The sentiments of three-time world Formula One champion, Niki Lauda, live permanently in our minds: “From success, you learn absolutely nothing. From failure and setbacks, conclusions can be drawn.”

But what conclusions? What lessons? Indeed, what should even be measured to evaluate success, versus setbacks or failure?

Below are five unambiguous truths that will help investors answer these questions:

1. Think in terms of probabilities

We humans tend to guess what the future holds. And we can hardly be blamed. An increasing body of evidence from neuroscience suggests the human brain learns by constantly making predictions about the world, which are subsequently updated by what we observe.

But investing requires a different approach.

Rather than guessing what will happen, we are better off assessing what could happen. Then, for each of these possible scenarios, assessing the likelihood (or probability) of it happening.

This ‘probabilistic’ approach helps investors better understand, and frame, the calculated risks we take.

Contrast two of Montaka’s investee companies: Moderna and S&P Global, for example.

While both have merit as investment opportunities, they could not be more different in terms of their probability-weighted range of possible outcomes.

The range of possible outcomes for Moderna is very wide. If the company’s world-leading mRNA technology can be used not just for COVID, but also for the seasonal flu, RSV, and various personalized cancer vaccines, then the upside in shareholder value is multiples from current levels.

But these use cases are far from certain. And if Moderna’s vaccines prove to be ineffective, then there could well be significant downside in value from current levels.

Contrast this wide range of outcomes with a far narrower set of possibilities associated with S&P Global – a much more predictable business that is tied more to the size of the global economy. Growth is reliable, profit margins are stable and there are likely fewer surprises on the horizon.

This framing – characterized by the range and probabilities of possible outcomes – helps assess how much capital to place at risk.

Montaka’s investment in S&P Global is much more significant than its relatively small investment in Moderna. This limits downside potential, while still allowing for participation in meaningful upside scenarios.

2. Extend your time horizon

Students of finance theory are taught that businesses are valued on the cash flows they deliver to shareholders into perpetuity. And yet, well after they graduate, many of these students focus excessively on what the next 3, 6 or 12 months holds for a company … though this accounts for a tiny fraction of its total value.

Even today, many investors are focused on whether the Fed might change its policy rate by 0.25%, or not, in the coming days or weeks. Or whether the US will be in a technical recession over the next six months.

Many stock analysts spend a disproportionate share of their time analyzing last quarter’s results and forecasting the next.

This tends to lead to a subconscious overweighting of the importance of the near-term, at the expense of the much more important longer-term.

But the great investments are often determined by long-term realities (relative to expectations). While the short-term realities of the day turn out to be overwhelmingly irrelevant.

So how does an investor overcome this short-term bias? Extending one’s time horizon is an approach that delivers two key benefits to investors.

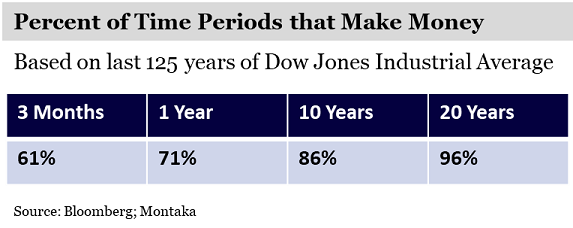

Firstly, it increases the probability that you will make money. The table below shows that the longer your time horizon, the more likely you are to make money investing in equities. Over the last 125 years, 96% of all 20-year periods have made money.

A second benefit to extending one’s time horizon is that it helps focus our attention on the most important things, such as competitive positioning and earnings power in 3-, 5- and 10-years’ time. (Or in more precise probabilistic speak: the ranges of possible competitive positions and levels of earnings power, coupled with their respective likelihoods).

3. Tune out the noise

A liberating benefit of a long-term focus is that the endless short-term gyrations in news flow and market movements become less relevant.

Of course, this is easy to say and hard to do. We are wired to overweight recent facts and over-update our prior forecasts based on the persuasive narrative of the day. But this is often a mistake.

As mentioned, businesses are valued into perpetuity. That is, present day value reflects all cash flows that shareholders are expected to receive, not just this year, but for the rest of time.

Investors should make a list of the really important long-term drivers of value and try to stay focused on these things. At Montaka, for example, we are focused on drivers including: (i) sources of advantages, and trajectories; (ii) current and future potential market sizes and sources of growth; (iii) unit economics of selling incremental products or services; and several others. And we continually evaluate these relative to expectations that are implied by current stock prices.

4. Run your own race

Many years ago, I was a national champion in the unusual sport of orienteering. And in orienteering, staying focused on your own race is vital to success.

When navigating through a forest, it’s tempting to follow the direction, or route-choices, of other athletes. But this can be very costly if they lead you along the wrong route – which inevitably happens. You always need to ‘run your own race’, even if it means making different choices to other athletes in the moment.

