I have been stunned for many years by Tesla’s market capitalisation. At US$291.00 per share, Tesla is valued by the market at US$50 billion ($69 billion).

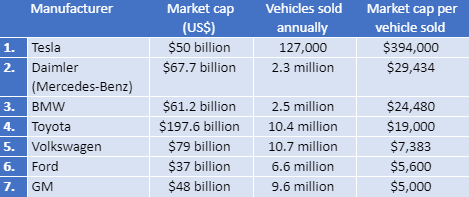

Manufacturing and quality control issues, longer delivery times, and the antics of the CEO aside (please stay away from Twitter, Elon), Tesla delivered only 126,740 vehicles in the year to 30 June 2018. That’s a market capitalisation of US$394,500 per vehicle. To put that in perspective, Ford Motor Company sits on a market capitalisation of US$37 billion ($51 billion) and delivered 217,700 vehicles worldwide in the month of August alone. In 2017 Ford sold approximately 6.6 million vehicles worldwide. That equates to a market capitalisation per vehicle of US$5,600.

Over in Europe, Volkswagen AG trades on a market capitalisation of €68 billion (US$79 billion), which puts it on a market capitalisation per vehicle of $7,383 given it sold 10.7 million vehicles in 2017. Only the luxury brands such as Daimler and BMW trade on market caps of more than US$20,000 per vehicle sold and even then, they are more than 10 times cheaper than Tesla.

Market madness, or a transformative approach to market valuation

The following table summarises the price investors are willing to pay, per vehicle sold, for each manufacturer. Market caps are converted to US dollars.

Investors can buy GM for $5,000 per vehicle sold, or they can buy Tesla for nearly $400,000 per vehicle sold. The economics between Tesla and every other car manufacturer in the world, in the long run, might be slightly different but they cannot be sufficiently dissimilar to justify such a disparity.

Clearly, enthusiasm for the world-changing potential of EV technology has translated to an equally-transformative approach to stock market valuation. What investors are forgetting however is that Tesla will ultimately be a car company.

Since the horseless carriage was invented by Karl Benz, there have been more than 1,500 car manufacturers in the United States of which only one exists today – Ford - that makes a profit and was not bailed out by the US Government during the GFC. Changing a drive train from petrol to electric will not miraculously alter the economics of the business of making and delivering cars. Ultimately, if it survives, Tesla will be making cars, which is a highly labour- and capital-intensive fashion item where tastes for colours and styles change just as frequently as on the catwalk. Oh, and Ford plans to invest US$11 billion in electrification by 2022.

The same nutty logic is applied in Australia

While Tesla has not distracted me from the harsh realities of competitive business dynamics, it has distracted me from the fact the same insanely optimistic, if not just plain nutty, logic is being applied to high potential growth companies here in Australia. Let’s not forget this is purely a function of cheap interest rates and inflation-free growth that simply won’t last.

But more importantly, investors here in Australia are forgetting that the new businesses – even those that promise an exciting theme and a ‘global’ opportunity - aren’t really new at all. Yes, in some cases they are signing up customers at a rapid rate, but ultimately, it is growth in profits not ‘users’ that counts. If they survive competition, they are more than likely to be a business with vastly similar economics to those they disrupt. There are no free lunches.

Take a look at the market capitalisations of some of Australia’s listed businesses whose share prices have rallied on the back of hopes of global domination; A2 Milk, Afterpay Touch, Xero, Wisetech Global, Altium and Appen have an aggregate market capitalisation of $31 billion, combined revenue of less than $2 billion and combined net profits of just $240 million. Of that profit, A2M is responsible for $185 million and Xero and Afterpay Touch are losing money.

An equally-weighted portfolio of the above companies is trading on 129 times earnings. Yes, value investors tend to get a bit grumpy when the optimists are winning but it is not unexpected to see party revellers having a great time during the party. It’s the morning after when heads hurt.

Afterpay builds in massive growth hopes

Afterpay Touch is a classic example of a company that has benefited from a hopeful approach to valuing growth. I cannot count how many times I have heard “if they can grab just X per cent of US retail sales, they’ll be worth … X to the power of …”. It’s a good rule of thumb to zip up your wallet when a promoter includes in their slide deck the size of a market, and then asks you to consider what would happen if they ‘only’ take one per cent.

Afterpay is effectively providing a small and short-term (roughly 56 days) line of credit on an average transaction value of $150. When interest rates are zero and credit is cheap, consumers love borrowing money and consequently consumption surges. It’s a combination that, in the absence of disruption, represents Goldilocks conditions for retailers and consumer finance companies.

The only problem of course is that when interest rates rise consumer finance companies are hit, not only by rising bad and doubtful debts but slowing consumer conditions too. Margins are squeezed between slumping revenues and rising costs. It wasn’t so long ago that Afterpay was trading at less than $3.00, and today its shares are more than five times higher at $17.00.

Afterpay earns its money by charging consumers $10 if they miss a payment plus another $7 if they are more than a week late (the maximum cumulative penalty is $68), and by charging the retailer a few percent from each sale. Afterpay generates 75% of its revenue from retail merchant fees and about 25% from the customer via late fees, which jumped 364% in 2018.

As I mentioned earlier, many of these new age businesses and ‘digital disrupters’ aren’t that new at all. Afterpay looks very similar to a factoring business, just as Tesla looks scarily like a car manufacturer.

When a business wants to receive cash flow, one of things it can do is sell its receivables at a discount. In a factoring arrangement, a business makes a sale and generates an account receivable. The ‘factor’ buys the right to collect on that invoice (the receivable) by agreeing to pay the seller the invoice's face value, less a fee. Sound familiar? It’s exactly what these retail finance offerings are. A merchant is selling the goods today to a customer who hasn’t yet paid, and is instead receiving a discounted payment from the finance provider – the ‘factor’, in this case Afterpay.

And because the factoring businesses extends its credit to the clients' customers, rather than the client, it’s concerned about the credit risk of the customers, not the client. The client is laying off the risk of non-performance to the finance provider. Factoring is one of the oldest forms of finance available and the economics of factoring businesses aren’t particularly attractive because factoring is not a particularly high-return business.

There is a basic relationship in investing that has always held true. High returns usually come from assuming higher risk. So how can investors in Afterpay generate high returns from what is effectively a low-return factoring business?

Some professional investors might argue that the returns from Afterpay’s factoring business are in fact high and the risks very low because small individual amounts are being assumed and the terms are short at 56 days. But if that were true, how is Afterpay able to extract such high returns when extending credit to low risk customers?

If such great returns are available from extending credit to very low risk customers, others will join the party. And that is something both Afterpay and Tesla investors seem to have missed.

Roger Montgomery is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at Montgomery Investment Management. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.