Viktor Shvets, Global Strategist at Macquarie Group, has a genius theory. It’s not genius for the theory itself but because he’ll be right whatever plays out in markets, and when job security in finance is as fragile as a soccer coach in the English Premier League, then that’s genius at play.

Here’s the theory. Shvets says business cycles are dead, and it’s due to three forces. First is excess capital. Financial assets have grown so much faster than the real economy that they are all that matter – it’s otherwise known as financialisation. He says the value of financial assets around the world is at least 5x greater than the real economy. It’s led to increasing inequality as those holding these assets have benefited, and those who haven’t have been left behind.

Second is government intervention in the economy and markets. Because an unwinding in financial assets would have devastating consequences for the global economy, governments and central banks are incentivised to keep the bubble going with fiscal and monetary stimulus. Yet, this serves to further entrench inequality.

Third is the pace of innovation. It’s created a winners take all economy and the winners will keep winning.

Due to the three forces, Shvets believes everything is a bubble and central banks and governments have every incentive to keep it inflated. That means traditional market measures such as mean reversion in earnings and valuation multiples as well as economic cycles are redundant.

Shvets tempers his views by suggesting that there are echoes of the 1930s in today’s world, and he hints that it may not end well - but we’re not there yet.

The genius of Shvets is that he’ll be right if markets continue to climb higher, and he’ll be right if they take an ugly turn.

While his theories aren’t especially original, especially on financialisation, and I disagree with business cycles being totally dead, Shvets packages his views nicely and they should keep him gainfully employed for some time!

