Albert Einstein is often quoted as having described compound interest as ‘the greatest mathematical discovery of all time,’ although this is probably apocryphal. One of the richest bankers in history, Baron Rothschild, described it as the Eighth Wonder of the World. The founder of Vanguard, Jack Bogle, said, ‘compound interest is a miracle.’

What’s all the fuss about? How many financial advisers discuss this incredible concept with their clients? In fact, an appreciation of compounding should be on every investment agenda.

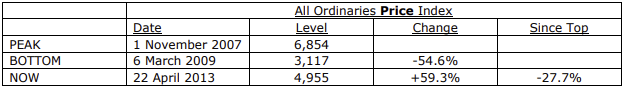

A good example of the problem of ignoring compounding comes from the most often quoted number in the Australian financial markets, the All Ordinaries Index. It’s mentioned in every news bulletin, and most of us know it’s currently about 5,000. Since it peaked at about 6,850 in November 2007, the market is down about 28%. Right?

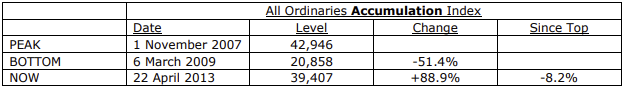

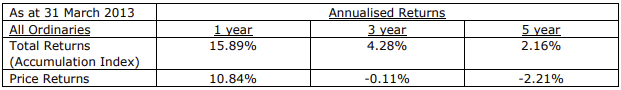

Investing in equities looks really bad compared with pre-GFC levels, but it’s ignoring the power of compounding. The All Ords is most often quoted as a price index, based on the prices of companies listed on the ASX. But it excludes the dividends they have paid, and so makes the performance of equities seem worse. The accumulation (or total return) index includes the receipt of and reinvestment of dividends. It is a better indication of the way the market has performed. The All Ords Accumulation Index is currently about 39,000, and it peaked around 43,000, so it’s down about 8%. Not wonderful but not 28% and not too terrible given the GFC was a one in 50 year event (hopefully).

If the Commonwealth Bank pays a fully franked $1.60 dividend and the day it trades ex-dividend, its share price falls $1.60, the All Ords will fall (if other stocks are unchanged). Does that mean an investor has lost money? Of course not. In fact, the dividend was fully franked and the investor is well ahead, it’s just that $1.60 is in their pocket, not the CBA share price. The accumulation index allows for this, as shown below.

(It could be argued that we should consider both the real price and the real accumulation index, that is, adjusted for inflation. In this case, the price index is currently down a very sad 37% from its peak, and even the accumulation index is down 20%, because inflation has risen 14.6% since December 2007).

Compounding should be part of everyone’s basic financial literacy, and a simple message without going into the mathematics is the Rule of 72. This formula provides an approximation of how long it takes to double an investment at a given interest rate. Dividing 72 by the rate of interest earned gives the number years it takes to double your money - the ‘doubling time.’

When the ASX300 Accumulation Index delivered returns greater than 20% in each of the pre-GFC years of 2004, 2005 and 2006, it created a climate of elevated investor expectations. Money flowed into equity funds, and cash and term deposits were boring and old-fashioned. Of course, the world has changed since then, and now commentators talk of the ‘New Normal.’ They tell investors to get used to low returns on both shares and bonds, with greater price volatility.

But it’s not really that bad. A return of 7% doubles an investor’s money in 10 years. In Australia, it is possible to achieve this return in the corporate bond market, or using some of the listed hybrids (ignoring tax). Or with some Australian banks paying fully-franked dividends of about 6%, then an investment can double in 12 years, even if the share price is unchanged.

The rule can be used in reverse, if an investor wants a certain amount of money in a defined number of years, then the required rate of return can be calculated. This may require the investor to take more risk than, say, term deposits and cash, and of course, this may leave the investment goal thwarted. It’s all very well to desire to double money in 6 years, but 12% per annum is difficult to achieve without accepting significant risk.

Perhaps one reason why compounding receives less profile than it should is that few people can imagine what exponential growth looks like. It’s easier to think about simple interest. Consider the difference between simple and compound interest by looking at the interest earnings in each of the 10 years of compounding at 7%. In the first year, the interest on $100,000 is $7,000. This is the same for both simple interest and compound interest. But then in the second year, compound interest is earned on $107,000, which is $7,490, an increase of $490. In the tenth year, the interest earned is $13,000, almost double the first year.

The value of compounding makes starting saving early even more important. For example, with a basic savings plan spanning 40 years (say from starting work at 20 until retiring at 60) of $1,000 a year, the earnings will be double that of doing the same over only 30 years. It doesn’t seem intuitively obvious but that’s the power of compounding. Similarly, a borrower who does not pay off credit card debt will find the compound interest expense will eventually outweigh the original debt.

In recent research by the Centre for the Study of Choice, UTS and the Centre for Pensions and Superannuation, UNSW, 1200 Australians were studied for numeric skills and financial competence. About 30% could not answer a simple question on compounding, yet we will soon be asking them to commit 12% of their gross salary to a concept that relies on it. The study centres are looking into improving the ways superannuation funds communicate with their members, and it’s not acceptable to simply state that super is too complex to understand. Most people have to deal with more complicated issues in their work and life.

And one more delightful fact: in every doubling period – say if interest earned is 7%, every 10 years – more interest is earned in the last decade than in all the decades that proceeded it. For example, taking a long term exposure of say 50 years (a reasonable assumption with a large proportion of the population living to be 90 or 100), more is earned after the 40th year than in the sum of the first 40 years. This also highlights the financial benefits of delaying retirement.

Of course, any analysis of compounding that forms part of a financial plan should make allowances for tax and inflation. An investor with $500,000 who decides he needs $1 million dollars to retire may take some comfort from achieving this goal by investing at 7% for 10 years. But $500,000 today will have the same purchasing power as $672,000 in 10 years even with inflation at only 3%.