Balance is something we aspire to in many parts of our lives, be it work and family time, diet or exercise. Likewise, as the past 20 years has shown us, a balanced approach to investing can help navigate turbulent market times.

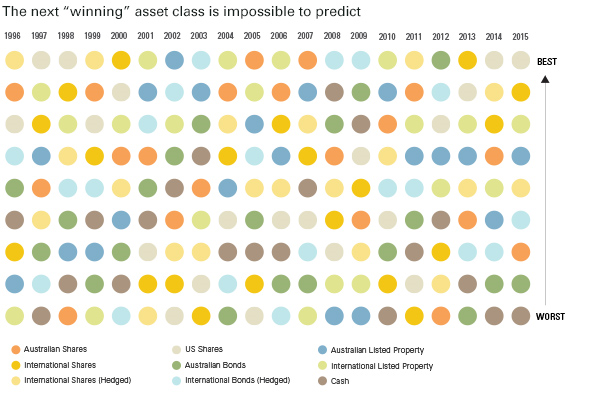

A strong body of research (including the 2013 Vanguard paper, The global case for strategic asset allocation) shows that the most important decision any investor makes is setting their asset allocation. However, it is almost impossible to pick which asset class will be next year’s winner, or in any subsequent year.

No discernible pattern of returns

When you plot the performance of all the major asset classes over the past 20 years, from domestic and international shares, domestic and international fixed income, domestic and global property and emerging markets, there is no discernible pattern.

It adds weight to the argument that past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns. Indeed, when you plot the various asset classes in different colours, it looks more like a random patchwork quilt than a tool for making investment decisions.

This is not to say investment markets have not rewarded investors over the past two decades. If an investor had placed $10,000 in a broad Australian share index fund 20 years ago, it would have grown to around $51,480 by 2016. However, investors in international and domestic shares have had to endure a wild ride. Think of the ‘tech wreck’ of 2000 and 2008’s GFC. By comparison, investors in fixed income or cash have had a much smoother journey but have also missed out on the higher returns from other asset classes. A conservative Australian fixed income portfolio would have grown more sedately to $37,606 over the last 20 years.

In the real world, investors have to decide where on the risk spectrum, with cash and fixed income at the conservative end and shares at the higher end, they want to sit. Another lesson of the past 20 years is that market shocks appear from unforeseen sources, such as the US residential housing market and its influence on the GFC.

Tolerance for risk in asset allocation

Investors need to clearly understand how much risk they can tolerate before deciding which assets to allocate money to. Setting an asset allocation is the first decision, but sticking to it is another thing entirely.

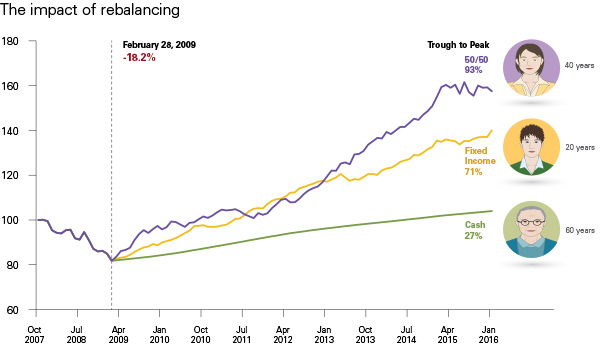

Let’s take the example of three investors who each had the same balanced portfolio (50% growth assets and 50% fixed income) back in 2007. After the GFC hit, by February 2009, their respective portfolios had all fallen 18% in value.

One investor decides it’s all too much and switches the make-up of their portfolio entirely to cash to stop the losses. The second investor is also worried about the dramatic decline in the portfolio’s value and opts to switch to a more defensive asset allocation, shifting the portfolio entirely into fixed income. The third investor, while concerned by the global market gyrations, decides to stick with the 50/50 asset allocation of their balanced fund.

Not surprisingly, these changes resulted in quite different portfolio performances. If we move forward from February 2009 to February 2016, the portfolio of the investor who shifted to cash grew by 27%, the fixed income approach grew by a healthy 71% (helped by declining interest rates), but the portfolio of the investor who changed nothing and stayed the course with a 50/50 asset allocation grew by a 93% from the trough of the GFC.

The asset allocation decision has been shown to drive about 90% of a portfolio's performance, but it is not a once-off static decision. The asset allocation for a 30-year-old, given their investment time horizon, may well be more aggressive with growth assets than a 60-year-old approaching retirement may feel comfortable with. And as the 30-year-old moves through different life stages the asset allocation should rebalance.

The biggest lesson from the past 20 years is that we should expect different asset classes to regularly change positions on the annual performance rankings. The investor’s quest is keeping the balance right between the various asset classes to give the best chance of reaching an investment goal.

Robin Bowerman is Principal, Market Strategy and Communications at Vanguard Australia. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.