Recent mandatory asset disclosures by politicians suggest a widening wealth divide between our elected representatives and those they represent. Those disclosures show that our politicians aggressively invest in the property asset class and much more so than the average Australian.

With a raging debate concerning the unaffordability of housing, disclosures of property investments by sitting members suggest that conflicts of interest may exist in the Houses of the 48th Parliament. Importantly, those conflicts of interest are inferred but not openly disclosed, either prior to or during parliamentary debates concerning housing policy.

A comparison of the ratios of investment in property – politician to average household – makes for some alarming observations.

Let us start with the Australian household sector – the taxpayers and the voters.

ABS data reveals there are 10.7 million households. There are 27.2 million Australians and thus the average household has about 2.5 people in residence. This ratio includes the 2.9 million households where people are living alone.

In 2023, there were 2.2 million property investors representing 19% of all ‘individual taxpayers’ that the ATO noted as having an interest in property. The majority of this cohort – about 1.5 million – had an interest in just one investment property. 450,000 had two properties and about 200,000 had three or more properties (representing less than 2% of individual taxpayers).

In passing it is interesting to note that about 10 million individual taxpayers (who were not in business) lodge tax returns, whilst there are about 15 million people employed. A third of workers do not lodge a tax return. However, property investors invariably lodge tax returns as they claim a range of deductions against appropriately disclosed rental income.

Australia’s 2021 census disclosed that 3.3 million households rented, about 31% of households. This includes renters from the government sector (about 277,000 renters).

What are the comparative numbers for our politicians?

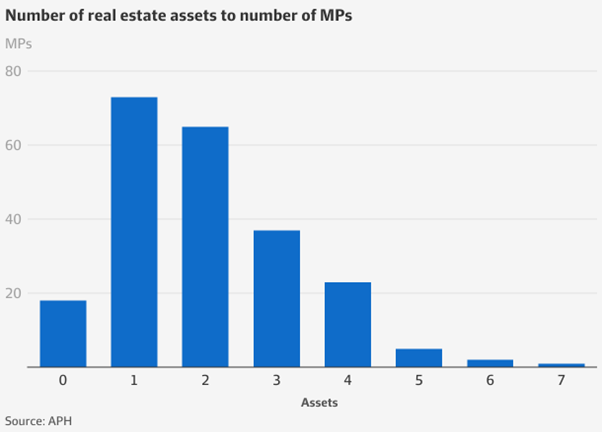

The following chart, reported in the Australian Financial Review, covers the real estate assets of the 226 members in the Commonwealth Parliament (in the Houses of Representatives and the Senate).

In reviewing the asset and investment registers of politicians the following are my observations.

First, there are ‘apparently’ 12 politicians who declare that they do not own a residence. That is 5% of the political cohort, therefore 95% of politicians reside in a house that they own, with or without a mortgage. It is not immediately clear as to whether the 5% of renters may have an investment property – directly or indirectly.

The chart above indicates that:

- 18 members have no property investment (8%) – if they rent then this compares to the 31% of Australian households that rent.

- 72 members have one property (32%) – just their residence.

- 65 members also have one investment property (29%).

- 37 members have two investment properties (17%).

- 23 members have three investment properties (10%).

- 8 members have four or more investment properties (3%)

