A friend was telling me about an old guy who used to live across the road from him. Known only as Mr Storm, he was 104 years old when he died recently. As a young man, Mr Storm had been a sugar broker in Indonesia, and came back to Australia after the Second World War with a decent amount saved. He managed his own portfolio, and as it grew substantially, he became a major supporter of many charities.

One day, the friend was chatting to Mr Storm on his front verandah, where he was soaking up the midday sun. As often happened, the conversation was interrupted by a phone call from the old man’s broker, and the friend heard BHP discussed. After the call, my friend said, “I saw BHP fell back 30 cents yesterday, to around $38. It’s lost a bit recently.” Mr Storm cleared his throat and barely lifted his head, the sun bright on his pale skin. “Most of mine cost me $6 in 1967,” he replied.

I tell this story because the perception of the market’s performance, whether it’s a good place to invest, depends on your investment horizon. Or more specifically, your entry point, because performance is usually determined by when you buy, especially for an investor rather than a trader. It’s amazing to recall that the Commonwealth Bank was floated in 1991 at $5.40, and 22 years later, not only is it now $68, but it paid a fully franked dividend of $3.61 last year. Should anyone who bought it in the float really care if the share price falls 10% or 20%?

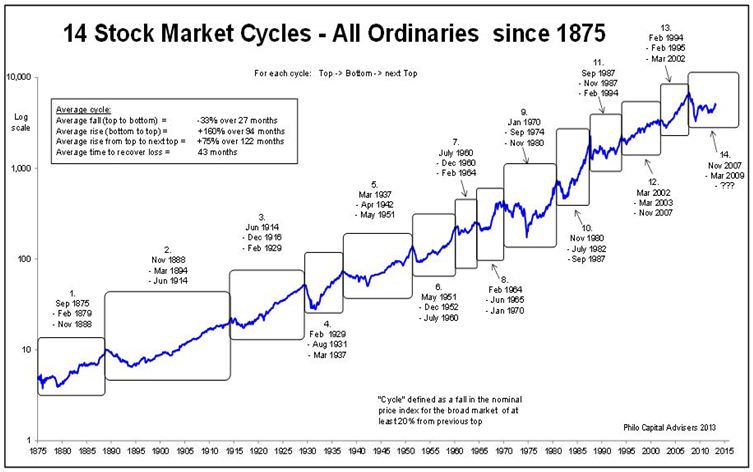

If you saw the graph below without knowing the time scale, you’d probably think the Australian All Ordinaries market was always a wonderful place to invest. Sure, there have been dips along the way, but in the overall scheme, it looks like a never-ending rise.

Then when you’re told the graph spans almost 140 years, a personal timeframe becomes more relevant. If it’s true, as the United Nations has said, that the first person to live to 150 is already alive, then that person should happily invest 100% of their retirement savings into equities, and it would probably be the best asset allocation possible.

Since 1875 there have been 14 stock market cycles in Australia, where a cycle is defined as a fall in the nominal price index for the broad market of at least 20% from the previous top. Please note there is a lot of detail in the following two graphs, and they are best viewed enlarged on your screen. The graphs require a number of assumptions relating to ‘old data’, as explained at the end of this article, and I am indebted to my close colleague, Ashley Owen of Philo Capital Advisers, for the graphs.

The interesting statistics from this graph are:

- the average fall from top to bottom is 33% over 27 months

- the average rise from bottom to top is 160% over 94 months

- the average time to recover the loss after a new bottom is 43 months.

For me, the 43 months is the most important number. Even after a fall of 20% or more, the market recovers to the previous high on average in less than four years. In a world where investors should expect to be retired for 30 years or more, we should have greater tolerance of short-term volatility.

This has crucial policy implications. Many of the MySuper funds being designed now as part of Stronger Super will adopt ‘lifecycle’ principles, with less allocated to equities over time. For example, Colonial First State will reduce the equity component from 90% at age 50 to 40% by age 60. Investors and advisers need to decide if that is too much too soon.

