Over the next decade, we believe investors will face a world of deglobalisation, debt and disorder. The relative stability and strong investment returns of the post-Cold War era may well be coming to an end.

Deglobalisation began after the global financial crisis. It is now accelerating as the US and China try to decouple their economies and appear likely to continue to do so, driven by economic nationalism.

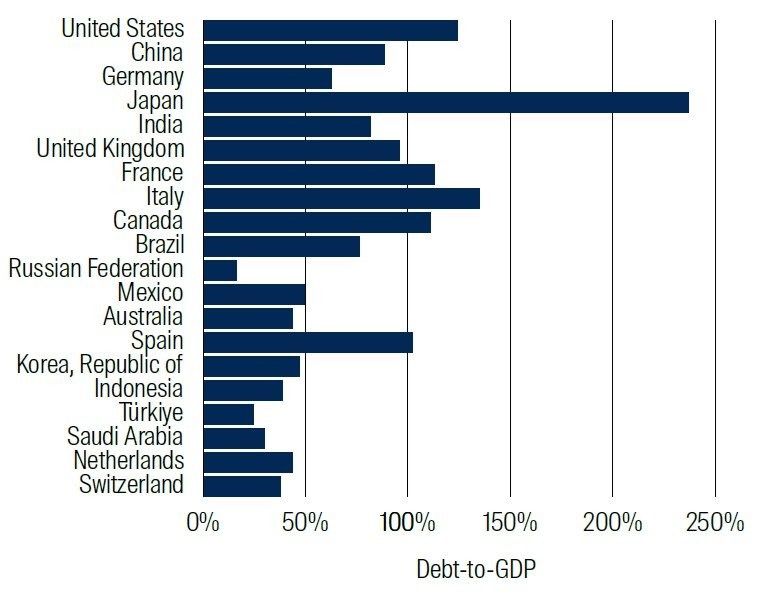

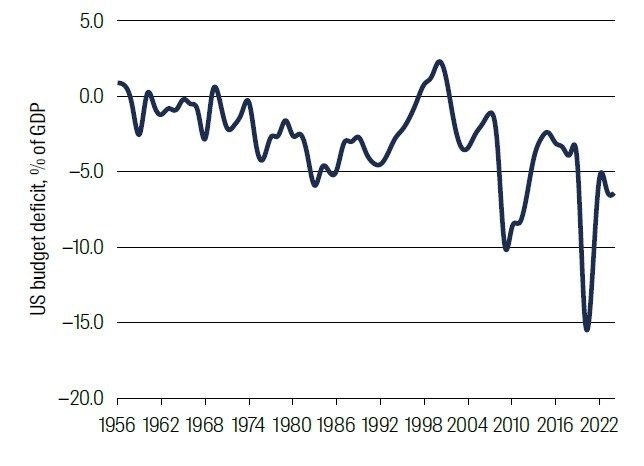

The western world is mired in unprecedented (for non-wartime) government debt levels, with politicians globally seemingly addicted to fiscal deficits. The world’s next debt crisis appears likelier to emerge from within developed markets than from – historically the more prone – emerging markets.

The problems caused by deglobalisation and high indebtedness will likely be amplified by disorder in the global political economy, stemming from nationalism, populism, intergenerational conflict, corruption, hybrid warfare and a return to great power conflict, with Russia and China each seeking to re-establish their former empires.

Deglobalisation, debt and disorder will have an adverse effect on the risk/return equation for investors. Risks will increase, impacting equity risk premiums, interest rates and foreign exchange rates. At the same time, we believe returns will be negatively impacted by lower economic growth rates, rapidly changing operating environments, increased government intervention and higher volatility in corporate earnings.

Just as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 resulted in a ‘peace dividend’ for investors, this new world order now appears likely to lead to a lower return, higher risk investment environment.

Within this new world order, society’s demand for new, improved or replacement infrastructure remains strong across both developed and developing countries. Whether you are a populist, nationalist, socialist, centre-left or centre-right politician, better infrastructure is on your agenda. Countries may now be turning inward from globalism to nationalism. However, investment will still be needed to replace aged infrastructure, expand urban development and provide a backbone for the structural growth of the digital economy.

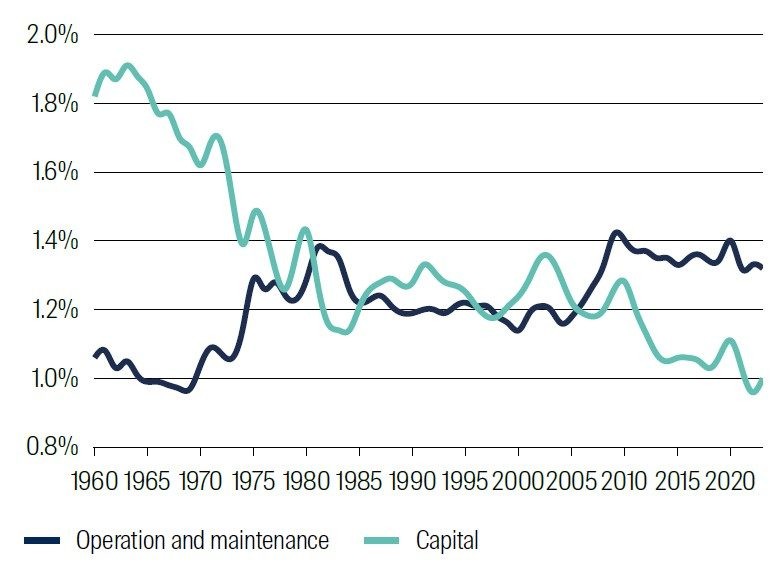

What is changing is governments’ ability to fund infrastructure investment. Large fiscal deficits – leading to higher debt levels, leading to slower economic growth – mean that governments will be less able to fund infrastructure investment in the future.

Hence, we believe that private sector capital will play a larger role in infrastructure investment going forward. This means governments will need to provide attractive investment frameworks to entice increased capital to develop new infrastructure. The United Kingdom’s water utilities and electricity utilities in Texas are already seeing improvements to their respective investment frameworks.

A growing role for private sector capital in infrastructure could include the privatisation of existing government infrastructure. While not politically popular, fiscal reality is already biting in many parts of the globe. In the past two years we have seen the listings of Tokyo Metro and Athens Airport; several new Managed Lane projects in the United States; toll road privatisation in Brazil and the development of new privately owned and operated airports in India.

We have also noted with interest that where governments have had the opportunity to nationalise infrastructure assets over the last few years (high profile examples include listed electric utility PG&E in United States, and unlisted water utility Thames Water in the UK), they have declined to do so. We believe this is partly due to not wanting to add to existing public finance pressures and partly not wanting government to take responsibility for these difficult, politically sensitive assets.

The global listed infrastructure asset class is well equipped to live, thrive and survive in a world of deglobalisation, debt and disorder. These assets are foundational to modern economies and societies, making them indispensable regardless of geopolitical or macroeconomic conditions. Infrastructure assets’ strong pricing power, high barriers to entry, structural growth and predictable cash flows provide investors with defensive growth.

Deglobalisation is likely to cause disruption across the global economy; and to result in lower economic growth rates. These are both negative factors for equities’ earnings growth. In contrast, infrastructure’s essential service nature should help to shield it from the disruptive and dampening effect that deglobalisation has on economic activity levels.

High governments debt levels are also likely to weigh on economic growth and to lower long-term interest rates. Historically, high debt burdens have tended to constrain a country’s economic growth rate. This in turn lowers earnings growth potential and valuation multiples – more so for equities than for global listed infrastructure. High debt levels are also likely to reduce the long-term neutral interest rate level required to manage debt serviceability. This phenomenon has been observed in Japan and in parts of Europe. Lower long-term interest rates tend to favour interest rate-sensitive asset classes, including global listed infrastructure.

