There are key differences between investing in exchange-listed infrastructure securities versus unlisted infrastructure assets. These differences have important implications for investors and give rise to some commonly-held misconceptions.

The value of a typical infrastructure asset, or any long-dated asset, is determined by just two factors:

- The cashflow forecast to be generated by the asset.

- The risks associated with those cashflows actually materialising.

For an investor, the value of any asset is also impacted by the factors that stand between them and the cashflow generated by that asset. In relation to collective investment vehicles, there are three main factors:

- Leakage of cashflows to the asset’s controlling entity, e.g. fees paid to a fund manager.

- Reinvestment of the asset’s cashflows in the capital stock, e.g. for an airport, the use of asset cashflows to fund expansionary capital expenditure.

- The use of cashflows by the controlling entity to acquire other assets, e.g. a fund investing in unlisted infrastructure assets acquiring another asset.

A common misconception is that a listed infrastructure investment is more risky than an identical unlisted investment because of the inherent volatility in the former’s daily pricing. This view is both disingenuous and incorrect, as it confuses volatility in pricing with the volatility in cashflow. While some investors are attracted to the apparent comfort of a quarterly (or worse semi-annual) valuation of their unlisted assets, this ignores day-to-day developments.

Leaving aside the illusory benefit of not being subject to daily pricing, one would expect that a long-term investor might gain an advantage by investing in an unlisted infrastructure fund. In theory, the assets owned by such a fund should be cheaper than their listed equivalents as it is generally accepted that investors are prepared to pay a premium to have the ability to buy or sell an asset at any time. Indeed, it is somewhat counterintuitive to think that an inability to buy or sell an asset reduces the risks associated with it. Despite this, overwhelming evidence suggests that the imbalance between demand from funds looking to invest in unlisted infrastructure and supply of appropriate investment opportunities has led to the opposite being true.

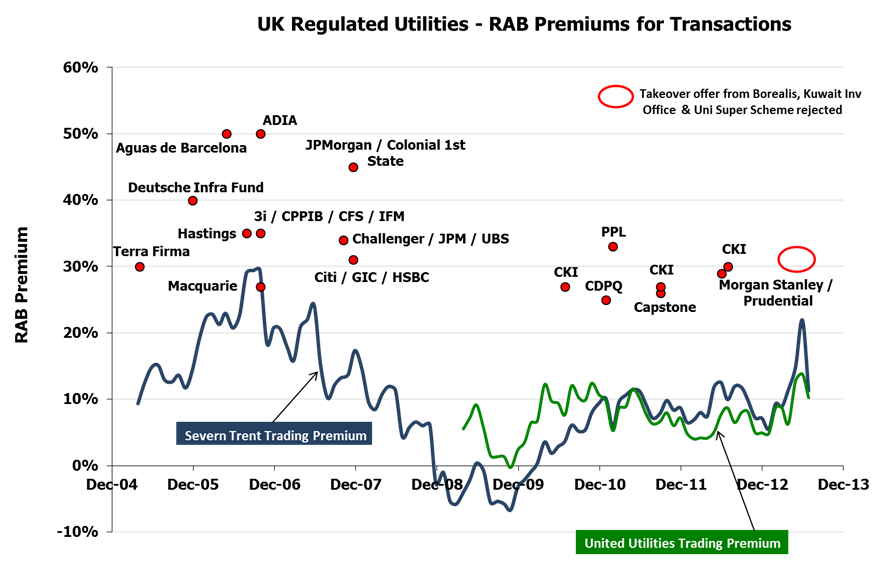

For instance, the following graph, showing the ratio of various entities’ Enterprise Values to their Regulated Asset Bases (RAB), which can be thought of as their net tangible assets, describes the history of utility acquisitions in the UK over the last decade. Each dot represents a deal done in the unlisted market, while the continuous lines show the equivalent trading multiples of the only two regulated utilities still trading at the end of the period in question:

Source: Magellan

Regulated assets in the UK are allowed to earn a return on their RAB. The regulatory regime in the UK is highly developed and utilities generally earn a small premium to the underlying cost of capital. Consequently, one would expect that the fair value of these utilities would be at a small premium to their RAB, which is indeed where we typically observe the listed assets to trade. However, the graph clearly shows a consistent pattern - unlisted asset transactions taking place at a 30% premium to underlying RAB. Note the rise and fall of Severn Trent’s share price in 2013, when news of a potential, but ultimately unforthcoming, takeover was made public.

The benefits of listed infrastructure funds

We believe that listed infrastructure assets benefit in comparison with unlisted assets:

- Listed infrastructure assets have been, and remain, cheaper than their unlisted equivalents.

- Fees charged by listed infrastructure funds are lower than those charged by unlisted infrastructure funds. Given that the infrastructure sector, when properly defined, should only provide modest, high single-digit returns over time, the difference in fees can be very meaningful.

- The listed market offers a significantly increased opportunity set.

- Daily liquidity allows investors to utilise more effective dynamic asset allocation, particularly in rapidly changing macroeconomic circumstances.

- Listed assets are able to provide greater diversity of asset exposures due to investment size limitations. This can be particularly important when a substantial proportion of an unlisted infrastructure fund is exposed to a single regulated asset (and is therefore heavily exposed to a potentially unfavourable regulatory decision at some time in the future).

- Regulated utilities, which make up the majority of the infrastructure investment universe, have little opportunity for the sort of value creation normally expected in private equity vehicles. This is because regulators generally do not allow such businesses to generate high levels of excess returns. As a result, it is favourable to achieve as cost-effective an exposure to the asset class as possible, i.e. through listed assets, as opposed to unlisted assets.

- Better transparency, given the strict conditions for disclosure imposed on listed entities.

There are, however, advantages in investing directly in unlisted infrastructure assets for certain institutional investors, i.e. owning positions in those assets directly on their books rather than through the medium of a fund managed by a third party. In particular, owning a large position in an asset directly reduces agency risk (the risk that the investor will not enjoy the full benefits of the asset’s cashflows). However, realistically speaking, only very large investment institutions with specialised internal infrastructure teams can expect to be successful when competing for such assets. Only a relatively small number of investment institutions globally would be adequately resourced for such an endeavour.

Conclusion

Appropriately diversified exposure to the infrastructure sector, when conservatively defined, should provide investors with a return of inflation plus 5-6% before fees. Such a return may be earned through exposure to either listed or unlisted infrastructure assets. However, the listed market offers investors superior post-fee return prospects, particularly given current and foreseeable market conditions.

Gerald Stack is Chairman of the Investment Committee and Head of Research at Magellan Financial Group and Portfolio Manager of the Magellan Infrastructure Fund. He has extensive experience in the management of listed and unlisted debt, equity and hybrid assets on a global basis. This material has been prepared by Magellan Asset Management Limited for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice. It does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs.