If investors cast their eyes back over the last two decades, it’s obvious the stock market’s massive winners and 10-baggers – the likes of Amazon, Google and Afterpay – have always looked overvalued and un-investable based on conventional valuation methods. Many investors wielding traditional valuation tools shunned these stocks and missed out on staggering returns.

When investors value established companies, it is a relatively straightforward exercise guided by market capitalisation and earnings multiples, as well as some subjective elements. But it is much more difficult to value early-stage growth companies. Investors often lack these foundations and are forced to follow a process that looks quite different.

Small cap equity investors, particularly, must frequently value less mature companies with short revenue histories, zero profit, and that require significant external capital for growth. Without years of financial data to rely on, early-stage companies and their investors must employ more creative ways to substitute these inputs.

We are in a period of unprecedented innovation and disruption globally. Exciting new companies are emerging every day. If investors can better understand how to value young, fast-growing companies, they will be much better placed to identify the next 10-bagger.

When DCF doesn’t work

For investors to grasp the challenges in valuing early-stage growth companies, they must first understand the mechanics of Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), a valuation method that all analysts are taught.

A DCF financial model projects the expected cash flows of a business into the future. Those future cash flows are then brought back to a value today by applying a discount rate to adjust for the level of risk and uncertainty faced in achieving those cash flows.

The DCF methodology is relatively easy to implement when investors value mature business that have years of consistent earnings and stable margins. But it is much harder to value a business using DCF when its earnings streams are less predictable, such as in an early-stage, fast-growing company. This can lead to potentially extreme mispricing of equities over time, as the likes of Amazon, Google and Afterpay all appeared overvalued but recorded spectacular growth.

Useless metrics

As with DCF, many of the stock standard valuation metrics such as P/E (price/earnings) or PEG (price/earnings to growth) can be completely useless when analysing immature companies.

Their P/E or PEG ratios can look astronomical, and change wildly, because their current earnings may only be a tiny sliver of their potential earnings when they mature. To achieve scale, these companies are often heavily reinvesting in themselves with high R&D costs. Revenues may grow rapidly, but it could take years to deliver profits.

Why is Afterpay’s ‘value’ so high?

A classic example is Afterpay. “How can it be valued so high when it doesn’t make a profit?” they ask. By ‘valued’ we assume they mean its market capitalisation.

Our answer is simple: Afterpay’s valuation, such as its P/E, is so high because it is deliberately keeping the ‘E’ low to non-existent by reinvesting for future growth. Given Afterpay’s superior offering, and the massive size of its potential markets, we would prefer that the company reinvest and realise that potential, rather than spit out profit today.

At the risk of oversimplifying, you can have revenue growth or you can have profits now, but you can’t have both.

Their Australian business is highly profitable but they are using that excess cash flow to grow and take market share in new geographies, meaning they have little to no profit at a group level. The moment they stop reinvesting for growth to prioritise generating profits, at least in the short to medium term, this would likely represent to us a signal for exiting the business.

