In the past week, some of the heaviest hitters in Australian economics have addressed the impact of various policy changes on the budget deficit. Professor Ross Garnaut, former Governor of the Reserve Bank, Bernie Fraser, and former Secretary of the Treasury, Dr Ken Henry, have all spoken publicly. Ken Henry said the entire welfare system needs to be fixed, and “There will be a day of reckoning”, specifically identifying the age pension as needing attention. And Treasurer Joe Hockey is currently worrying about where the money is coming from while he frames his first budget.

I have previously suggested that reform of the age pension is likely (Cuffelinks, 21 February 2014). Age pension reform is a complex, controversial and sensitive issue. What may seem at first glance an obvious (and perhaps an easier) reform opportunity proves difficult once all issues are considered. The indexation of age pension payments is a case in point.

Background on age pension payments

Currently the full age pension fortnightly base payment for a single is $751.70, which can increase to $827.10 once supplement payments are included. Combined couple base payments are $1,133.20 ($1,246.80 with supplements).

Base pensions are indexed twice a year. The pension is increased to reflect growth in the Consumer Price Index and the Pensioner and Beneficiary Living Cost Index, whichever is higher. When wages grow more quickly than prices, the pension is increased to the wages benchmark. The wages benchmark sets the single base pension rate at a minimum of 27.8% of Male Total Average Weekly Earnings (41.8% for the combined couple rate).

Wages have grown at a faster rate than inflation, by about 1.2% pa over the last 30 years. It is likely that real wage growth will be positive and thus it will be changes in wages which drives changes to base pension rates.

Wage indexation is generous, but is it sustainable?

The Department of Social Security website states that the “Age Pension is designed to provide income support to older Australians who need it, while encouraging pensioners to maximise their overall incomes.” If income support is interpreted to mean poverty alleviation then wage indexation may appear a generous provision by the government. An argument could be made that poverty alleviation refers to a cost of living and this makes inflation a more relevant indexation reference.

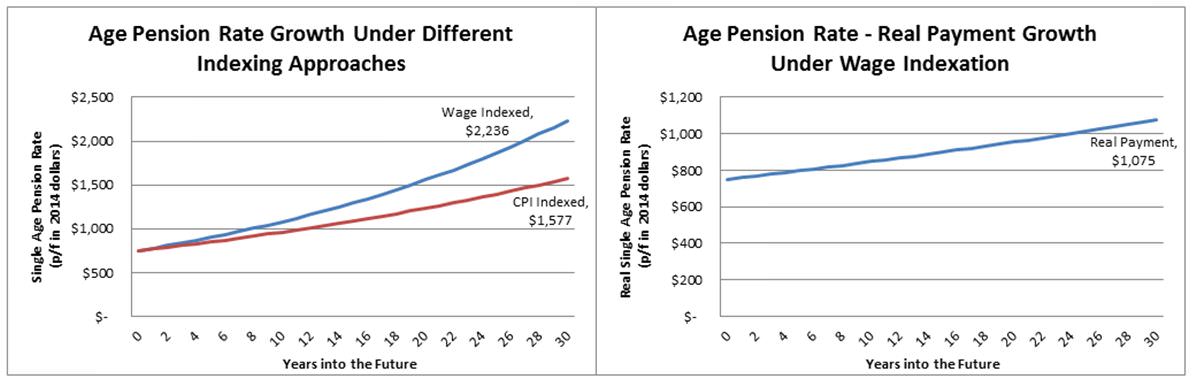

Given 40% of the population are predicted to receive the full age pension at some point in their lives and 80% of the population receive the part age pension, then wage indexation will have a significant impact on the retirement outcomes of the majority of Australians. Consider the chart below where we assume that real wage growth is 1.2% pa and inflation is 2.5% pa into the future.

Chart 1: LHS: Single age pension rate growth under two indexing approaches; RHS: Real single age pension rate under wage indexation.

While, as expected, age pension payments grow faster when indexed to wage growth rather than inflation, it has a remarkable impact over time. In today’s dollars, in 30 years’ time, age pension payments would be 43% higher ($1,075 per fortnight).

What does this mean for retirees? For those on the full aged pension, real aged pension payments will be significantly larger when they are indexed by wage growth. The story for those with higher super accumulation balances is less clear as the threshold income levels also rise with wages making the age pension harder to access.

If age pension recipients are far better off under a wage indexation process then this means the government is paying out more. If we take Treasury’s forecasts (from the Intergenerational Report), age pensions will cost 3.9% of GDP in 2050 or about $60 billion in today’s terms. If we just look at those on the full age pension (which I will guess makes up 75% of the budget expense) then an estimate of the difference in age pension expenditure in 2050 due to the choice of indexation is $18 billion ($60 billion x 75% x 40%). From now until 2050, an estimate of aggregate government expenditure due to the choice of indexation method is $270 billion. That’s a large number in anyone’s books!

This is not forecast to create a huge windfall benefit for retirees (as we saw in Cuffelinks on 7 February 2014, the benefits of higher wage growth are modest for low income earners). This is because the increased age pension payments may be offset by income tax due to bracket creep. Over time tax brackets have tended to be indexed by inflation rather than wage growth and this means more people, including future full age pension recipients may actually pay income tax (this in itself is an interesting policy issue). So what the government giveth with one hand, it may taketh with the other.

The social importance of wage indexation

The Harmer Review advocates wage indexation, or ‘benchmarking’, of the age pension rate. The finding of the Harmer Pension Review was:

“The Review finds that automatic indexation of pensions and a two-part approach of benchmarking and indexation should continue. Benchmarking pensions relative to community standards should be the primary indexation factor, with indexation for changes in prices acting as a safety net over periods where price change would otherwise reduce the real value of the pension.”

The primary argument is that benchmarking maintains the relativity of the age pension to community measures of living standards, and avoids dispersion of quality of life increases between those who are working and those who are retired. Changing living standards and changing social and technological structures in society are important issues for which income is a better proxy than inflation. The example provided in the Harmer Review was computing and the internet. Most would find that computer and internet access is a near essential part of life now.

The Harmer Review is well-balanced and raises additional concerns about wage indexation:

- In an aging society where the ratio of pensioners to workers is increasing, an age pension rate indexed to wage growth will mean that workers, via tax, will forgo an increasing proportion of their income. This would create an inequity in the other direction – pensioners maintain living standards while workers experience declining living standards (due to higher income taxes). There are obvious social and equity issues that follow from this. Any sustainability-driven approach to link pension payments to tax receipts would likely find wage indexation unsustainable.

- Wage indexation provides a mechanism to share the benefits of productivity gains across the community. There are other claims on productivity gains, notably those that come from the workers themselves (working harder and smarter), their employers, and ultimately their shareholders if the employer is a corporate. Governments may argue for their piece of any productivity improvements as well.

Some countries have moved away from earnings to price-based indexation, arguing that the purchasing power of pensions is preserved but that fiscal constraints restrict them from providing wage indexation. Of course they could in the future provide one-off adjustments to the pension rate to improve social balance if the fiscal position permits. One positive aspect of indexation is that it is automatic and removes uncertainty and politics from pension rate determination.

Indexation of the age pension rate is a complex, controversial and sensitive area. The debate needs to balance both economic and social issues. Ultimately, given the numbers are so large (circa $300 billion over the next 30 years), I’m sure the government at some point will review indexation practices as part of its desire to bring the burgeoning budget under control.

David Bell’s independent advisory business is St Davids Rd Advisory. In July 2014, David will cease consulting and become the Chief Investment Officer at AUSCOAL Super. He is also working towards a PhD at University of NSW.