Introduction

In May this year, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) lowered the official cash rate to 2%. This move ushered in the lowest interest rate environment since 1959 when the money market was established in Australia. People often ask if it is worth investing in fixed income assets with a long horizon, such as annuities and long bond investments. There is a sense that ‘rates will have to rise’ and so people assume that it makes sense to wait.

In practice though, this is not always the case. A range of factors determine interest rates, and the yield curve already reflects expectations of the future. In many cases, even if the rate looks low, not waiting will be the best strategy.

The yield curve

The yield curve is a series of market prices for interest rate-linked securities that have been plotted to create a smooth curve. The securities on the curve range from short-dated deposits to longer maturity bonds. Typically, the curve slopes upwards: it rises, with the longer maturities reflecting the ‘term premium’ that a lender or investor demands for having money tied up for longer.

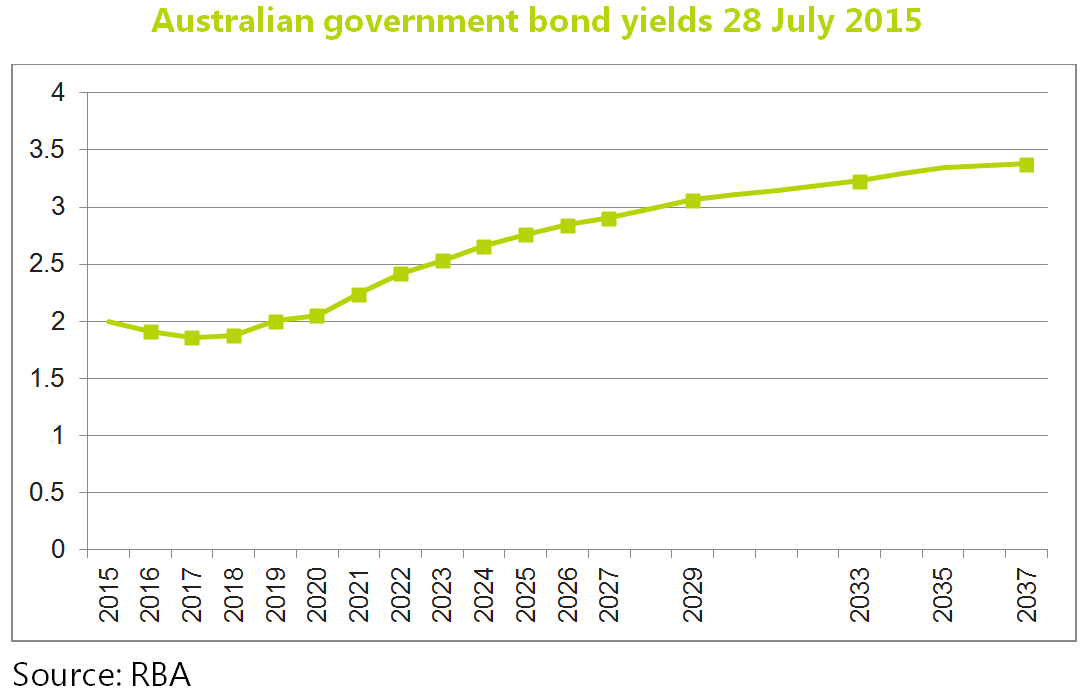

The yield curve is the market’s best view of expected changes to future interest rates. All around the world, highly motivated traders, analysts and investors are making decisions about the likely movements of interest rates for up to 30 years into the future. If those market participants think, for example, that interest rates are going up in 2017, you would already be able to see higher yields in the prices at the relevant part of the yield curve. Let’s have a look at what the current yield curve is saying.

The chart below shows the market forecast for interest rates based on Australian government bonds with maturities out to 2037. The curve initially descends, then is flat for a while, but eventually slopes upwards. What the curve shows is that the market is saying: “We don’t think interest rates are going up before 2017 and they are likely to remain below 4%.”

The role of long dated assets in times of low interest rates

In the accumulation stage, fixed interest assets are used primarily to minimise losses when markets fall. Low returns don’t change the need to manage risk and long-dated assets provide that benefit. Investors in a low rate environment might need to take on more risk, elsewhere in the portfolio, to reach their targets, but the risk-reducing role of bonds remains. Also, low rates will not affect the yield to maturity of a fixed income asset held to term, regardless of what the ‘mark-to-market’ might look like.

In retirement, long dated bonds and annuities are used to generate secure income, not just reduce risk, so the return should matter. Putting aside the option to take more risk, the question is can a retiree generate more secure income by avoiding long dated fixed interest assets?

Is it better to wait?

One of the problems with low rates is that people remember when rates were much higher. What they forget is that interest rates don’t operate in a vacuum. High rates are generally accompanied by other negative factors and externalities, often a breakout of inflation. It would be like remembering that great hot summer from your childhood spent almost entirely at the beach, while forgetting that it was actually a really severe drought. There are great stories about ‘someone’s uncle’ who bought an annuity in the early 1990s when rates were high. In hindsight, that was a great time to buy any long term interest rate-sensitive asset, but many other aspects of the economy at that time were potentially harmful to investors. Government bonds were over 13% and the Reserve Bank was yet to adopt an inflation target of 2-3%. Rates are unlikely to get back to those levels (without an explosion in inflation), but it is tempting to think that waiting until they get to 6% might be a good bet.

The problem with this way of thinking is that you might be waiting a very long time. Japan’s history, for instance, shows us that rate movements are never a one-way bet. Yields continued to fall after the 1989 Nikkei collapse and cash rates have been 1% or lower in Japan for 20 years. The key drivers for low rates have been continuing low inflation (and deflation) and the demographics of an ageing population. The rest of the developed world is facing these conditions now.

Anyone waiting for higher rates can expect higher income down the track. This is exactly what the yield curve tells us. Instead of the 2% rate now, interest rates are expected to go above 4% in the future. But, waiting for interest rates to rise often means you lose out overall; you spend too long holding lower yielding short-term assets like cash and you are trying to ‘time the market’. When rates increase in line with the expectations in the yield curve, the total income payments received are often less than a single longer term investment.

A role for low-yielding assets

The low rate environment is likely to be here for a while. Retirees still need a secure income stream, even if rates are low. Without simply rolling the dice and taking on more risk through investing in more volatile investments, retirees can benefit from buying low-yielding, long-dated assets now, rather than waiting and hoping that rates rise more than the market currently expects.

Aaron Minney is Head of Retirement Income Research at Challenger Limited. This article is for general educational purposes and does not consider the specific needs of any investor.