The corporate lifecycle

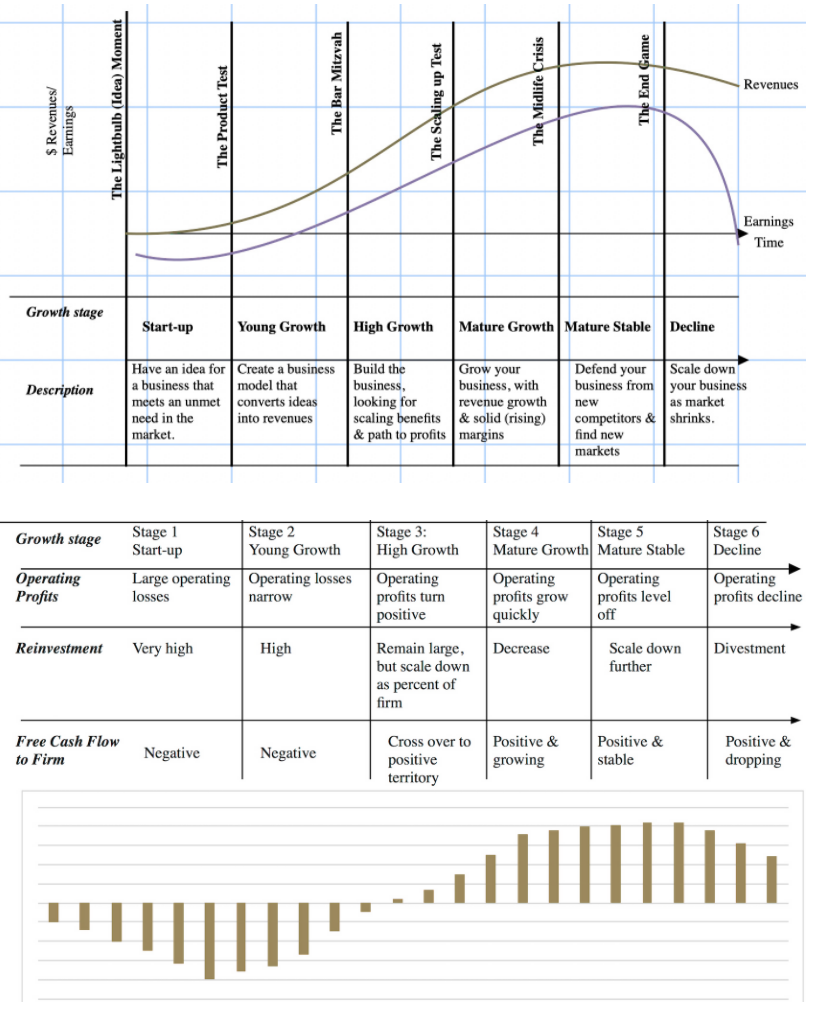

The stylised example below paints a typical picture of a corporate’s lifecycle. Many early-stage growth companies simply don’t have free cash flows that are used to value the worth of a share. So, investors must make assumptions about what these will look like in the future.

Corporate Life and Death – a stylised lifecycle

Source: Aswath Damodaran

Turning to qualitative factors

But how do you make those assumptions?

To evaluate young, high-growth companies, analysts must dive into the underlying business, and judge how long it will take to mature. They will need to refer less to financial ratios and income statements, and more to qualitative factors such as:

- Recurring revenue

- Scalability

- Competitive advantage

- Size of addressable market

- Best-in-class leadership

- Organisational culture

- Track-record of success

- Ability to create new revenue streams

Few of these traits can be meaningfully reflected in spreadsheets.

For legendary investors, such as Peter Lynch, Warren Buffett and Howard Marks, it is the quality of a company’s growth that determines its value, not revenue or even earnings growth per se. When they analyse the broad range of factors outlined above, they can make informed judgements on which businesses are most likely to be long-term successes.

Focusing on four factors

The study of early-stage companies should focus heavily on four key factors:

1. Identifying assets

Usually, the first thing to consider when formulating a valuation for an early-stage company is the balance sheet. List the company’s assets which could include proprietary software, products, cash flow, patents, customers/users or partnerships. Although investors may not be able to precisely determine (outside cash flows) the true market value of most of these assets, this list provides a helpful guide through comparing valuations of other, similarly young businesses.

2. Defining revenue Key Progress Indicators

For many young companies, revenue is initially market validation of their product or service. Sales typically aren’t enough to sustain the company’s growth and allow it to capture its potential market share. Therefore, in addition to (or in place of) revenue, we look to identify the key progress indicators (KPIs) that will help justify the company’s valuation. Some common KPIs include user growth rate (monthly or weekly), customer success rate, referral rate, and daily usage statistics. This exercise can require creativity, especially in the start-up/tech space.

3. Reinvestment assumptions

Value-creating growth only happens when a firm generates a return on capital greater than its cost of capital on its investments. So a key element in determining the quality of growth is assessing how much the firm reinvests to generate its growth. For young companies, reinvestment assumptions are particularly critical, given they allow investors to better estimate future growth in revenues and operating margins.

4. Changing circumstances

Circumstances can move or change quickly for early-stage companies. When a young company achieves significant milestones, such as successfully launching a new product or securing a critical strategic partnership, it can reduce the risk of the business, which in turn can have a big impact on its value. Significant underperformance can also result when competitive or regulatory forces move against a company.

Landing the next 10-bagger

At Ophir, we believe that the market should reward the businesses with the greatest long-term potential premium valuations.

If you avoid early stage growth businesses simply because they have high valuation multiples compared to the market (such as P/Es), you will often miss the most exciting businesses and the next ‘10-bagger’.

That doesn’t mean you should ignore valuation measures, and they are a core part of our process. You can still overpay for high-growth companies.

But when you analyse high-growth early-stage companies, you need to accept that the long-term potential of a business ultimately matters more than its valuation at any given time.

Andrew Mitchell is Director and Senior Portfolio Manager at Ophir Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

Read more articles and papers from Ophir here.