Behavioural economics has revealed the vast gulf between what people say they want and how they behave. It makes life challenging for financial planners, superannuation funds and financial institutions attempting to deliver the right products and services.

However, new approaches built on data, analysis and algorithms can help solve the paradox of advising people who are effectively strangers to themselves.

The difference between stated and revealed preferences

Financial planning questionnaires typically ask clients for stated preferences such as how they believe they will react in different circumstances, but decision theory and behavioural economics explain why people’s actions regularly deviate from their intentions.

For example, the second-highest financial priority cited by seniors in a recent ASIC survey was "having enough money to enjoy life and do what they want to do" (69%). Yet a significant proportion of retirees spend less than the age pension according to the Milliman Retirement Expectations and Spending Profiles (Retirement ESP).

Meanwhile, the industry has long known that the stated preference for reliable retirement income doesn’t translate into sales of products such as annuities.

These inconsistencies suggest retirees are prone to stronger opposing forces that change their behaviour in ways they don’t realise. It makes setting personal goals a complex task because people don’t know themselves, let alone how to balance competing desires.

Comprehensive data helps. The Retirement ESP has revealed several surprises about the behaviour of retirees which differs from industry assumptions.

Shachar Kariv, Professor of Economics at UCBerkeley, recently pointed to gamification, or the process of melding game-like actions with everyday tasks, as a more accurate methodology than questionnaires. It can show how clients will actually behave (their revealed preferences) rather than how they think they will behave (their stated preferences).

“People will enjoy it because it will be a game,” Kariv said at a recent Milliman breakfast event. “It’s going to be fun and fast. You can do it from your phone or tablet and in different periods of time.”

For example, a coin flipping gambling game can reveal players’ risk-return trade-offs and preferences in a mathematically-sound approach. Various studies are now showing, with statistical certainty, just how certain segments of the population behave by using these techniques.

The problem with risk

Understanding the risk that hides behind investment returns is complex.

Individuals may think of risk in terms of the possibility of investment losses or in terms of not achieving their financial goals. The asset management industry on the other hand typically defines risk in terms of the distribution of returns (volatility). This disconnect between everyday Australians and investment professionals can lead to poor outcomes.

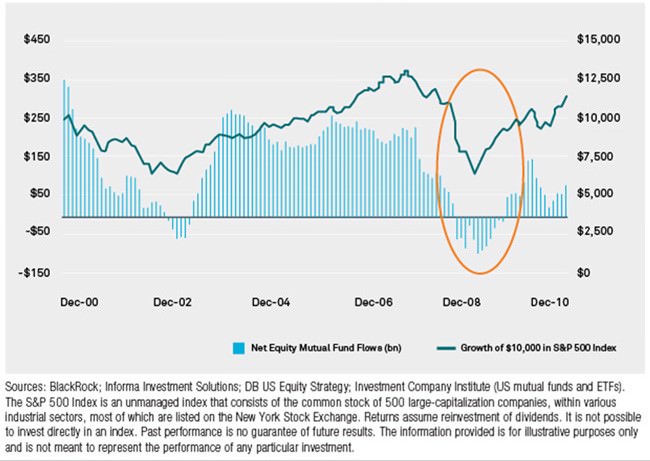

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that individuals make poor predictions (stated preferences) about their level of risk tolerance. Many investors withdraw or switch their portfolios to cash when equity markets decline. The following chart is now dated but fund managers confirm similar patterns of flows recently where performance varies against a benchmark.

S&P 500 Index performance vs. 12-month equity mutual fund flows

A secondary issue is the way the industry gauges investors’ risk tolerance with standard risk and return questionnaires. As Kariv, who is also Chief Risk Scientist at risk profiling firm Capital Preferences, said:

“I would claim there is no scientific basis whatsoever for this method. A survey is like designing a bridge without writing any mathematical equations. You will not drive on a bridge that the engineer has designed without writing any mathematical equations.”

Accurately measuring risk capacity, not just risk tolerance, is essential if investors want to achieve their goals. Risk capacity is the level of risk an investor can withstand while still meeting their objectives with a reasonable level of certainty.

For example, many older investors have higher levels of loss aversion, which leads to lower risk tolerance levels. However, wealthier investors with high levels of cash to fund their day-to-day lifestyle can have higher levels of risk capacity.

Risk capacity is also relevant for younger investors. The ASX Australian Investor Study 2017, which surveyed 4,000 Australian residents, suggests that young investors may be more risk averse than previously thought. It found that 81% of investors aged under 35 were seeking guaranteed or stable investment returns.

However, young investors have a higher risk capacity when it comes to their retirement savings, given that they will have decades in the workforce and can withstand market gyrations.

Analysis can discern the difference between risk preferences and risk capacity and help advisers balance the tension to find a solution that works for their clients.

Most people do not know their spending or lifestyle habits

People are bad at estimating how much they spend, which makes it difficult to choose the optimal investment strategy to lift retirees’ standards of living.

The evidence is the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) data, which surveys more than 9,500 households. It provides information and insight into everyday Australians. However, spending surveys of this nature have shortcomings when applied to the context of financial planning.

For example, an industry analysis estimated that the median expenditure for households aged 65-69 was $24,640 a year while the average was $33,944. The Retirement ESP, which uses bank transaction data from more than 300,000 retirees, shows that the median couple aged 65-69 spends $34,858 while the average expenditure was $43,675. This is a significant difference even when accounting for the different time periods of the underlying data (2015 versus 2017).

Other differences are also revealed when people qualitatively assess their own lifestyle compared to a quantitative assessment of data. For example, 2,527 people surveyed in the 2015 HILDA survey said they smoke at least one cigarette a week. However, 38% of these respondents reported spending no money each week on cigarettes.

These discrepancies in spending survey data are not material when taken in the appropriate context. However, they do highlight the potential risks of relying on spending survey data to form views about the spending needs of future retirees.

Financial advisers, and increasingly, super funds, develop an understanding of clients’ and members’ qualitative information and life experiences because they spend time with them. However, a mix of tools powered by data, analysis, and algorithms can help them bridge the gap between the things people say they want and how they actually behave.

This type of quantitative information is a key component of this approach and can provide a clearer view of retirement expectations and what people need to do to achieve their goals.

Jeff Gebler is a Senior Consultant at actuarial firm, Milliman. Read more about the Milliman Retirement ESP here.