The last 12 months have seen significant upheaval in global markets, with several notable events having a profound impact on the world as we know it. Pandemic restrictions are now in the past as most of the world has decided to ‘live with Omicron’, but we still feel their fallout in the elevated debt burden and fragility of the 'just in time' production model. At the same time, regional conflict has further exacerbated supply chain stresses and led to higher food and energy prices.

Elements of these experiences echo those of the 1970s — another period that started with the aftermath of a severe virus (influenza strain H3N2, ‘Hong Kong flu’) and conflict-induced shocks in the energy complex (Nixon’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War causing a swift and lasting retaliation from OPEC). Some parallels are concrete, whereas others are uncanny. Both pandemics led to the hospitalization of premiers called Johnson, and the series of Apollo missions at the time has now been replaced by a series of missions back to the moon named after Apollo’s sister Artemis.

Investors then, as now, faced the challenge of investing during a period of inflation, cold war, and decoupling, which leaves us with a sense of déjà vu. Yet we are not in precisely the same place.

The current challenge in prices is happening at the same time as a wider sustainability crisis (accelerating physical damages from climate change and biodiversity on the brink). But we are in a better place to find solutions to the crisis, with renewable technologies having gained the critical mass they did not have in the 1970s. Although the respective decades are not in identical situations, distinct parallels can be drawn. Combined with the increased potential for change, these parallels can best be encapsulated by the concept of Déjà New.

The inflation playbook

Inflation has been one of the driving themes and concerns for investors over the past 12 months. Even if many believe inflation is beginning to slow, it is unclear how long it will take to return to a level that resembles central bank targets. Several factors suggest that the challenges of the current inflation bout are far from over and that inflation risk has increased in the long term:

- Globalization is likely slowing and moving toward factionalization.

- Policymakers may be tempted to keep interest rates lower than inflation to reduce the debt burden over time, at the risk of runaway inflation.

- Significant challenges exist with respect to energy infrastructure, security and electrification, particularly in Europe.

- Price increases because of higher wages (the so-called wage-price spiral) could continue, although union power has declined significantly since the 1970s.

- Trends in the pricing of consumer electronics and improvements in storage and processing power appear to have been flattening out, although AI and quantum computing could eventually pull prices down. (The ‘tech deflator’ has been a long-term anchor for inflation.)

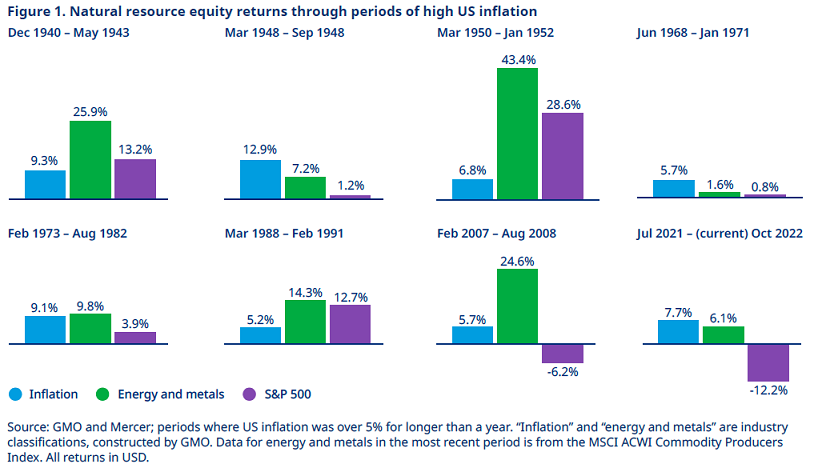

All of this points to the need to structure portfolios for inflation regime management, not just business cycle management, and it is here that elements of the lessons of the 1970s and other periods can be employed. The shift from building in ‘shock protection’ (in response to short-term price movements) to assets targeting longer-term inflation-sensitive revenues may be a sensible rule of thumb for investors to consider. Natural resource stocks provide such revenues, and — despite the performance of underlying commodities — are still arguably under-loved given underserved global energy and materials demand.

In the 1970s, the issuance of inflation-linked bonds was mainly limited to emerging markets, whereas the UK started issuing index-linked gilts in the 1980s, and the US Treasury started issuing Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) in 1997. With real yields now positive in some major territories despite higher inflation and yield curves priced for inflation to fall back again, inflation-linked bonds may offer better protection than nominal bonds against persistent inflation.

