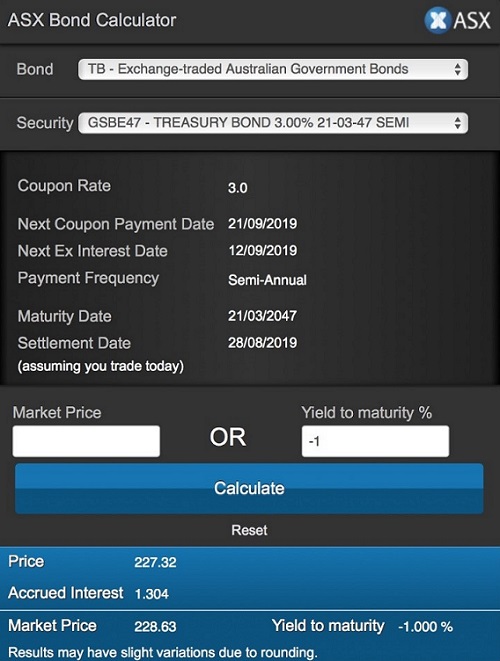

It seems someone at the ASX must have read Graham Hand’s introduction to Firstlinks Edition 320, about the ASX bond price calculator not being able to handle a negative yield. Because now it can.

We see that for the 3% coupon bond maturing in March 2047, that a minus 1% yield equates to a bond price of $227.32. But does that seem reasonable?

How to understand this new world

Compare that to a price of $148.08 for a yield of 1%. And at a 0% yield, the price will simply be the sum of the future coupons plus the face value of $100 at settlement, being $182.50. Therefore, a price of $227.32 for a minus 1% yield would appear to pass the sensibility test (which can also be verified in a simple spreadsheet).

Negative-yielding debt is globally prevalent, but particularly in Europe, with Germany recently selling over 800 million euros worth of 30-year bonds yielding an average minus 0.11%. Investors are paying the government to hold their debt. For 30 years!

This phenomenon is foreign to many investors, and they are finding it hard to come to grips with what a negative yielding investment actually means. So let’s try and rationalise it.

First, we understand a positive yield to mean that in recompense for locking away some capital, we receive payment in the form of interest from the deposit-taker. A negative yield implies the opposite. That is, we pay the deposit-taker some interest for looking after the capital.

To illustrate and for simplicity, consider a zero coupon, 10-year bond with a face value of $100. That is, depending on the yield, an investor pays an amount today to receive $100 in 10 years’ time, with no other income prior to maturity.

In the case of a positive yield of 1%, the price today of that bond is the present value of the redemption amount, discounted at the yield to maturity of 1%. So $100 payable in 10 years will have a current price of $90.53. That is, $90.53 invested today earning 1% p.a. will accumulate to $100 in 10 years.

If the yield was 0%, then the present value today is simply the $100 redemption amount. And if the yield was minus 1%, then the present value of $100 payable in 10 years will be $110.57.

Present values with negative yields

But what does a present value of $110.57 at minus 1% really mean? It means that to have someone hold $100 for a period of 10 years, we must pay them interest of $10.57 today. That is, interest required for the whole period is charged up front.

Another way to think of this transaction is from the bond issuer’s point of view. To look after $100 for 10 years, they ask for $110.57 today, being what $100 would accumulate to in 10 years, at an implied interest rate of 1%. In effect, the bond issuer requires at the outset, the redemption amount accumulated at a rate approximately equal to the bond yield paid by the investor.

To summarise, with negative yields, the investor pays more today than the amount redeemed at maturity. Which makes sense intuitively if we think that the bond issuer needs more than $100 today, if that amount is going to run down over time at negative market interest rates, and $100 must be paid back in 10 years' time.

The logic also holds for exchange traded bonds that pay regular fixed interest amounts through to maturity, such as the 3% coupon, March 2047 bond highlighted above. In fact, using the accumulation approach for that bond, accumulating the future coupons plus the $100 redemption to March 2047, at an interest rate of 1%, returns a value of $226.60. A good approximation to the price of the bond at a minus 1% yield, of $227.32.

Why does anyone invest at negative rates?

With some $17 trillion of negative yielding bonds now existing worldwide and growing, why would anyone invest in such debt? There are a number of reasons.

1. Scope for capital gains. If interest rates fall even further, bond prices rise.

2. Ride the yield curve. Assume a normal yield curve where the shorter the term, the more negative the yield. With the passage of time and all else being equal, holding a long-term bond will see the yield fall and the price rise. Therefore, capital gains are possible.

3. If deflation is expected. A negative 1% bond yield with negative 2% inflation, implies a positive 1% real return.

4. If liquidity is important. The highly liquid and cash-like bond market is usually preferable to holding a wad of cash.

5. It may be the best yield you can achieve without putting your capital at risk, with government bonds virtually risk-free.

We have a new world order when it comes to investment yields on government debt, and negative 10-year bond yields in Australia may not be too far away here. So we should at least try to make sense of a strange situation and adapt accordingly.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary. This article is gheneral information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.