Australia is the prototype for financialisation

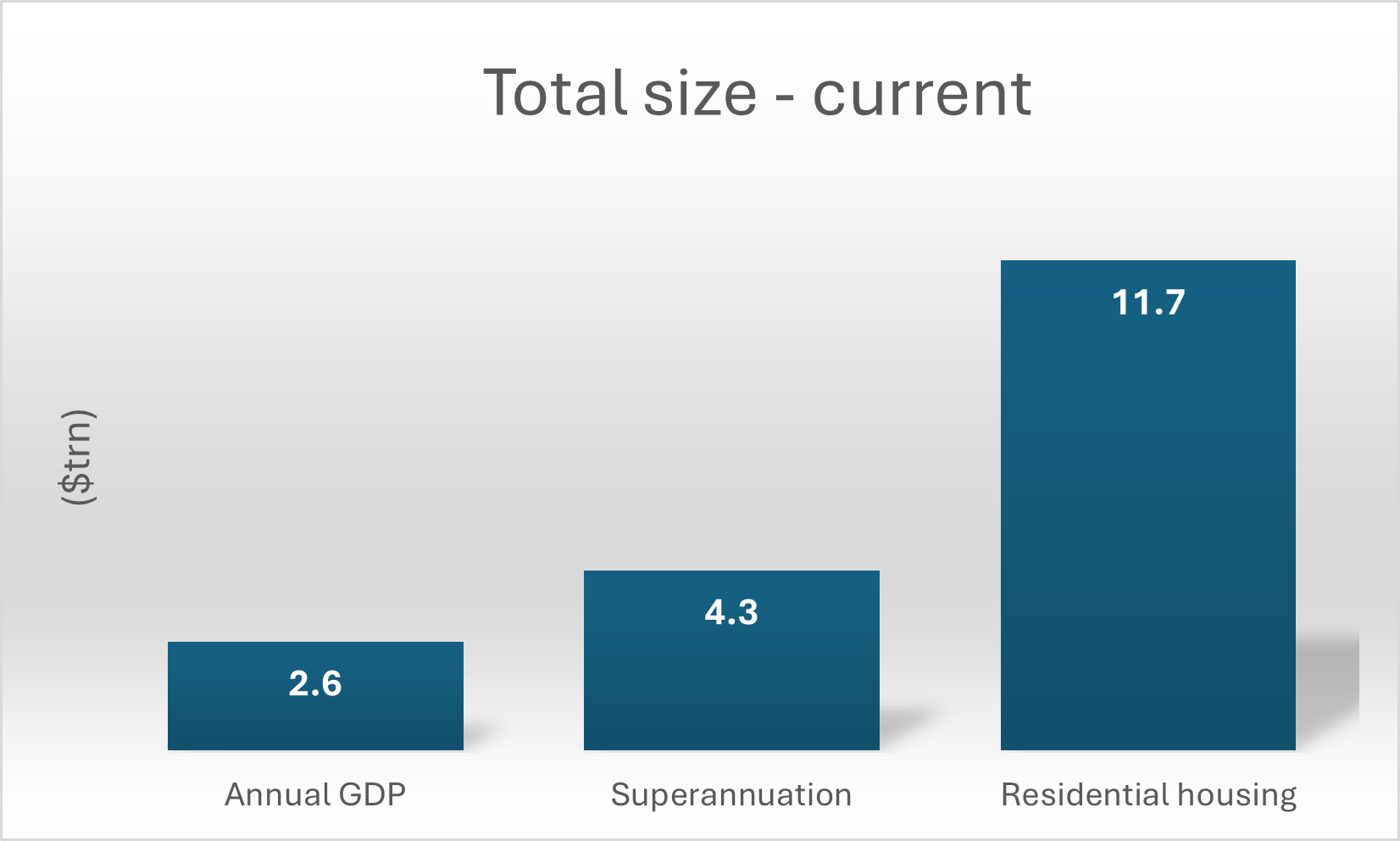

You don’t have to go far to see Shvets’ thinking on financialisation playing out. Look at Australia. Here, superannuation and housing dwarf every other asset class and the economy.

Residential housing is now worth $11.7 trillion, superannuation totals $4.3 trillion, while annual GDP amounts to just $2.6 trillion.

Source: Cotality, World Bank, Firstlinks.

In other words, housing is 4.5x larger than annual GDP, and housing and super combined is 6.2x the size of the economy.

That makes them too big to fail. Consider this: if super and housing fell in value by a combined 8%, which is not even a correction in market terms, that would equate to six months’ worth of GDP.

It’s no wonder everyone in Australia is obsessed with housing. And it’s no wonder why super is a giant in our stock market and broader financial industry.

Extrapolating current growth for super and housing

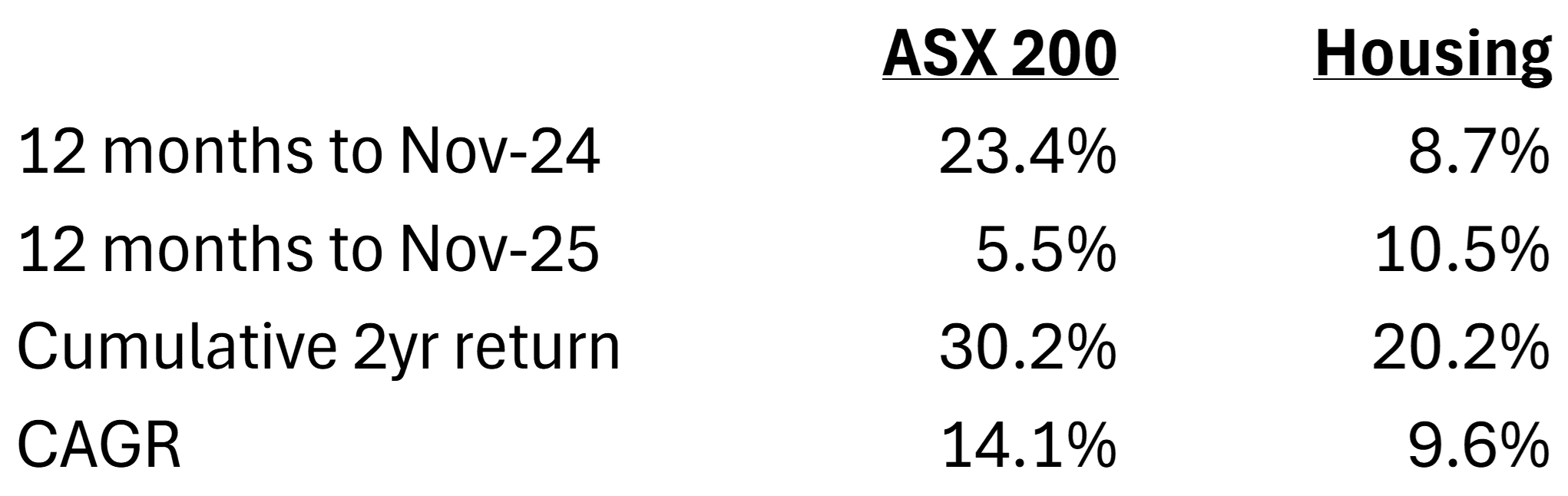

What happens if super and housing continue on their current growth trajectories? Is it sustainable, and if so, what are the implications for the economy and markets?

To gauge this, let’s do a simple experiment and explore what housing, super, and the economy could look like in 2050, just over 24 years away.

I’ll first assume that housing grows at 7% per annum until then. That’s slightly less than the 7.5% of the past decade, though it’s in line with a lot of people’s expectations that housing should double in price every decade.

With super, there are various consultant forecasts out to the 2040s, and from that I’ve got a good idea of what the size of the sector might be by 2050.

Finally, with GDP, Treasury’s long-term forecasts suggest economic growth of 2.25-2.75%. I’ve taken 2.25% because I think it’s most realistic. And I've also taken the mid-point of the RBA's inflation band of 2.5%, resulting in nominal GDP growth of 4.75% over the period.