And it’s no different in the sport of investing.

There’s a saying in investing that: “If you aren’t misunderstood, you have no edge.” To invest well, you need to be different to the market, and you need to be right.

Why? Students of finance will be aware that stock prices are simply numerical representations of the set of expectations for the key value drivers of a business that are implied by the market. Therefore, if you expect what the market expects, it is already ‘priced in’ and you cannot outperform. Instead, you need to believe a different view to what the market believes (and you ultimately need to be right).

Of course, being different and misunderstood is often uncomfortable. But remind yourself: this discomfort is necessary.

5. Measure yourself objectively, and evolve

In a recent podcast, Professor John Vervaeke from the University of Toronto defined the concept of ‘implicit learning’ – learning that we aren’t aware is happening – that informs our intuition. “You’re picking up on very complex patterns without explicit awareness or deliberate effort,” he said.

The human brain continuously and subconsciously sharpens its intuition over time.

But there is a peril to this process, according to Vervaeke: “Implicit learning doesn’t care what patterns it picks up.” That is, the brain does not distinguish between real causal patterns, and correlational patterns.

You know how close to stand to somebody at a funeral, for example. You’ve picked that up somewhere along the way, though you don’t know where, when, or how. “So you just get the intuition,” sayd Vervaeke, “And you do it, and you’re right.”

But sometimes our honed intuitions are not right. Our ‘biases’ – including our overweighting of short-term information – are unambiguously flawed.

Unfortunately, the world of investing is flooded with complex correlational patterns that often lack true causal relationships. And stock prices are a big culprit.

Great analysis can frequently result in investment loss, particularly over short periods of time. Conversely, there are frequent instances of poor analysis resulting in investment gain.

This happens for several reasons. One relates to equity market inefficiencies – that is, deviations between stock prices and intrinsic value. Many factors drive these, from index funds, to monetary policies, and even social media.

Another simply relates to luck. Your analysis might suggest a 90% probability of gain, and 10% of loss – and you will lose one in ten times, by definition, despite the risk/reward ratio being fantastic. Alternatively, your loss – measured at a particular point in time – might simply reflect an unpredictable stock price journey over time towards an ultimate gain.

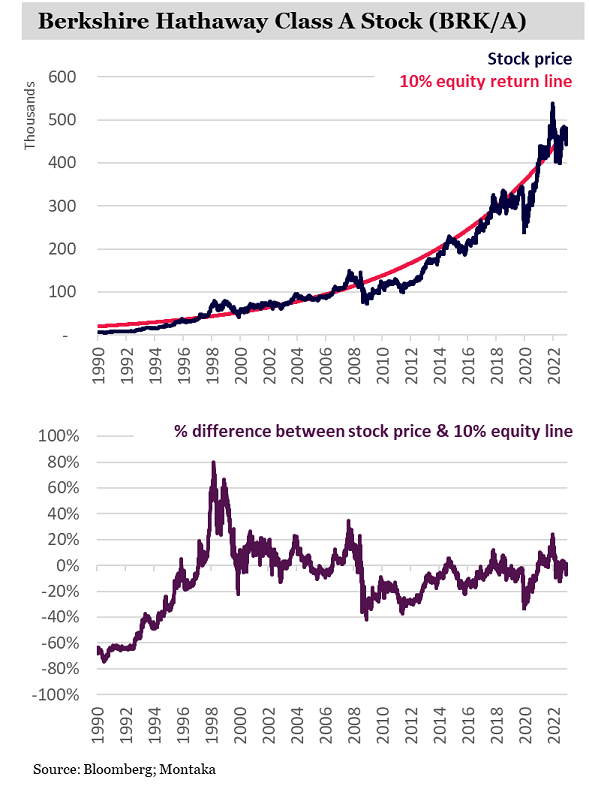

Take a look at the stock price of Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway over the last three decades below. If one were to assume that today’s price is fair value, and Berkshire investors typically expected an average 10% return each year, then we can infer the extent to which Berkshire was undervalued and overvalued over this time period.

Putting aside the precision of the above assumptions, what stands out clearly is that, even Berkshire Hathaway – one of the world’s most widely-followed and highest quality businesses, experienced periods of over/undervaluation that were both significant and persisted for years at a time.

The implication of these observations, therefore, is that investors are at considerable risk of learning the wrong lessons from time to time.

The solution here, according to Vervaeke, is to measure yourself with clear, objective, measurable information that is tightly coupled between cause and effect. Measure your fundamental forecasts (taking into account your assessment of possibilities and probabilities), not stock price returns, for example. Measure your adherence to process.

All investors are on a journey. Just keep evolving.

Andrew Macken is the Chief Investment Officer at Montaka Global Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and is based on an understanding of current legislation.

For more articles and papers from Montaka, click here.