If superannuation funds and other large investors decided to hold all their wealth in bank deposits, they wouldn’t need investment objectives. In practice, they want to achieve the best outcome to meet their needs. How do these investors choose between the myriad of investment alternatives such as different asset classes (e.g. equities versus fixed income), styles (e.g. value versus growth), structures (e.g. listed versus unlisted) and regions (e.g. Australia versus global)? By anchoring these choices in well-defined and articulated investment objectives.

How to set investment objectives

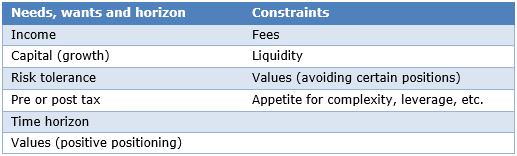

Setting investment objectives is not as simple as it seems. A menu of key considerations might look like this:

Values-based investing is a topical investment theme at present. Many large superannuation funds offer specific ‘Responsible Investing’ (or similarly named) investment options which allow members to express certain preferences regarding values such as exposure to fossil fuels, tobacco, gambling and cluster munitions. For some, values are a core, driving influence over how their capital is invested (a need or want); for others, it is an important second-order issue (a constraint).

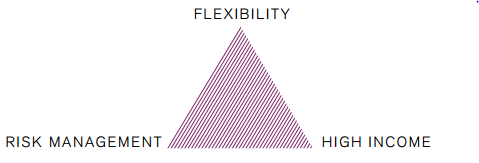

One key challenge with setting objectives is the competitive tension between the multiple needs and wants an investor may have. An example of this is the ‘Comprehensive Income Product for Retirement’ (CIPR) triangle of needs and wants of a retiree investor as recommended to the Federal Government last year in the Financial Systems Inquiry: Final Report:

Source: “Number One With A Bullet: Adding Defence to a ‘CIPR’ Retirement Solution for Super Members”, Parametric Research, December 2015.

Conflicting objectives and revealed preferences

Each of these investment objectives is much easier to deliver in isolation than in combination. For example, an options strategy providing downside protection can be bought by a superannuation fund as part of a CIPR portfolio to help protect a pension member from loss of capital, providing a ‘tick’ on risk management. However, pricing on such strategies is typically quite expensive and could erode much of the income generated, jeopardising the high-income objective. The exercise of investment objective-setting therefore needs to include not just a list of the things important to the investor but also some sense of the weight of importance of each of the objectives. This then becomes an optimisation problem for the fund or investor to solve; that is, to find the optimal combination of those aims with those weights as specified by the investor. Optimisation is a good way to solve problems like this also because it is relatively easy to add the investor’s constraints.

The other key challenge in setting investment objectives is the possibility of revealed preferences. An investor may say they care about one thing when, in fact, their behavior reveals something different. The onset of the GFC showed a clear example of this. Though most superannuation members articulated a long-term investment horizon in which short-term results would matter little, superannuation funds saw high levels of switching from growth options like equities into ‘safe’ options like cash. There is a challenge here for investors to examine their beliefs in the course of setting investment objectives. If I ask for a fossil-free portfolio, will I really be happy if my portfolio underperforms a market-cap index with no fossil fuel screens? If I ask my manager to beat the ASX 200 and the ASX 200 returns -4%, will I really be happy if my manager delivers -2%?

Max return v min risk

If institutional investors do just one thing as they set investment objectives, my recommendation is to use a distinction set out by JANA’s former Chair and Head of Investment Outcomes, Ken Marshman, in its January 2013 Capital Market Insights brief: determine whether the investor is a return maximiser for a given unit of risk or a risk minimiser for a given unit of return.

‘Max return for risk’ investors – typically including accumulating superannuation funds and other diversified portfolio investors – will craft investment objectives by defining a risk budget and then exploring what is possible in terms of returns and other outcomes. On the other hand, ‘min risk for return’ investors – typically including charities, defined benefit funds and many family offices – will more likely start with required capital and yield objectives and then look to mitigate the undesirable consequences of targeting these return objectives.

Raewyn Williams is Director of Research & After-Tax Solutions at Parametric, a US-based investment advisor. Parametric is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian Financial Services Licence under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) in respect of the provision of financial services to wholesale clients as defined in the Act and is regulated by the SEC under US laws, which may differ from Australian laws. This information is not intended for retail clients, as defined in the Act. Parametric is not a licensed tax agent or advisor in Australia and this does not represent tax advice. Additional information is available at www.parametricportfolio.com/au.