In my 25 years in wealth management, the best conference I have ever attended was the FTSE World Investment Forum in May 2011. The main presenters were world leaders and academics from the investment management industry, and in this article, I will be drawing on the findings of two of them: Elroy Dimson of the London Business School and Roger Ibbotson, founder of Ibbotson Associates and Professor at Yale School of Management.

Let’s start with their conclusions. The market commonly measures the outperformance of active fund managers by the extent to which they beat an index, and refers to this as the alpha. The ability to produce alpha is generally attributed to the unique skill set of a fund manager. The presentations suggested this is not necessarily so. There are proven contributors to alpha which are persistent and systematic, and should not be attributed to manager skill, and hence are not alpha in the true sense of the word. These factors include:

- value

- dividend yield

- small companies

- momentum

- liquidity

In other words, the ‘alpha’ from these factors can be systematically extracted at low cost without any particular stock-picking skills from the fund manager, and in my observation of markets and fund managers, I agree with the merits of this argument. Let’s briefly examine each of these factors individually.

Value

Without becoming overly technical, a ‘value stock’ has a high ratio of its book value (that is, the net asset value of the company, calculated by total assets less intangibles and liabilities) to its sharemarket value. It is an indication whether a stock is under- or over-priced. A stock with a lower ratio is called a ‘growth stock’. In Australia, similar studies use low P/E ratios to define a value stock.

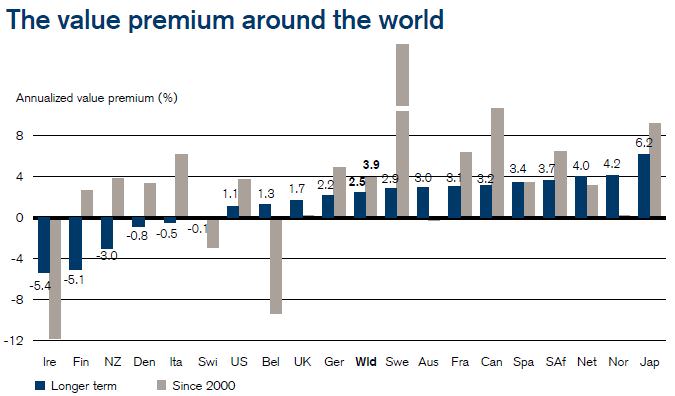

Dimson reported on his studies based on markets in 22 countries and regions from 1900 to 2011, and showed that in the US, value stocks beat growth stocks by 3.1% per annum, and in the UK by 5.8% per annum. These percentages produce extraordinary return differences over long periods, although it does not occur over all time horizons. For example, the long term outperformance for Australian value stocks is 3% per annum, but a small negative (that is, growth outperformed value) since 2000, as shown below.

Source: ‘111 Years of Stock Market Regularities’, Elroy Dimson, London Business School, May 2011.

Dividend yield

Again, Dimson found systemic outperformance for high dividend-paying stocks. In the USA, high-yielders beat low yielders by 1.9% per annum, in the UK by 2.7% per annum and in Australia by a healthy 5% per annum, although significantly less since 2000. Furthermore, when measured against the volatility of returns, high-yielders had lower risk and therefore delivered a better reward for risk.

Small companies

Dimson reported that small companies beat large companies on average around the world by 0.34% per month, and in Australia by 0.52% per month. Obviously, when the research combined size and value v growth, small-value is a major winner.

Momentum

It’s almost embarrassing for an investment professional to explain momentum. It appears that many investors buy shares or commodities simply because they have recently risen in price, and therefore have their own ‘momentum’. There are overlaps to behavioural theories such as ‘following the herd’ and ignoring one’s own better instincts. Dimson wrote, with colleagues from the London Business School, in a 2007 research paper,

Momentum, or the tendency for stock returns to trend in the same direction, is a major puzzle. In well functioning markets, it should not be possible to make money from the naïve strategy of simply buying winners and selling losers. Yet there is extensive evidence, across time and markets, that momentum profits have been large and pervasive.

Dimon’s research suggested past winners have beaten past losers for over 100 years, in the US by 7.7% per annum, and to a similar extent in Australia, although the returns come at a cost of higher turnover.

Liquidity

Roger Ibbotson argued that more liquid assets are priced at a premium, and less liquid are at a discount and therefore offer a higher return. He noted that liquid securities are easier to trade with lower market costs and are more desirable to high turnover investors, but as a result they are higher priced for the same expected cash flows. Thus, less liquid investments are better for longer term investors.

Ibbotson measured 3,500 US stocks from 1972-2010 and divided their liquidity (measured by daily trading volumes) in quartiles. The lowest quartile liquidity consistently outperformed. He applied the same reasoning to US equity funds and concluded that those with less liquid holdings also outperformed. He argued that as the liquidity (trading activity) of a stock rises, its valuation rises and investors pay too much for it.

His main message was do not pay for liquidity you do not need. Liquidity needs to be managed like any other risk, and changing stock liquidity creates return opportunities.

With trillions of dollars at stake in the investment management business, not to mention a few hundred thousand high-paying careers, these systemic advantages have been trawled over by analysts for decades. Some people devote their entire lives to one factor, and would probably be horrified by my one paragraph summary. In my mind’s eye, I can see a university academic with steam coming out of his ears as he waves around his 100-page thesis on momentum. Anyone is welcome to comment, and we will spend more time on each factor in other editions of Cuffelinks. My report on the conference is not an academic study of the literature, and no doubt an analyst can cut the data any way to produce other results.

The main conclusions I took from the presentations are that:

- there are highly-researched factors which have, over time, generated outperformance, although not over all time periods

- you should consider these factors when assessing whether an active fund manager really has any skill, or are they extracting a factor which should be more cheaply available

- there are some funds that do not need liquidity that may be able to extract a premium (for example, Listed Investment Companies traded on the market are closed-end and do not face redemptions, but do they extract a liquidity premium?).

Other presentations at the Investment Forum focussed on keeping costs low and risk diversification, emphasising the need to access these factors at competitive costs and across many sectors.