reforms, some could be resurrected by the Coalition Government, albeit in modified form, under the guise of fiscal necessity.

It may also be possible that the most profitable companies will be expected to shoulder a slice of the burden. This should come as no surprise since the Federal Government has focused on supporting businesses during the crisis by relaxing stringent insolvency laws and through the provision of a wage subsidy. Therefore, additional options may be on the table, such as the imposition of a ‘super profits tax’ on the most profitable companies. This would take the form of an additional tax on top of the 30% corporate rate paid by larger companies. However, such a measure would be relatively pointless if it is not implemented in combination with a partial or full scale back of the refundability of franking credits.

Other potential reforms have not been discussed on the basis that they would simply be too politically unpalatable. These include increasing the rate of the GST to bring our system more into line with those of like nations such as NZ (15%) or the UK (20%) or eliminating some of the exemptions currently available, or the introduction of an inheritance tax similar to that in place in the UK.

Be prepared for hits

The Federal Government will face a delicate balance between raising much-needed revenue to manage the extraordinary budget deficit while providing enough incentive and stability in the economy in the post-coronavirus world. No doubt, financial planners are currently focused on assisting their clients navigate the myriad of Government financial assistance on offer, plunging portfolio values and uncertainty around income in the short term.

This is definitely the right approach for now. However, the key message for advisers in this article is that they should also keep an eye on what may eventuate in the medium term so they can be on the front foot if the tax-related darkness at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel arrives as expected.

Dr Rodney Brown is a Lecturer at the School of Taxation and Business Law (incorporating Atax) and a member of the Centre for Law Markets & Regulation at UNSW Business School. This article is based on an understanding of the rules at the time of writing.