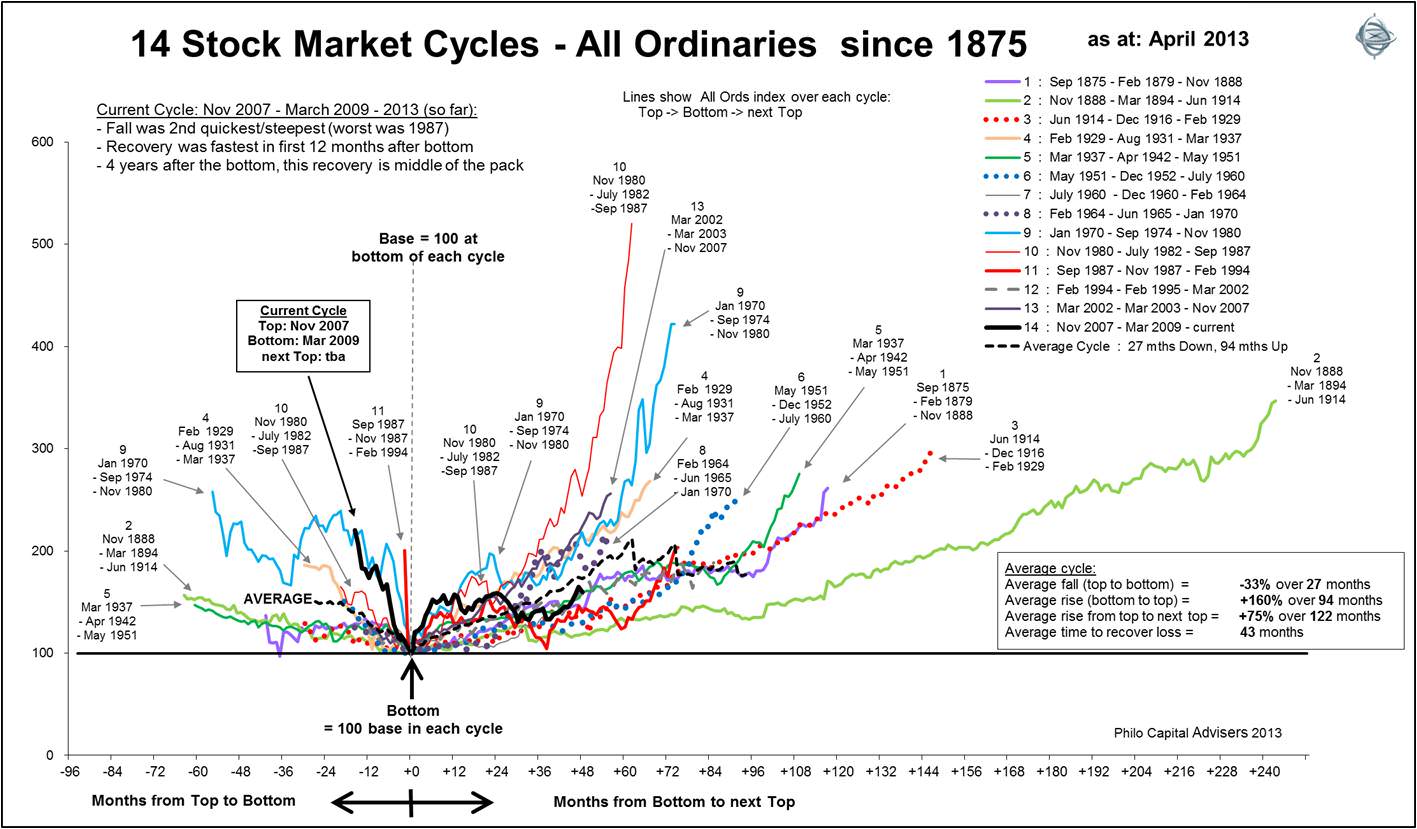

Of course, falls and recovery can be much worse than the average, and losing money just before retirement can be very stressful. The following chart shows a level of 100 at the bottom of each cycle, and the pattern of recovery from there. The variation is significant, which is one reason why comparing just one cycle to one other is problematic (again, best viewed enlarged on a screen).

The current cycle we are in (the solid black line in the graph), commencing from the high point of November 2007 to the low point of March 2009, was the second fastest fall on record, after 1987. If it felt like an extreme experience of wealth destruction, it was - even if you have been around as long as Mr Storm. But the recovery was the largest in the first 12 months after the bottom. Four years after the commencement of the recovery in March 2009, the current increase is in the middle of the pack compared to all the past cycles.

Cuffelinks is not in the business of forecasting markets, but if the average rise from bottom to top is 94 months, and we are about 50 months into the current one, then there’s little from history to suggest it should run out soon. But every period is unique and has its headwinds and tailwinds to contend with.

Mr Storm would probably ask why are you worried about a few years here and there, young man?

Some qualifications regarding old data:

- before 1979 the Sydney All Ords Index is used as a proxy for the ‘Australian’ index, but for most of the period Sydney was not the largest exchange by value or volume

- before 1936 the reconstructed ‘Aust All Ords Index’ uses the ‘Commercial & Industrial Index’ which didn’t include banks or miners, which were the largest stocks by market value and volumes

- before 1958, the sectors were equal weighted not market cap weighted

- before 1979 the index didn’t include speculative stocks – not even the large / heavily traded ones – eg Poseidon, Western Mining, MIM, Hamersley, Woodsreef, VAM, Harbourside Oil, etc.

- war-time controls on share prices and profits (1942-49).

The pre-1979 index data probably significantly over-estimates returns, and under-estimates swings. If it were a true market value weighted index of all (or even all major) stocks, it would probably be very different – higher booms and deeper crashes – particularly in:

- late 1880s silver mining boom, then 1890s collapse

- 1890s banking crash / depression

- 1929-31 crash

- 1939-42 collapse of gold miners

- 1968-70 mining boom then crash in 1970-71.