A disorderly, less predictable and more fragmented world will adversely affect all investments. This is because investors value predictability and growth; and prefer to avoid volatility.

In this situation, global listed infrastructure’s essential services provide a relatively high level of predictability. No matter how disordered the world becomes, infrastructure’s electricity, natural gas, water, cell phone, waste collection service, toll road or airport will remain in demand.

Business models have never been more robust

Moving from a macro to a more micro level, the underlying business models of global listed infrastructure have never been more robust during the 20 years the asset class has existed than now.

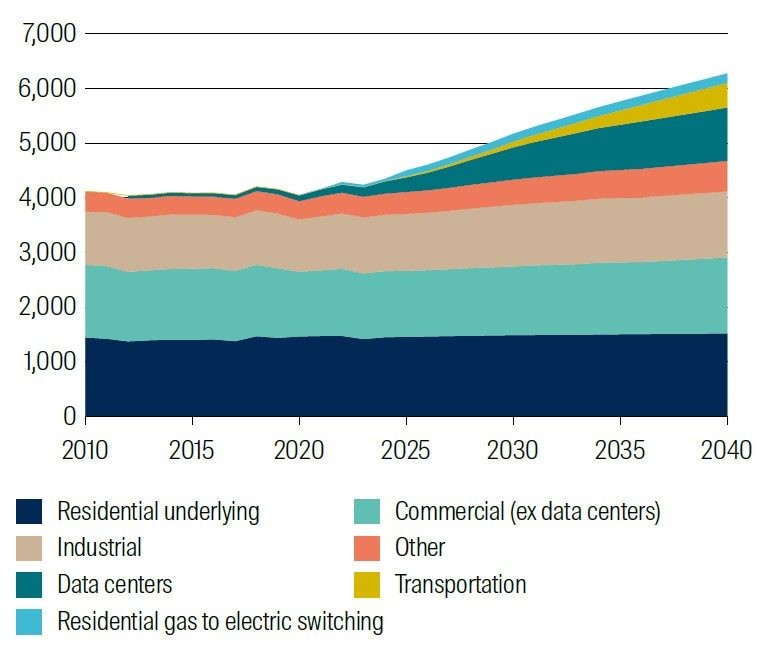

Starting with utilities, especially electric utilities; the demand, investment and earnings growth outlook for the next decade is accelerating. This is due to a number of structural factors including:

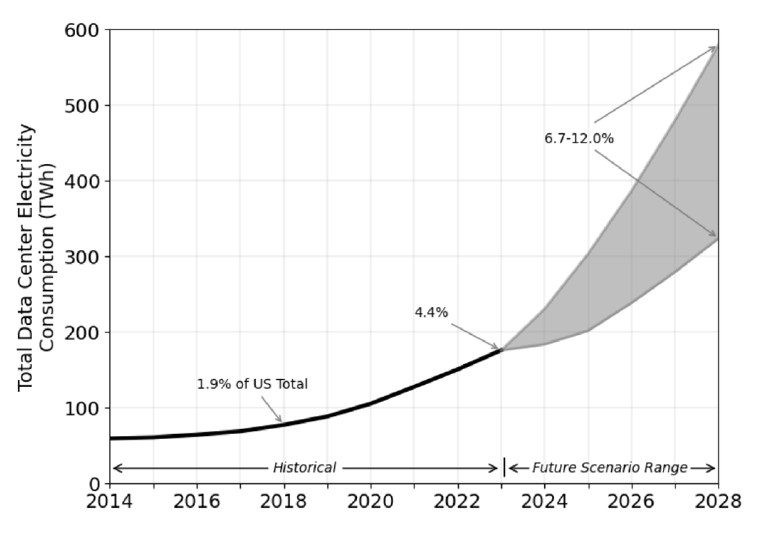

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) -driven data centre expansions,

- the electrification of transportation,

- the electrification of buildings,

- gas-to-electric switching and

- further decarbonisation of the electricity generation fleet (coal-to-gas-to-renewables-to-nuclear).