The end of ‘free money’

A consensus is that the era of ‘free money’ and ultra-loose central bank policy is at an end. The US Federal Reserve has acted on its plans to raise interest rates to reduce unacceptably high levels of inflation; indeed, the minutes from its September 2022 meeting emphasize that “the cost of taking too little action to bring down inflation is likely to outweigh the cost of taking too much action.” Similarly, other major central banks have taken firm policy approaches. (the exceptions being China and Japan).

Despite this, even the rate rise in late 2022 leaves rates far below the Taylor Rule — a rule of thumb proposed by Stanford economist John Taylor in 1993 as to where we can expect central bank rates to be given current inflation and unemployment levels. Therefore, more tightening has been priced in across a number of asset classes, with real yields now higher in many cases than nominal yields were a year ago and high-yield debt assets now living up to their name.

With higher rates and cheaper equity and bond valuations, investors might be tempted to think there is a stronger case for the traditional 60/40 portfolio; however, reliance on such a strategy is risky, particularly because equities and bonds may be positively correlated during an inflationary environment. Uncertainty remains, and an important concern now should be the potential for monetary and fiscal policies that grate against each other. On one side, central banks are seeking to rein in inflation, whereas on the other side, governments are fuelling inflation through fiscal expansion, seeking to mitigate real wage crunches, securing electoral support and/or seeking to fund transition-oriented infrastructure build-outs.

Balance of power

The parallels with history — specifically the 1970s — can also be applied to current geopolitical and social dynamics. In 1973, US President Richard Nixon proposed providing military aid to Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The result was an Arab oil embargo that forced the Western world to economize for the subsequent decade. Admittedly, several positive developments came on the back of this, with the birth of many renewable technologies, energy-demand-reduction technologies and supporting policies to address the challenges posed by the embargo. Today, there are similarities to that dynamic, with the Russia–Ukraine conflict impacting supply chains and forcing Western countries to consider much-needed evolutions to energy provision and infrastructure.

Alongside this, we are seeing a move away from globalization toward factionalization, with the current Russia–Ukraine conflict and reactions to it drawing dividing lines between nations and regions. This raises the question of whether we will see future conflicts, with a potential Taiwan conflict already a major concern, while score-settling may spread to other regions as hegemons are preoccupied and overstretched. More broadly, factionalization has implications for the powerful deflationary force that unconstrained globalization has had since the start of the century.

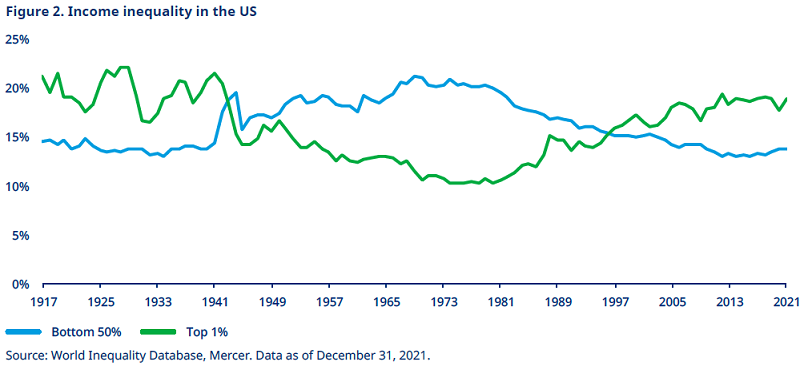

Other threats to the balance of power as we know it are the trends of dissatisfaction and inequality that we’re seeing within society. Inequality is now at pre-World War II levels, with 14% of income flowing to the bottom 50% of society, while 19% goes to the top 1% (see Figure 2).

Global unhappiness (measured by Gallup’s Negative Experience Index) has also been on the rise. These levels of dissatisfaction are potentially related to polarization over economic and cultural issues. At best, this polarization can increase the risk of unconstructive politics or novice governments and, at worst, increase the risk of internal and/or external conflict. With little immediate prospect of these trends reversing, investors should be prepared for more volatility, driven by political and geopolitical events and more uncertainty in general.

This is an extract from Mercer’s paper, “Themes and Opportunities 2023: Déjà New, from hindsight to foresight”. Download the full report or listen to the podcast to learn more about the three key themes which we believe will better position investors for success in 2023 and beyond.

This content is for institutional investors and information purposes only. It does not contain investment, financial, legal, tax or any other advice and should not be relied upon for this purpose. The materials are not tailored to your particular personal and/or financial position. If you require advice based on your specific circumstances, you should contact a professional adviser.