With everything happening in the world — from the US push to annex Greenland, to new tariffs against Europe, to military intervention in Venezuela — investors may not be focused on the US midterm elections just yet. But this pivotal contest is just 10 months away, and the campaign starts in earnest next month when President Donald Trump delivers the State of the Union Address.

“Trump will use the State of the Union, where he commands a massive audience, to kick off the 2026 campaign,” says Capital Group political economist Matt Miller. “He will lay out a narrative and policy agenda designed to help the Republican Party defy the normal setback that we would expect to see for a president in the midterm elections.”

The key question for investors is: How might the midterms influence the stock market?

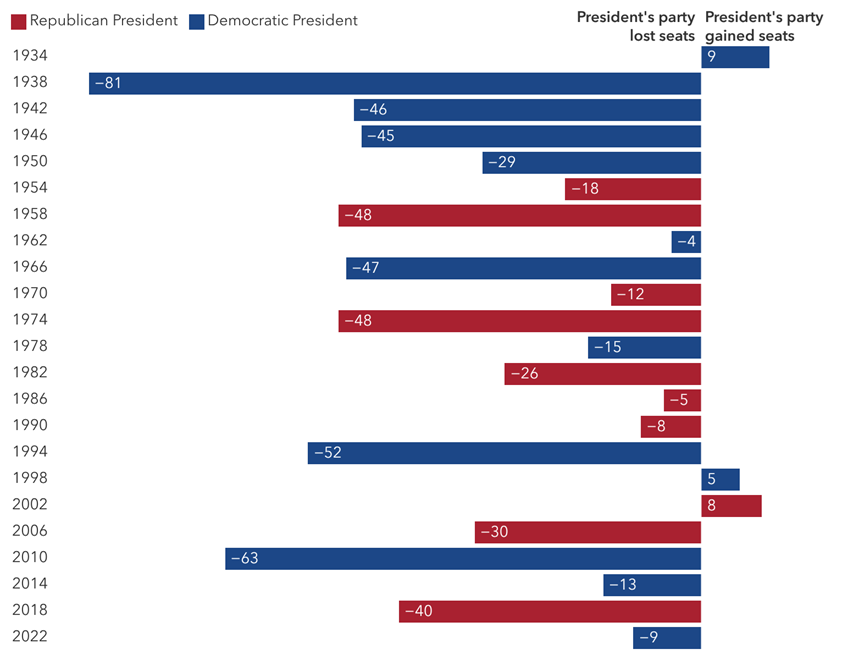

Figure 1: The president’s party typically loses seats in Congress

Net change in House of Representatives seats controlled by president’s party after midterm elections

Sources: Capital Group, UCSB: The American Presidency Project. As of 15 January 2026.

Midterm elections occur at the midpoint of a presidential term in November, and usually result in the president’s party losing ground in Congress. Over the past 23 midterm elections, the president’s party has lost an average 27 seats in the House of Representatives and three in the Senate. Only twice has the president’s party gained seats in both chambers.

This tends to happen for two reasons. First, supporters of the party not in power — in this case, the Democratic Party — usually are more motivated to boost voter turnout. Second, the president’s approval rating typically dips during the first two years in office, as it has with Trump, which can influence swing voters and frustrated constituents.

Republicans currently control both the Senate and House by slim margins. Losing either chamber would effectively end any chance to pass ambitious Republican-sponsored legislation over the next two years, and it would put Trump on the defensive for the remainder of his term in office, Miller explains.

Since losing seats is so common, it is usually priced into the markets early in the year. But the extent of a political power shift and resulting policy impacts remain unclear until later in the year, which can explain other interesting trends.

History suggests lower returns and higher volatility

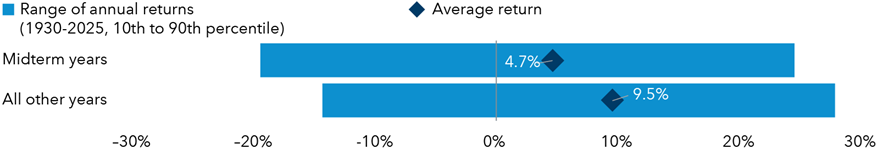

Capital Group examined more than 90 years of data and found that markets tend to behave differently during midterm election years. Our analysis of returns for the S&P 500 Index since 1930 revealed that the path of stocks during midterm election years differs noticeably compared to other years.