Not only is the growth outlook for electric utilities accelerating, but regulatory risk is also reducing. This is a reflection of the urgent nature of current demand growth, which makes regulators (and their political masters) more positively disposed towards paying a fair return on investments which bring economic development (and employment opportunities for voters).

The outlook for investment opportunities related to digital infrastructure (mobile towers, data centres and fibre) is also robust. The mobile tower industry is progressing with the installation of 5G equipment, as network operators seek to improve and increase their coverage to support consumer mobility of audio and video data. The next step change will likely come from new demand being driven by the Internet of Things and autonomous vehicles. Data centre growth is accelerating, driven by the early stages of the AI industrial revolution. Given the copious amounts written elsewhere on this topic, I will not expand on this point in this paper.

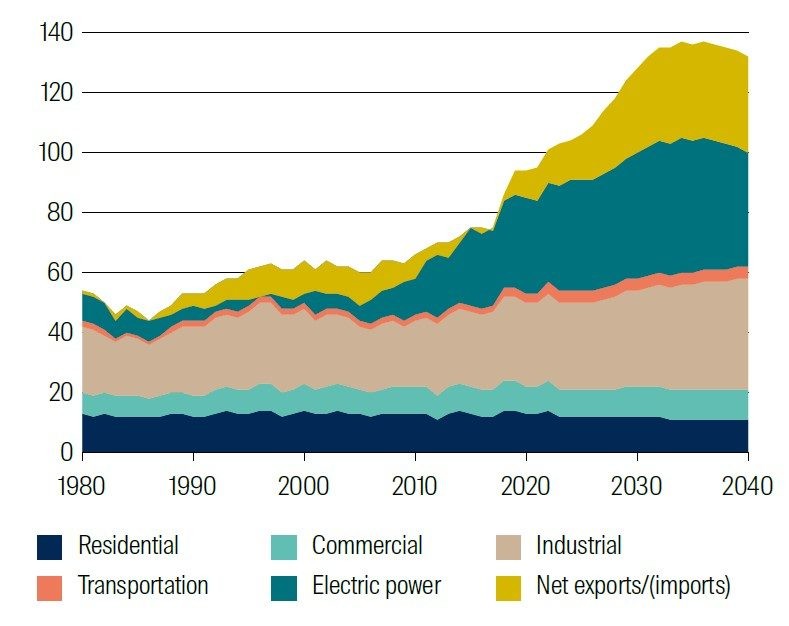

The North America-focused, historically cyclical energy midstream sector (oil and natural gas transportation and storage assets) appears well-positioned to deploy capital to support the demand growth for natural gas. Demand is being driven both domestically, for consumption within the United States, and from overseas, as natural gas exports from the US and Canada displace (1) Russian energy in the western world and (2) coal in the developing world.

Transport infrastructure (toll roads, airports, railroads) appears set to benefit from several structural tailwinds to investment over the next decade. Toll roads represent the outsourcing of taxation by highly indebted governments to deliver the new road capacity that is needed for urbanisation and economic development in the developing world and for congestion reduction in the developed world. While toll roads are not popular with voters, politicians appear unable to raise taxes to replace these “user-pays” assets, i.e. toll roads are the lesser of two evils.

Airport investment has restarted after a COVID-driven pause, with the popularity of leisure travel defying the deglobalisation trend. We believe that above-GDP growth in leisure travel in the developed world is being driven by the generational tailwinds of baby boomers’ wealthy retirement and Gen Z fear of missing out (FOMO). In the developing world, we expect continued strong growth from the emerging middle class.

Railroads – both freight and passenger – remain in a long-term market share fight with trucks and airlines but have structural advantages over both in terms of lower costs, lower carbon emissions, strong community acceptance and larger automation advantages.

In the almost 20 years that our team has been researching global listed infrastructure, we have never been so optimistic about the current business models and future growth prospects of the asset class. In contrast to different points over the past decade, no-one today is contemplating the utility death spiral, stranded asset risk owing to natural gas being phased out by 2030, or toll roads being disrupted by flying cars.

