The idea of a four-day work week is beguiling. Maybe we are feeling burned out or perhaps we are imagining what life could be like if AI does 20% of our work. The promise sounds fabulous: work less, live more and magically get the same or even greater productivity. It sounds like a more balanced, more human future.

Those who champion the four-day work week make a big assumption: namely that people can achieve the same outcomes in around 30 hours that they get currently in around 38 hours. This assumption is necessary because the beguiling big idea behind the four-day work week is that salaries will stay the same.

Advocates often point to trials. A six-month multinational study found that shorter weeks reduced burnout and improved health without impacting performance. A pilot within Australasia saw most participating organisations say that they would adopt the model long-term. The problem is that in a trial, most participants know they are being observed and measured and that carrot-and-stick of “make this work or lose it” is powerful. Whether the productivity gains persist for the long term is still to be seen. Whether they would persist if a four-day week was a permanent entitlement, without the discipline of trial conditions, seems unlikely. And it hasn’t yet been tested in many diverse environments beyond offices with laptops and deadlines.

Many jobs cannot be made more productive while shrinking the hours of work. An ICU nurse cannot work for 4 days instead of 5 and achieve the same levels of patient care. A childcare centre cannot run with 20% fewer staff on a Friday. An essential part of these roles is presence. To reduce hours without reducing service requires more staff.

Despite many trials in the US, a four-day week for school children has had mixed academic results. Student learning declines significantly unless the school day is made much longer (keeping the overall contact hours per week similar). In schooling, like care roles, hours cannot be compressed while hoping for the same outcomes.

And the same goes for construction, retail, hospitality or transport. An hour of labour is exactly that: an hour. By contrast, most high-profile trials of the four-day week have been run in white-collar workplaces, where tasks are more flexible.

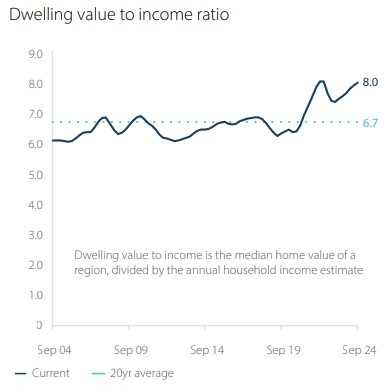

Then there’s money. Many workers could already choose to reduce their hours. Some do, but most don’t. You can’t blame them. Housing affordability in Australia is at its worst levels in history. The national house price-to-income ratio now sits about eight. In Sydney it’s more than 13. The idea that twenty- and thirty-somethings will willingly trade income for leisure is fanciful. Even if productivity gains allowed salaries to remain unchanged on a four-day schedule, the incentive to work five days to save faster for a house deposit would be compelling.

Source: ANZ CoreLogic Housing Affordability Report, Nov 2024. Data: CoreLogic, ANU.

The toughest obstacle may not be structural or economic but our own selves. A century of productivity growth should have freed us to enjoy much shorter weeks already. Our great-grandparents lived on far less real income, often without holidays, cars or early home ownership. Their ‘normal’ would strike us as austere. Yet rather than reducing work, our response to rising productivity has been to choose a higher standard of living. Consumption has expanded to fill our earning capacity.

Rising prosperity is one of the great achievements of modern economies. But it does reveal the tension at the heart of the four-day week. Even if AI delivers us enough economy-wide productivity advances to allow everyone to work four days at the same pay they get now for five days, will we choose that? How long will it be before our lifestyle expectations ratchet up again? Will our grandchildren view space tourism as casually as we view a trip to Bali?

The popularity of the four-day week speaks to a yearning for more balance, rest and humanity in our lives. It’s not a bad idea. But it is an idea whose time has not yet come. Until more people actually choose a shorter week over greater consumption, we should not consider a wholesale restructure of our society, offices and schools.

That day may come. We have seen patterns change throughout history. The idea of a weekend came out of manufacturing early in the twentieth century. The 8-hour day was an innovation as was the 40-hour week. But, for now, the four-day week feels a long way off.

Professor Jenny George is Dean of Melbourne Business School and Co-Dean of the University of Melbourne's Faculty of Business and Economics.