Since markets have typically gone up over long periods of time, the average stock movement during an average year should steadily increase. But we found that in the initial months of midterm election years, stocks have tended to generate lower average returns and often gained little ground until shortly before the election.

Figure 2: Market returns have lagged in midterm election years

S&P 500 Index total returns

Past results are not a guarantee of future results.

Sources: Capital Group, RIMES, Standard & Poor's. As of 15 January 2026.

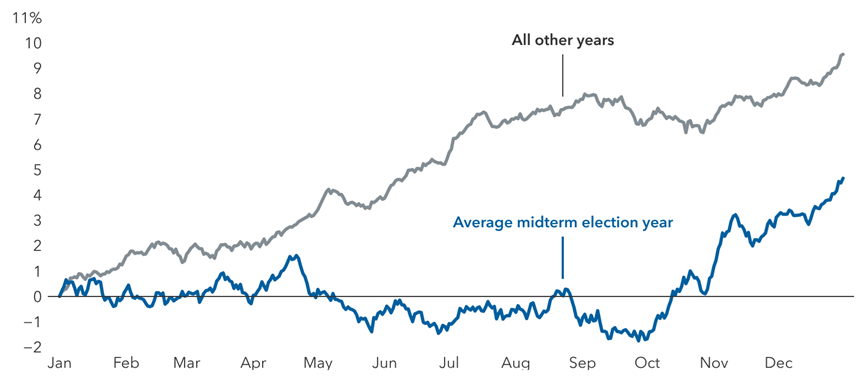

Markets do not like uncertainty — and that adage seems to apply here. Earlier in the year, there is less certainty about the election’s outcome and impact. But markets have tended to rally in the weeks before an election, and they have continued to rise after the polls close.

In 2025, the S&P 500 Index enjoyed a solid return of nearly 18%; however, it significantly lagged other major markets around the world. The MSCI Europe Index returned more than 35%. The MSCI Japan Index gained 24%. And the MSCI Emerging Markets Index was up nearly 34%.

Despite election-related uncertainty, investors should consider the cost of sitting on the sidelines or trying to time the market. Historically speaking, staying invested has been the smartest move. The path of stocks varies greatly each election cycle, but the overall long-term trend of markets has been positive.

Figure 3: Political uncertainty has dampened returns in midterm years

S&P 500 Index average returns since 1931

Past results are not a guarantee of future results.

Sources: Capital Group, RIMES, Standard & Poor’s. The chart shows the average trajectory of cumulative price returns for the S&P 500 Index throughout midterm election years compared to non-midterm election years. Each point on the lines represents the average year-to-date return as of that particular month and day, and is calculated using daily price returns from 1 January 1931 to 31 December 2025.

That said, there is no question that election season can be tough on the nerves. Candidates often draw attention to the country’s problems, and campaigns regularly amplify negative messages. Policy proposals may be unclear and often target specific industries or companies.

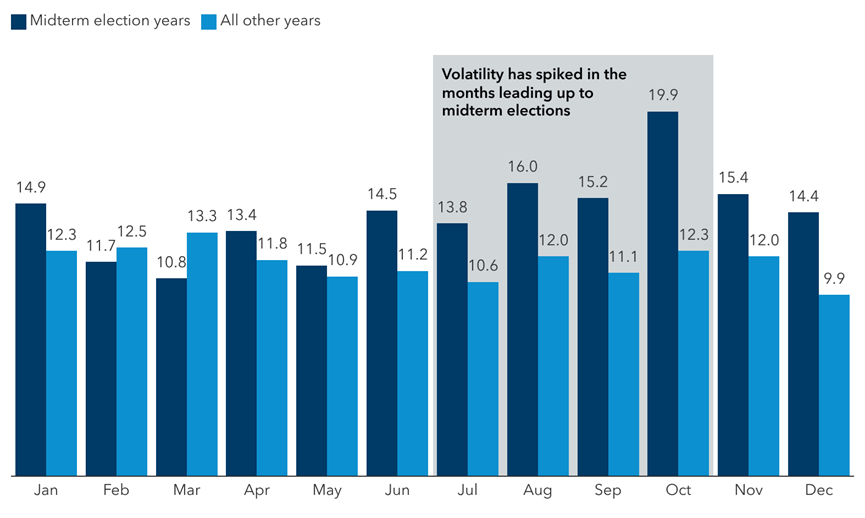

It may come as no surprise then that market volatility is higher in midterm years, especially in the weeks leading up to the election. Since 1970, midterm years have a median standard deviation of returns of nearly 16%, compared with 13% in all other years.