Higher earnings growth and lower relative risk?

Over the next decade we believe the global listed infrastructure asset class can deliver higher earnings growth to investors, despite a lower growth world of deglobalisation, debt and disorder. Our confidence in this view is based on the bottom-up, structural growth drivers of infrastructure’s various subsectors listed above.

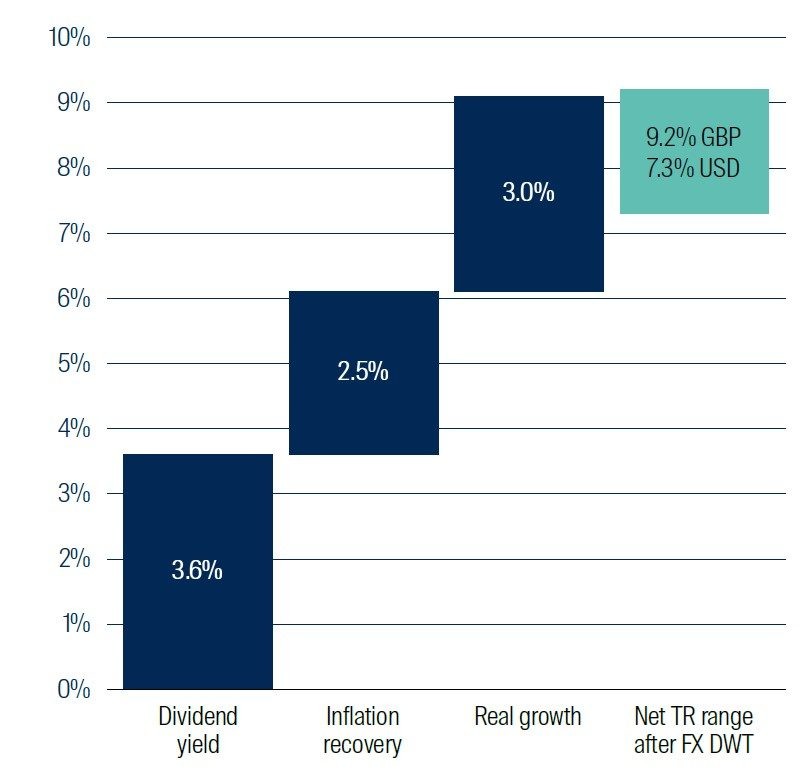

We believe that through the cycle, asset class fundamentals support Earnings Per Share growth of between 5% and 6% per annum, plus a dividend yield of between 3% and 4%, giving what we believe is a highly competitive total return of between 8% and 10% per annum.

In addition to delivering robust returns, we believe that risks for global listed infrastructure can be relatively lower in a world of deglobalisation, debt and disorder. This lower risk comes from a societal demand for improved infrastructure. Nationalism means a more domestic focus, which means more infrastructure investment. Political and regulatory risk for electric utilities and energy midstream are reducing, owing to higher economic development demands being driven by data centres and by national security concerns.

In addition, rising government debt means that governments will increasingly need to rely on private sector capital. As a result, they will face increased pressure to offer a favourable investment environment, with attractive and predictable risk-adjusted returns.

Conclusion

The global political economy is rapidly evolving. The next decade is likely to be characterised by deglobalisation, debt and disorder.

Despite a slower growth, higher risk global economic environment, we believe global listed infrastructure can deliver higher earnings growth with lower relative risks, enhancing the appeal of the asset class relative to bonds or equities.

Global listed infrastructure’s defensive growth characteristics and improving demand outlook see it well-positioned to deliver attractive risk-adjusted returns to investors.

Andrew Greenup is Deputy Head of Global Listed Infrastructure at First Sentier Investors (Australia) Ltd, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This material contains general information only. It is not intended to provide you with financial product advice and does not take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from First Sentier Investors, please click here.