As we enter 2023, I approach the task of previewing economic and financial developments with more than the usual trepidation.

In the first place, we may not be in uncharted waters but certainly unusual currents: high and stubborn inflation, rising interest rates and near constant warnings of imminent recession. The latter has been on the radar of the market commentariat for some time. That is understandable, but at the same time there is little evidence that a substantial economic activity dislocation is in the offing.

A second observation is that I’m not sure the lessons of both recent (post-pandemic) history and lessons of decades past (the high and persistent inflation of the 1970s) have been properly digested by markets and some central banks, including the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

In terms of the post-pandemic period there is an enduring narrative that current inflation – while a little stubborn – is a temporary phenomenon reflecting pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions and outsized increases in the prices of a few selected commodities (largely, but not solely, energy related) that were given further impetus by the Ukraine conflict.

Under this construct, central banks have, after varying degrees of prevarication, met the inflation challenge. Policy rate adjustments from here on in, including in Australia, will be modest, if they are needed at all. Inflation will decline smoothly through 2023 and the big challenge for central banks will be avoiding recession rather than a focus on inflation.

Given that circumstance, the US 10-year bond yield is probably range-bound around a mid-point close to 4% and arguably offers investors an attractive yield without the prospect of significant capital losses.

That might be good news for US equity markets, representing as it does the abatement of what has been a significant valuation headwind. However, while equities benefit from stabilising bond yields, the question remains whether earnings estimates have appropriately priced the cyclical downside. Depending on the extent of cyclical downside, equities seem likely to offer at least low single digit returns and perhaps significantly more if any recession is shallow and short-lived.

Why inflation could prove sticky

That scenario is plausible but there are vulnerabilities and limitations to the logic of that narrative that investors should heed.

For one thing, there seems little appreciation of where monetary policy has come from. The pandemic saw monetary policy assume unprecedented levels of accommodation. Viewed through that lens, policy adjustments through 2022 may have represented a return to some version of normality and perhaps (the US aside) significantly tighter conditions are required to meet the inflation challenge, including in Australia. In the US, policy rate increases through 2023 may be modest but any reversal may take a little more time than markets currently contemplate.

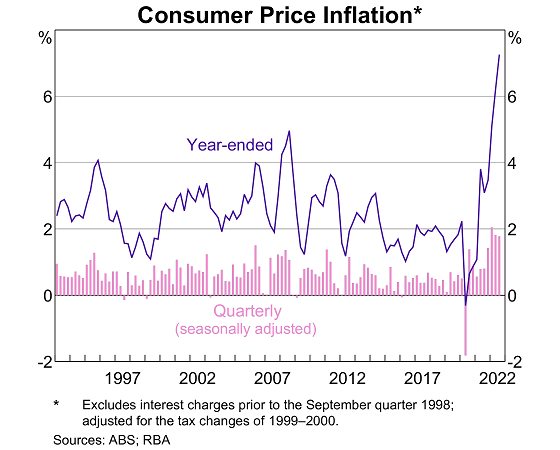

Second, the prevailing narrative on inflation fails to recognise that inflation tailwinds are more pervasive than the consensus commentary might have it. While measures of the US inflation pulse are showing meaningful deceleration, the big question regarding future inflation is over the trajectory of services inflation. It reflects the ‘stickiness’ in services inflation that Federal Reserve officials are reluctant to eschew the option of further tightening – to declare ‘mission accomplished’ – even if positive US inflation portents are clear. Elsewhere, including in Australia, the inflation picture is less encouraging.

The supply-side inflation narrative also downplays the reversal of structural currents that account for the deflationary tendency of the past three decades: globalisation of labour supply (after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the ‘export’ of labour from large emerging market economies such as China and India) and peak baby boomer workforce participation. Other factors such as de-globalisation and re-regulation are also relevant.

In short, the disinflationary narrative and the assumed financial market consequence is a very US-centric one.

The RBA may be wrong again

Locally, the RBA finished 2022 with its hard-won reputation battered and bruised by a ham-fisted approach to policy and the communication thereof through 2021 and into 2022.

Of course, the missteps in RBA communication, including the “no increase in the policy rate before 2024” have been well documented. However, it is more important to recognise that the substantive error that led to that flawed policy communication was an underappreciation of the persistence and magnitude of inflation.

There appears some risk that the RBA continues to underappreciate current inflation pressures. In my view, domestic interest rate markets may similarly underestimate inflation momentum and the policy rate implications.

Some of the RBA caution reflects a belief in ‘Australian exceptionalism’: the notion that Australia’s wage and inflation circumstances are somehow less challenging than elsewhere in the developed country complex. The evidence for such ‘exceptionalism’ is scant.

Indeed, well-intentioned but fundamentally flawed changes to the regulatory environment, particularly in relation to the wage-setting framework, run the risk of entrenching higher inflation in Australia compared to elsewhere.

High frequency data such as the NAB monthly business survey continue to indicate considerable wage and price momentum into 2023. That shouldn’t surprise: the unemployment rate is at its lowest in almost 50 years.

The RBA has defended its comparative caution by warning against “scorching the earth” to get inflation down, implying a more aggressive approach involves outsized costs in terms of activity and employment.

But drawing on the 1970s experience, an alternative construct is that that the ‘scorched earth’ more likely comes from central banks exhibiting some prevarication in assuming an aggressive role in containing inflation and then having to slam the monetary brakes later in the piece.

The key risk with the RBA approach is that it admits the possibility of the emergence of the sort of inflation inertia that was last experienced on a global scale in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

As the RBA Governor has noted, the path to returning inflation to the 2-3% target and keeping the economy on an even keel “is a narrow one.”

Even so, it will be closely monitoring wage and price developments and should be possessed of an acute inflation anxiety as it approaches 2023.

Local interest rate markets should well heed that anxiety. In my view the domestic commentariat and market pricing of the policy rate reflect some complacency on the inflation front.

Diversification is as important as ever

For investors the key lesson is perhaps an obvious one: diversification. That has a particular poignance given a highly uncertain global economic environment.

The foundation of an investment portfolio should be both equity and bond beta, but they are the foundations only and should not comprise the sole components of a portfolio. Nor should the beta be comprised solely of domestic assets. If the RBA maintains its comparative caution that could be a headwind for the Australian dollar unless and until it reverses course. Domestic bond yields may have greater upside risk if the domestic inflation genie escapes the bottle, perhaps implying greater headwinds to domestic equities, particularly if wage and other costs accelerate sharply.

More poignantly investors should be seeking strategies that are non-correlated with equity and bond beta. This may include inflation-linked bonds, commodity exposure (including a small allocation to gold), long/short equity and bond strategies, macro hedge fund strategies, and ‘stylised’ equity tilts (e.g., defensive equity) to name a few.

The last word is agility, implying a modicum of liquidity. I mentioned at the outset ‘unknown unknowns’. A diversified portfolio is a buffer against that. Agility allows portfolio shifts as information sets are updated.

Stephen Miller is an Investment Strategist with GSFM, a sponsor of Firstlinks. He has previously worked in The Treasury and in the office of the then Treasurer, Paul Keating, from 1983-88. The views expressed are his own and do not consider the circumstances of any investor.

For more papers and articles from GSFM and partners, click here.