Figure 4: Midterm election years have come with higher volatility

Sources: Capital Group, RIMES, Standard & Poor's. Volatility is calculated using the standard deviation of daily returns for each individual month. The median volatility for each month is then displayed in the chart on an annualised basis. Standard deviation is a measure of how returns over time have varied from the average. As of 31 December 2025.

“I don’t think this election will be any different,” says Chris Buchbinder, an equity portfolio manager. “There may be bumps in the road, and investors should brace for short-term volatility, but I don’t expect the election results to be a huge driver of investment outcomes one way or the other.”

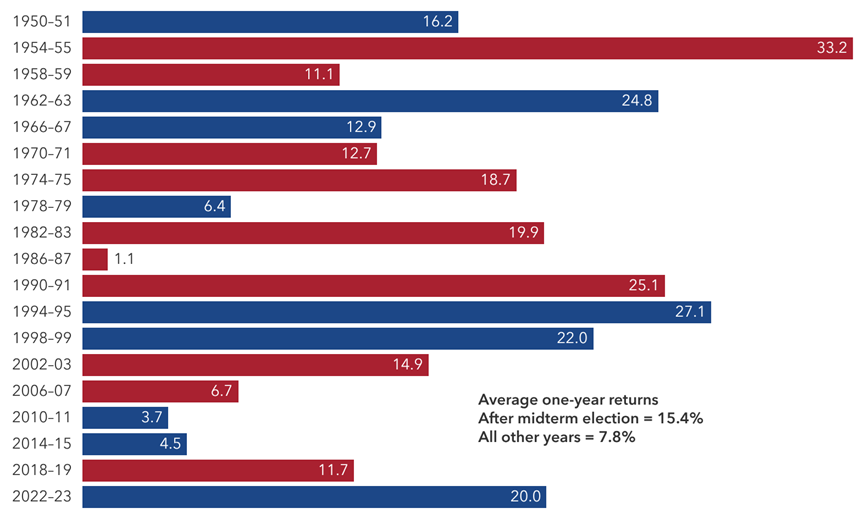

Post-midterm market returns have been strong

The silver lining for investors is that markets have tended to rebound strongly after Election Day. Above-average returns have been typical for the full year following an election cycle. Since 1950, the average one-year return following a midterm election was 15.4%. That is nearly twice the return of all other years during a similar period.

Figure 5: S&P 500 Index price return one year after midterm election

Past results are not a guarantee of future results.

Sources: Capital Group, RIMES, Standard & Poor's. Calculations use Election Day as the starting date in all election years and November 5th as a proxy for the starting date in other years. Only midterm election years are shown in the chart. As of 15 January 2026.

Every cycle is different though, and elections are just one of many factors influencing market returns. For example, investors will need to weigh the potential impacts of tariffs, inflation, and interest rates, as well as global economic growth and geopolitical conflicts.

The bottom line for investors

There is certainly nothing wrong with wanting your preferred candidate to win, but investors can run into trouble if they place too much importance on election results. That’s because, historically, elections have had little impact on long-term investment returns. Going back to 1933, markets have averaged double-digit returns during various government-control scenarios, including when a single party controlled the White House and both chambers of Congress, a split Congress, and when the president’s opposing party controls Congress.

Midterm elections — and politics as a whole — generate a lot of noise and uncertainty.

Even if elections spur higher volatility, there is no need to fear them. The reality is that long-term equity returns are driven by the earnings and perceived value of individual companies over time. Investors would be wise to look past the short-term highs and lows and maintain a long-term focus, regardless of which way the political winds may shift in any given year.

Matt Miller is a political economist, and Chris Buchbinder is an equity portfolio manager at Capital Group, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article contains general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. Please seek financial advice before acting on any investment as market circumstances can change.

For more articles and papers from Capital Group, click here.