The goal of equity fund investors should be to identify and stay with top-performing managers over the long term (5-10+ years). Data shows that virtually all long-term top-performing managers have shorter term periods (1-3 years) where they underperform their benchmark, but ditching managers at the first sign of underperformance is likely to be a suboptimal strategy.

Too much focus on the short term

The financial media love to laud or lament short-term investment performance, both good and bad. As an investor, it’s easy to get drawn in and mentally extrapolate out recent trends across your portfolio.

But to capture superior long-term results, which is what most investors ultimately aim for, periods of short-term pain must be tolerated.

These short-term swings can be difficult to stomach and will often tempt investors to bail out of the market. However, without being able to accept periods of underperformance, investors may miss the market’s inevitable rebound and fail to harvest the long-term superior returns of equities.

If investors can develop a deeper understanding of how top funds perform over time, they will more confidently weather the inevitable periods of short-term volatility in performance, and be more likely to reach their long-term investment goals.

Don’t be alarmed

Almost every top-performing fund has instances where it underperforms its benchmark and its peers, particularly over time periods of three years or less.

A study by independent US investment bank, Baird, looked at a group of more than 1,500 funds with 10-year track records. They then narrowed the list to 600 funds that outperformed their respective benchmarks by one percentage point or more, on an annualised basis, over the 10-year period. The list was further narrowed to include only those funds that both outperformed and exhibited less volatility than the market benchmark.

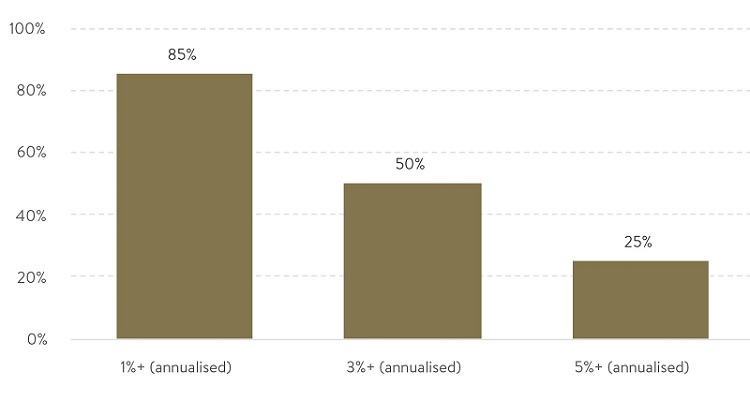

Percentage of top-performing funds that underperformed over any three-year period

Source: Morningstar, Baird Analysis

Despite their impressive long-term performance, 85% of these top managers had at least one three-year period in which they underperformed their benchmark by 1% or more. About half of them lagged their benchmarks by 3%, and one-quarter of them fell 5% or more below the benchmark for at least one three-year period.

Investors could have been alarmed by these periods of underperformance, yet in the long-run, it paid off to stay with the top performers over a 10-year time span.

It pays to be patient

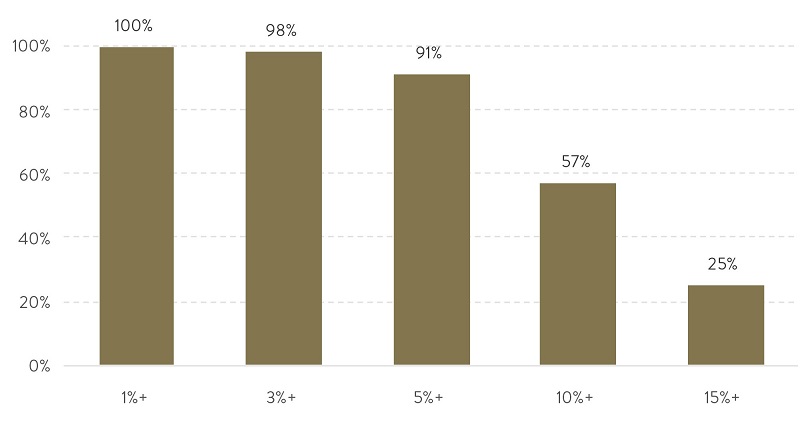

When looking at shorter periods, the results were even more telling. All the top managers dropped below their benchmark at least once. Moreover, one-quarter of them went through at least one 12-month period where they underperformed their benchmark by 15% or more.

Percentage of top-performing funds that underperformed over any 12-month period

Source: Morningstar, Baird Analysis

By these measures, all fund managers, including even the best, go through periods of underperformance. It is challenging to know what to do when a fund is in the midst of one of these tough periods but it pays to be patient. The longer an investor can wait, the better their funds' chances of beating its benchmark become.

Time diversification

One of the major factors affecting fund performance is the cyclical relationship between asset prices and the business cycle. In the short term, investments can fluctuate in value for a number of reasons, including changes in the economy, volatility, political uncertainty, business failures, interest rate changes, fluctuations in currency values, and company earnings. In an economic downturn, GDP growth slows, and business earnings decline, which leads to less optimistic outlooks for companies and lower stock prices. In an economic expansion, the reverse tends to happen.

But time is an investor’s best ally.

As investor holding periods lengthen, short-term risks tend to become less relevant, partly because many short-term price movements tend to offset each other over a complete business cycle. This means that, as an investment's holding period increases (such as 20 years versus five years), investment risk due to market volatility (ups and downs of prices) will decrease. Both the frequency and magnitude of underperformance become less dramatic over more extended periods.

Take an holistic view and reduce the churn

In our opinion, fund manager churn benefits no one, and hence at Ophir, we seek investors who agree with our investment philosophy and appreciate our process. We expect our portfolios to have negative years or underperform their benchmarks on occasions, and we understand that investors may feel uncomfortable through these periods. We prefer not to see investors buy into an Ophir equity fund based solely on a few quarters of strong returns if they are likely to reverse course and sell out when returns fall short.

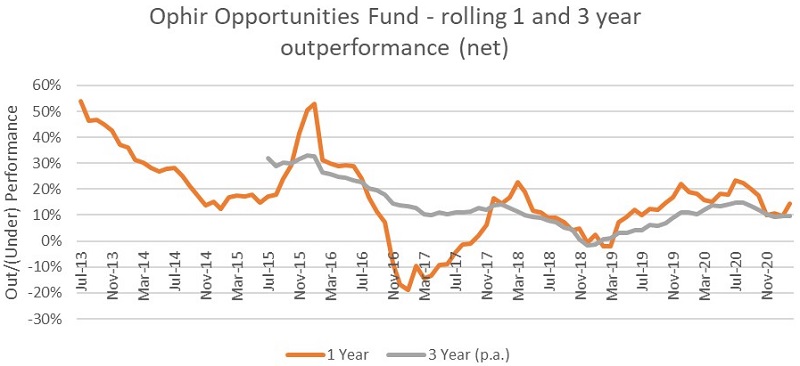

For example, as seen below, the Ophir Opportunities Fund, which has the longest track record of any Ophir fund at almost nine years, has had two periods of one-year underperformance and one period of three-year underperformance (albeit briefly), yet is the top performer in its class* over the long term, generating 24.6% p.a. (net of fees) since its inception in August 2012.

Source: Ophir Asset Management. *FE fund data, Australian Small/Mid Caps, Aug 2012 to March 2021

Investors should remain focused on their long-term financial plan and avoid knee-jerk reactions during times of negative absolute or relative performance. A more holistic view of managers needs to be taken. This includes factors such as long-term track record (if it exists), people, investment process, levels of alignment and adherence to capacity constraints, amongst others.

Andrew Mitchell is Director and Senior Portfolio Manager at Ophir Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

Read more articles and papers from Ophir here.