We all know that Australia is in the grips of a severe housing undersupply, with demand far outstripping the number of new homes being built.

Nationally, new dwelling approvals and completions have fallen sharply in recent years, despite a return to post-pandemic levels of population growth.

The result?

Higher prices, rising rents, and increased affordability challenges.

Government targets suggest Australia needs at least 240,000 new homes per year to meet demand. However, current build rates are falling well short, with recent annual completions hovering around 170,000 to 180,000.

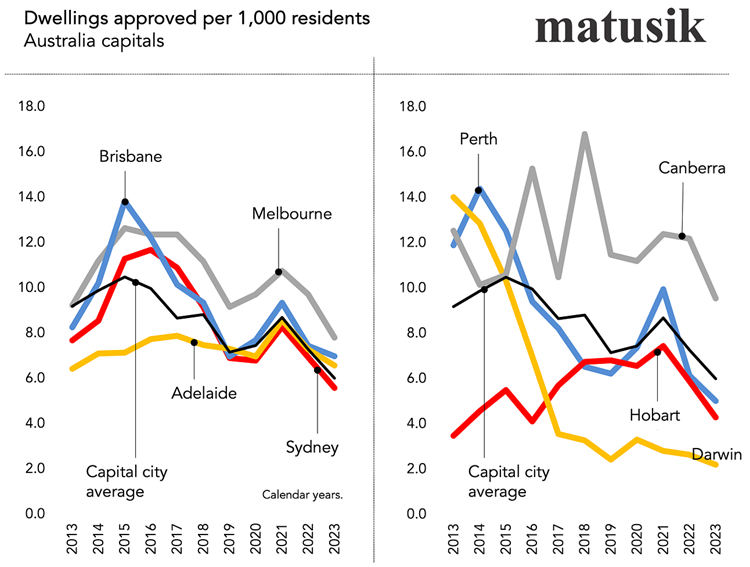

My chart shows that last year Australia approved just 6 new homes per 1,000 residents. This level of supply was 10 per 1,000 residents a decade ago. That’s a 40% decline!

When it comes to the capitals only Canberra and Melbourne are batting higher up the list, whilst Adelaide, Brisbane and Sydney are in the middle order and way off the pace are Hobart, Perth and especially Darwin.

Many want to blame this widening mismatch between new housing supply and demand on high immigration. This is only part of the issue. My chart shows that even in areas with middling population growth these laggards are struggling with new housing supply.

So what’s going on?

Several factors are stalling new housing supply.

Construction costs have soared, up 30 to 40% in some areas post-pandemic, making many projects financially unviable. Whilst built cost growth has slowed down, they are still rising and rarely fall. We are stuck with high build costs for a long time.

A shortage of skilled labour is said to be further delaying builds, while interest rate hikes have made it tougher for developers to secure financing. Yet I am not that convinced about labour shortages and that is a topic for a future Matusik Missive.

And last but least, planning and zoning restrictions in major cities and regions are also limiting supply, with approvals taking years to process. This for mine is the killer.

And housing undersupply is most evident in the rental market.

Vacancy rates in major cities are at record lows, often below 1%, pushing rents higher. Meanwhile, the cost of buying remains out of reach for many first-home buyers.

Addressing the issue requires faster approvals, better infrastructure planning, increased private sector investment, and support for alternative housing models like modular forms of construction and backyard homes.

Built-to-rent has a role but needs to spread beyond apartments and into the townhouse and small-lot home space. Most built-to-rent housing in American, for example, are detached homes, then townhouses followed by, a distant third, apartments.

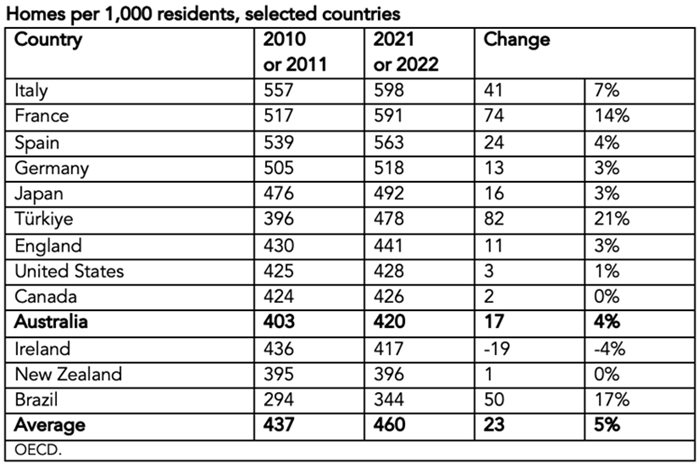

And when looking at the world stage, Australia is batting below many other countries when it comes to new housing supply. Those countries with limited new housing supply are facing (or have seen) a change in national government.

Source: OECD, Matusik Missive

Amazingly parts of Europe can build more new homes per head of population than we can. If Italy, France, Germany and Spain can build at rates some 25% higher Australia, surely we can do better.

But maybe we won’t. The same ‘head in the sand’ attitude applies to our energy needs down under.

Yet without action, affordability pressures will continue to mount, locking more Australians out of home ownership.

A word of warning. Millennials, Gen Z and some of the younger Gen X set will get even when their time comes. Watch these generations tax super funds in the future and other older generational financial windfalls when it comes to their time to rule.

Paying down the national debt will only be part of their reasoning. Getting even - i.e. being locked out of the housing market - will be a main reason for this revenge.

Michael Matusik is an Australian housing market specialist, providing commissioned housing and demographic market reviews, updates and outlooks for over 30 years, and shares his thoughts in his blog, Matusik Missive.