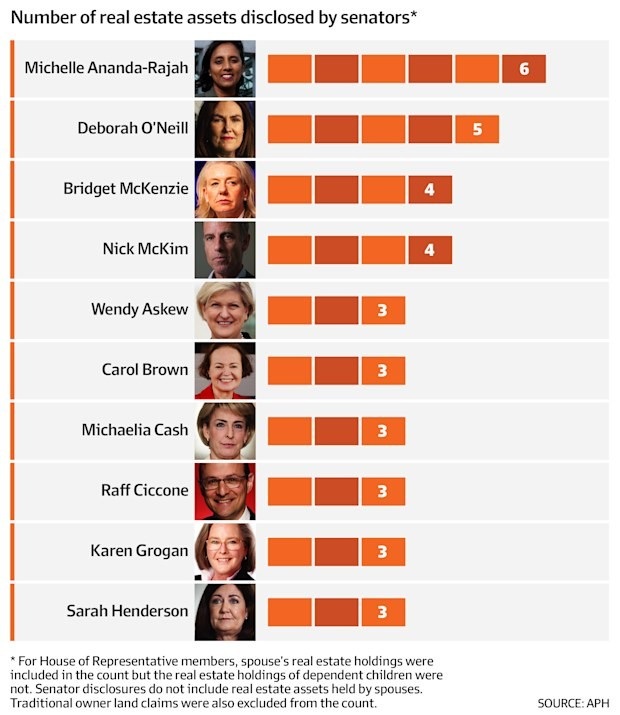

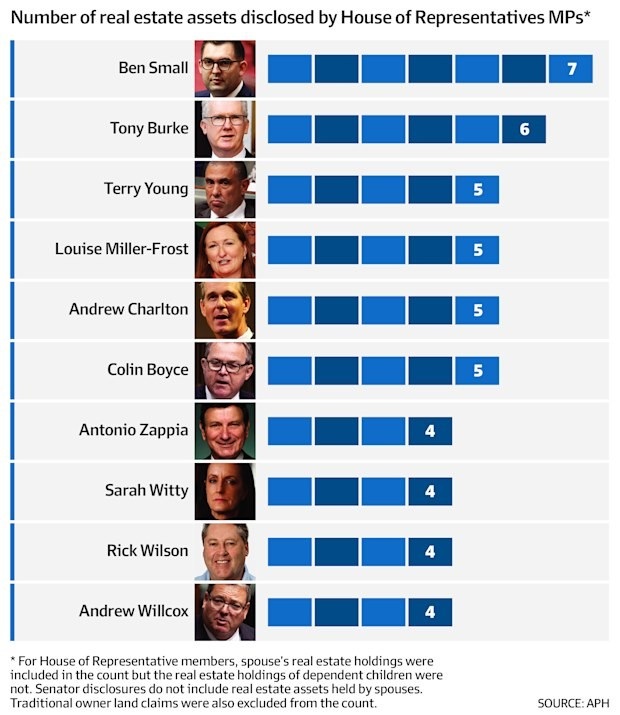

Thus, most politicians, some 60%, own one or more investment properties. The AFR produced the following tables to highlight our Parliament’s significant investment property owners.

Readers should note that different disclosure rules apply to Senators (not required to include related parties) to those that relate to Representatives.

In any case, given that our politicians are compelled to disclose the assets of their household, the following comparisons (politicians to the voters) are deduced:

- 60% of politician’s households have an investment property compared to only 20% of the total for Australian households; and

- 30% of politicians have an interest in more than one investment property compared to just 3.5% of Australian households.

The differences are stark - Politicians have multiples of investment property assets compared to average Australians.

Conflicts of interest are stark

It is remarkable that our politicians, as a cohort or subsection of society, have such a significant investment slant to investment property. Are there other factors at play?

It is well understood, and it is a strategic investment strategy, that property investment normally requires leverage. Multiple property investments absolutely require leverage to access negative gearing taxation benefits. Politicians access property investment loans at a greater rate than the broader population. Why?

Is it a reflection of unfair influence? Does it suggest that a politician’s income generating capacity, to support loans, is better or more certain than average households? Do politicians have job certainty?

In Question Time, is there so much conflict across the chambers that it is to no party’s benefit to highlight them?

So much for the workings of democracy!

This raises the issue of conflict of interest - between those who govern, debate and then determine the laws that relate to property investment - with those they represent.

The determination of negative gearing tax rules relating to property investment, and the oversight of leverage provided by the regulated financial institutions, requires a balanced policy debate. Can that occur in a Parliament that is weighted towards people who actively use property as an investment activity when most of the population either do not or cannot?

The broad asset disclosure declarations of politicians should not be accepted as the basis of dealing with conflicts of interest. In business, good corporate governance requires a conflicted beneficiary to make both a full disclosure and to absent themselves from a vote.

However, the ability of politicians to generate wealth should not be curtailed by public service. Remuneration and incentives should be met by more sensible salary and entitlements – so long as they are transparent and based on the generation of a measurable and better standard of living for the population they represent.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.