Many retail investors are drawn to invest in emerging market funds, but think little about which countries they are investing in? Emerging market indices are poor representations of the investment opportunities available in that asset class. This arises in part because the index includes countries which are no longer emerging and omits some which manifestly are.

Readers would have no problem naming countries considered ‘core’ emerging markets: China, India, Brazil, Mexico. Others would utilise the ‘BRICs’ misnomer. But how about Vietnam? Or Israel? Or Taiwan?

It’s difficult to compile a definitive list of which countries qualify as ‘emerging markets’ and which do not. The methodology for including countries in the index is far from academic. Investors in emerging markets, and particularly retail investors purchasing exchange traded funds which mirror the index, have a particular conception of what they’re buying: access to markets where, in theory, there is scope for higher returns if investors are willing to tolerate the potential for higher risk.

Investors in the asset class typically seek to benefit from the tailwinds around hundreds of millions of people being lifted out of poverty via globalisation, through the allocation of capital to companies which are contributing to and benefiting from sustainable development.

Yet this is hardly a truthful representation of the constituents of the index. Most prominently, South Korea and Taiwan are not countries characterised by youthful populations, rapid urbanisation, a shift from agriculture to industry and an emerging consumption-driven middle class. They went through those transitions years or even decades ago.

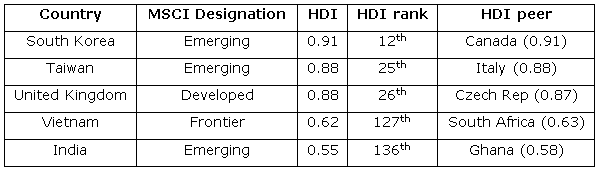

Rather, these are societies where the median age is higher than the US, GDP per capita is higher than Italy and life expectancies match those of Denmark. On the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) from March 2013, both are very firmly ‘very high human development’ societies. Indeed, both have levels of human development higher than that of the UK.

Yet emerging market indices typically allocate a quarter of their assets to Taiwan and South Korea, countries not yet reclassified as developed markets based purely on the basis of technicalities around market access.

Meanwhile emerging markets investors struggle to access large developing country markets like Vietnam, Nigeria and Bangladesh, which are quickly integrating themselves into the global economy and ‘emerging’ as viable, long-term investment destinations. These ‘frontier’ countries are firmly emerging markets in socioeconomic terms.

This situation results in investors missing out on long-term investment opportunities. Equally, those countries excluded by emerging market indices are overlooked for portfolio flows which can help contribute to long-term socioeconomic development.

This is only one, albeit pertinent, example of the absurdity of investing according to an index, for the simple reason that they are necessarily backwards looking. Both in terms of companies and countries, they are composed of yesterday’s winners, not tomorrow’s. Investing through indices is akin to driving along a road by looking in the rear view mirror.

The concept of exchanges falling into categories such as developed or emerging is a diminishing cogent notion. It is becoming increasingly easy for companies to choose the location in which to list, such as Chinese entities in New York or Russian companies in Hong Kong. More and more businesses are now truly global, and are either listed in developed markets but derive a significant to large portion of earnings from emerging markets, or vice versa.

The index thus bears little resemblance to the opportunities available to investors in emerging markets. This is especially so when the indices include countries which no longer benefit from the strong sustainable development tailwinds that are expected to be the driver of potentially higher returns in emerging markets whilst excluding some which do.

Bottom-up stock-pickers should not be hamstrung in searching for returns for their clients by arbitrary indexes. The fact is businesses do not run themselves in line with indexes so therefore asset managers should not feel the need to allocate capital or define risk on such a basis.

Jack McGinn is an Analyst with First State Stewart, part of Colonial First State Global Asset Management, specialising in Asia Pacific, Global Emerging Markets and Global Equities funds.