With these assumptions, here’s what 2050 looks like:

Source: Firstlinks.

The residential real estate market would grow from $11.7 trillion to $63.5 trillion. The size of super assets would increase to $15 trillion. Meanwhile, annual GDP would jump to $8.3 trillion.

It’d mean housing would become almost 8x the size of annual GDP, up from 4.5x now. And housing and super would be 9.5x the size of the economy.

In this world in 2050, a 13% fall in house prices would equate to a year's worth of GDP.

If you think housing dominates dining table conversations now, wait until 2050!

And what about super? $15 trillion in assets would be an enormous amount of money to invest. Can they continue to outperform benchmarks like now? Consider that the world’s greatest investor, Warren Buffett, is struggling to invest the equivalent of A$539 billion today. Will it mean the super funds allocate more money to passive over active?

Think about what it could mean for the ASX. Super funds are already major shareholders in most large companies. What will happen when they are more than 3x the size of today?

What about the implications for the tax system? Super will surely be taxed more by then. And housing too. Especially if governments continue to lavishly spend other people’s money ie. the taxpayers.

Is it sustainable?

The question is: are my assumptions for future growth correct? That is, are current trends sustainable?

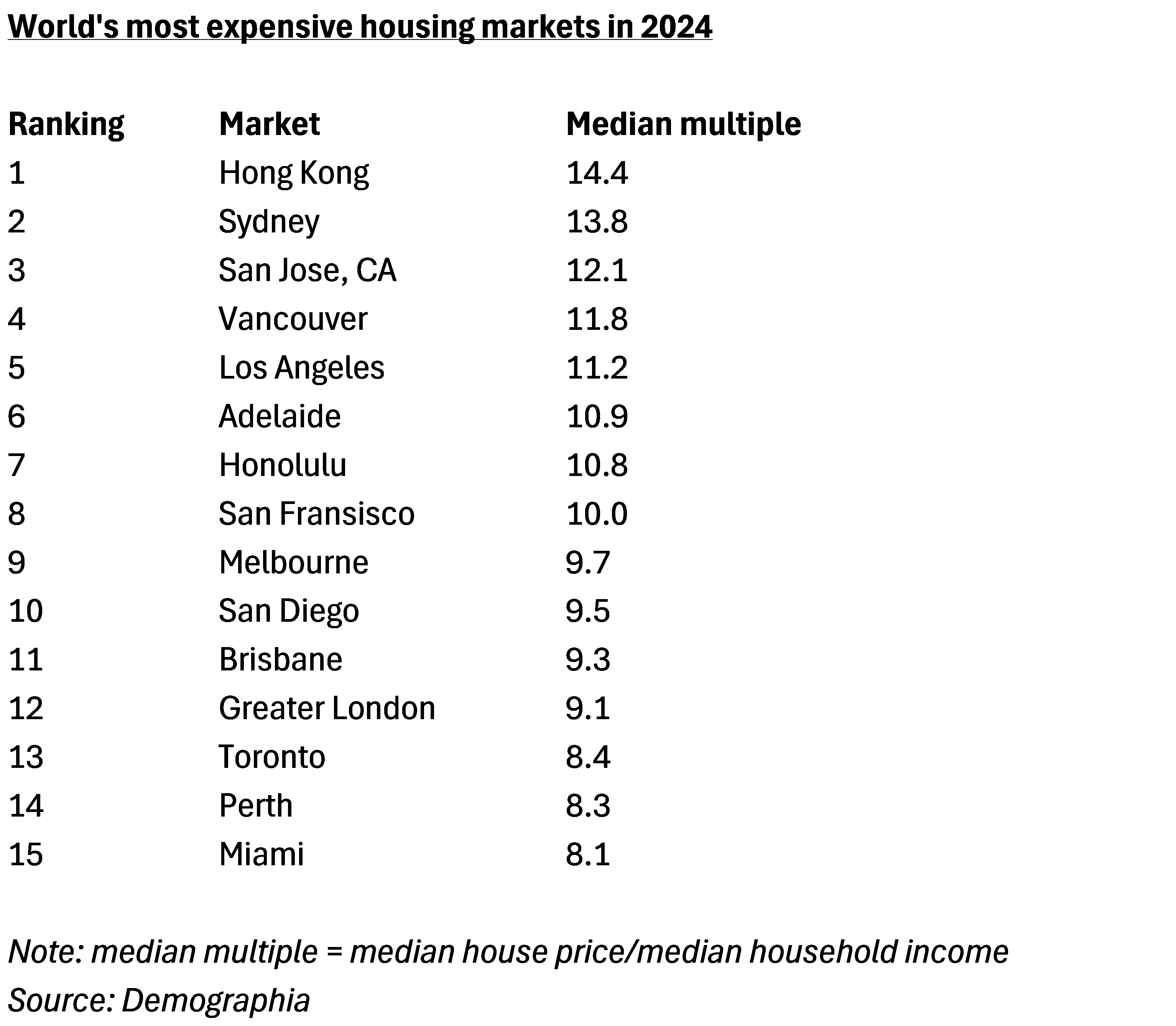

Let’s zoom in on housing. The current median house price is $920,000 across Australia. If prices grow at 7% per annum, the median price by 2050 would be $5 million. For the largest capital city, Sydney, a 7% growth rate would turn the current median house price of $1.52 million into $8.25 million.

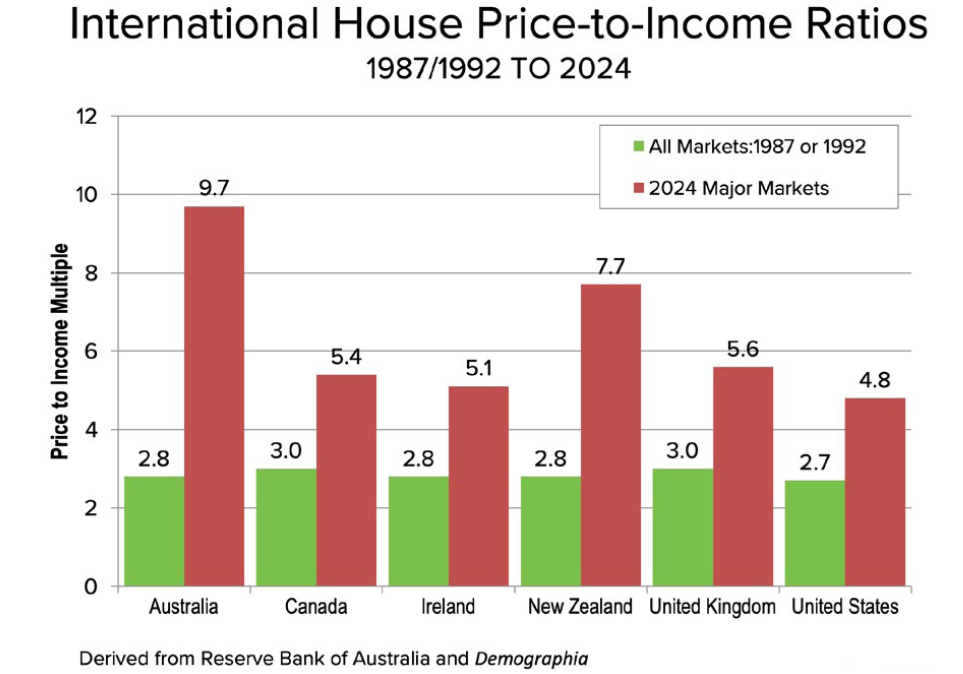

Is that realistic? A common measure of housing affordability is the median house price to annual household income ratio. Currently, that stands at roughly 10x – the median house of $920,000 versus median gross household income of $92,000. If I assume the current annual growth in wages of 3.4% persists to 2050, what happens to this ratio? The answer is that it would rise by the current 10x to 23.6x.

It should be no surprise that the ratio jumps that high given that I’ve assumed house prices grow at a rate of about double that of wages over the next 24 years or so.

According to Demographia, no country or city has ever had a ratio as high as 23.6x. Hong Kong got close in 2021 at 23.2x, but that was when interest rates were near 0% and the ratio there has since fallen to 14.4x.

As you might be able to tell, I’m sceptical that housing can grow anywhere near 7% per year over the long term. If prices continue to increase by more than wages, it will just make housing even more unaffordable than it is now.

If house prices were to grow by less than wages, it would mean that housing would shrink in importance versus the economy. It would mean less investment going into housing and more into other areas of the economy - potentially more innovative sectors. That could spur better productivity and growth.

Turning to super, there’s not a lot to stop it in coming decades. Yes, that might be a few market downturns, even bad ones, yet money will still flow in via the super guarantee.

While current debate on super centres on the switch from accumulation to decumulation, and the introduction of the $3 million super tax, attention in future is likely to turn to the size of the sector and what it means for performance. There isn’t nearly enough discussion on this, though I don’t think it’s far away.

*Note the original article contained an error calculating future growth rates for GDP in real rather than nominal terms. It has since been corrected.

Finally, I'd like to ask a favour of you. Firstlinks has been nomianted for a People’s Choice, Industry Media of the Year award at the Australian Financial Industry Awards. If our insights and reporting have helped your decision-making, please consider voting.

Cast your vote: https://ifpa.com.au/peoples-choice-australian-financial-industry-awards-2025/

James Gruber is Editor at Firstlinks.